The Scorekeepers of American Medicine

The History of Quality Measures and Why They Persist

“The language of performance measures makes accountability look objective, but it is no less political for that.”

— Theodore Porter, Trust in Numbers: The Pursuit of Objectivity in Science and Public Life

This is the fourth article in the series “Healers to Healthkeepers,” where I trace the history of how America went from building public health infrastructure in the 19th century to making doctors responsible for determinants of health.

In Article 1, “From Sewers to Stethoscopes,” I traced how the Flexner Report bifurcated medicine, separated clinical care from public health, and established physicians as the primary authorities on health.

Article 2, “The Cathedrals of Modern Medicine,” showed how the Hill-Burton Act created our hospital-centric system, with insurance companies as a financial model to finance healthcare.

Article 3, “Everyone is Pre-Sick,” explored how risk factor medicine combined with healthism made individuals morally responsible for their own health outcomes.

Since the public had been primed to take individual responsibility for their own health, it was only a matter of time before payors would demand that doctors collect, track, and act upon risk factors for future disease.

(If you have not read my previous articles on quality measures, one major criticism of this article would be that I link & cite my previous articles, instead of peer-reviewed literature. The reason is that my earlier articles have detailed explanations & extensive links to peer-reviewed literature to the assertions that I make in this article.)

Let’s dive in.

The video version of this article is embedded below and available on my YouTube Channel.

The audio podcast and video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

The Precursors to Modern Measurement

The intellectual origins of healthcare quality measurement began in the 19th and early 20th century, when systematic data collection was first applied to challenge the medical assumptions of that time.1

Florence Nightingale, through her analysis of sanitation conditions and mortality rates among soldiers in the Crimean War, demonstrated the link between environment and health outcomes.

Ignaz Semmelweis’s work on handwashing established a causal relationship between clinical practice and infection rates.

Ernest Amory Codman introduced the concept of the “End Result Idea,” which posited that hospitals had a moral and scientific obligation to track the outcomes of every patient they treated to determine whether the treatment was successful. As co-founder of the American College of Surgeons (ACS), he established the Hospital Standardization Program in 1917, which created the first “minimum standards” for hospitals.

These early efforts were successful and reduced mortality. However, it was Avis Donabedian who proposed the modern quality framework, which is now known as the Donabedian Triad:2

Structure: the context in which care is delivered.

Process encompasses the sum of all activities that constitute healthcare delivery.

Outcome represents the effects of healthcare on the health status of patients and populations.

This framework set in motion the path dependency for quality measurement in healthcare.

Medicare’s Bargain: Coverage in Exchange for Oversight

Whenever someone else is paying the bill, they will eventually demand proof that the money was spent wisely.

The utopian, immanent, and continually frustrated goal of the modern state is to reduce the chaotic, disorderly, constantly changing social reality beneath it to something more closely resembling the administrative grid of its observations.

Seeing Like a State - James C. Scott

When the Social Security Act created Medicare in 1965, it baked in rules to measure cost and quality of care to ensure that tax dollars were spent wisely.

It established the first federal mandates requiring institutions to meet certain standards, such as having credentialed medical staff and providing 24-hour nursing services, to be eligible for Medicare reimbursement. From a “Donabedian perspective,” these requirements fell under the “structure” category of the Donabedian Triad.

In addition to these “structural requirements,” Medicare also attempted, and continues to try, to regulate the cost of care. Below is a brief history of these efforts, the problems with each iteration, and how Medicare continued to innovate in its quest for cost control and quality.

1965: Utilization Review Committees (URCs)

Medicare’s founding law required hospitals to create physician-led committees to review the necessity of admissions and length of stay. In theory, they were also supposed to ensure care met “professionally recognized standards,” but in practice, their role was narrowly focused on utilization.

Problem: URCs were inconsistent, self-policing, and weak on quality.

1972: Professional Standards Review Organizations (PSROs)

To address the URC problems, Congress created regional physician-run organizations to review both the necessity and the quality of care across all Medicare patients.

Problem: PSROs were fragmented, often “captured” by local provider interests, remained inconsistent, and lacked the power to change behavior.

1982: Peer Review Organizations (PROs)

The 1982 reform federalized oversight by contracting with statewide organizations directly accountable to HCFA (Health Care Financing Administration, the precursor to CMS). PROs could deny payment for unnecessary or poor-quality care.

Problem: They earned a reputation as punitive “chart police,” retrospective, and alienating to providers.

2002: Quality Improvement Organizations (QIOs)

In the early 2000s, CMS reframed the program and called them QIOs. These QIOs shifted from punitive review toward collaborative quality improvement, while still investigating complaints and sentinel events. Since 2014, they’ve been split into BFCC-QIOs (beneficiary complaints, appeals)3 and QIN-QIOs (improvement networks).4

In summary, Medicare’s approach has been a pendulum: swinging from increasing accountability over the decades (URC, PSROs, PROs), and when that did not work, to working with providers & supporting quality improvement efforts in medical organizations (QIOs).

QIOs continue to exist today, supporting provider organizations, but when someone else is footing the bill, they will continue to demand that their money is being spent well.

CMS Alphabet Soup: P4P, PQRI, PQRS, MIPS, MACRA & VBC

I covered the history of this “alphabet soup” of quality measurement programs in my previous article, “Value Based Care & The Illusion of Improvement.”

In March 2001, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) released its report: Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. This study grabbed national attention as it highlighted the vast gap in the quality of care Americans received compared to NHS in the United Kingdom.

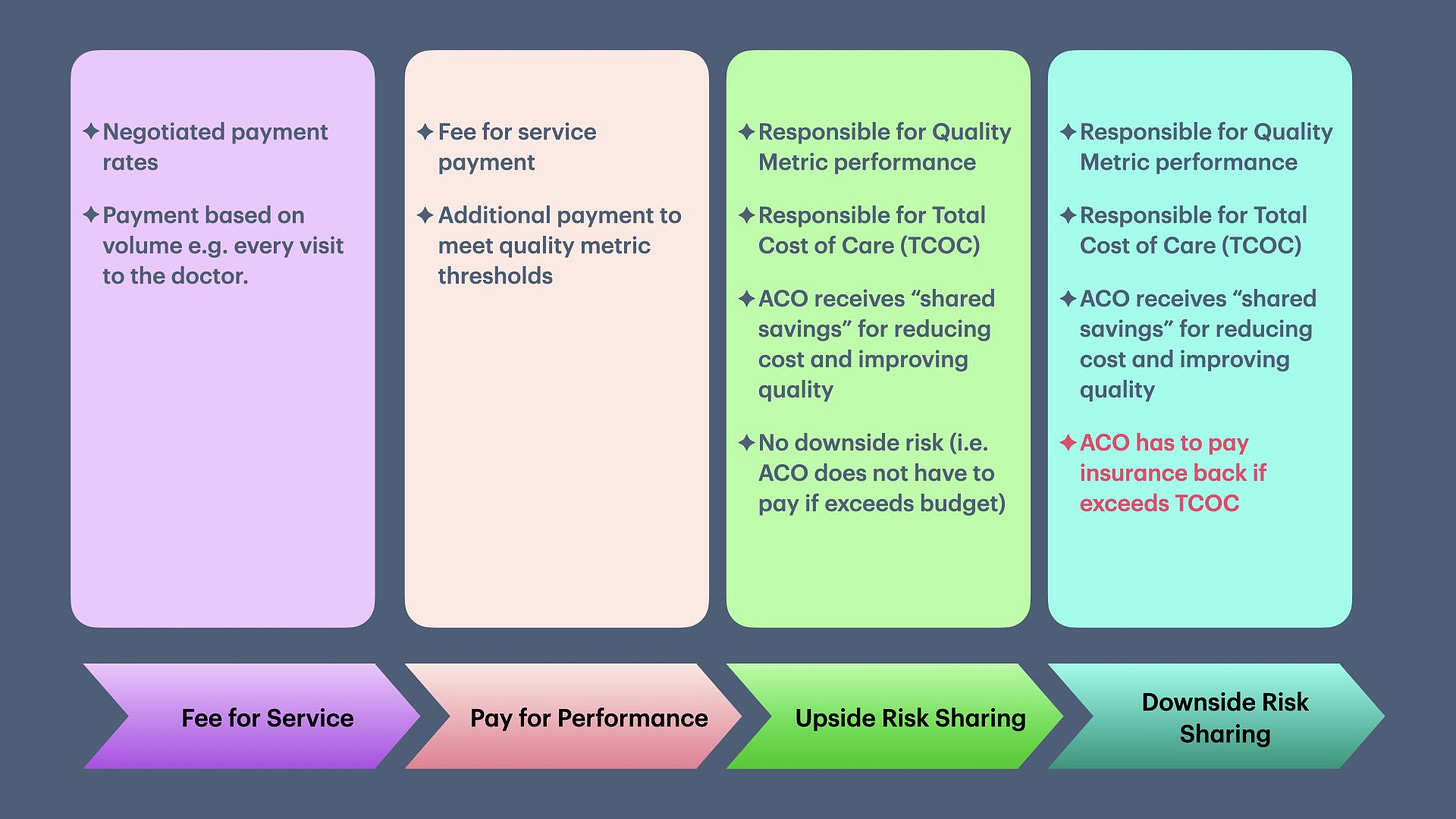

This report led to the rise of the Pay-for-Performance model (P4P), which provides financial incentives to providers, in addition to fee-for-service (FFS), to meet quality thresholds.

The general progression of quality improvement efforts in the 21st century is depicted below:

While Medicare was busy trying to figure out how to keep costs under control and hold doctors responsible, a parallel movement was happening in the private insurance market.

In addition to holding health organizations responsible, CMS also created STAR measures for Medicare Advantage plans when they started becoming popular in 2007. CMS did this ostensibly to ensure that these plans were not skimping on care (i.e., not to repeat HMOs’ mistakes) and to provide transparency to seniors purchasing the plans.

The Ghost of HMOs and Rise of NCQA

I have written about the rise and decline of HMOs in “Value Based Care & The Illusion of Improvement.”

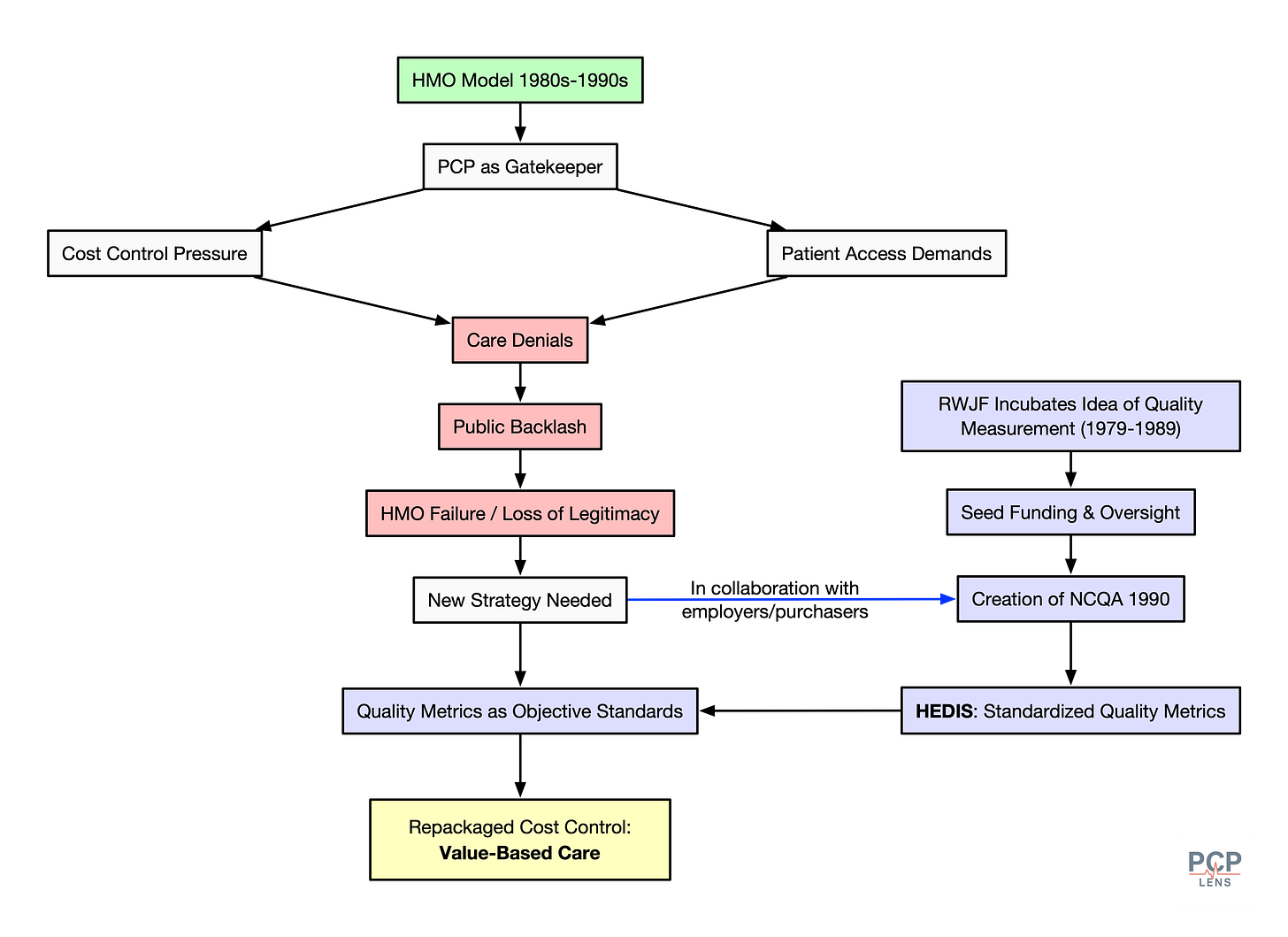

HMOs were designed to control the total cost of care delivered to employees.

…

Over time, as the cost of medical care increased, there was a proliferation of HMO plans, which decreased provider reimbursement (or required providers to deliver more care for the same fees) and reduced the medical care people could receive. These “insurance benefits and carve-outs” eventually became confusing, and people often found themselves without medical coverage. The HMO Act of 1973 aimed to curb several of these abuses by insurance companies by requiring them to cover a more comprehensive set of medical services. HMO plans became more popular after government regulation, but their popularity declined in the 1990s.

As public confidence in HMOs waned in the 1990s, market pressure forced health plans to demonstrate that cost‑cutting didn’t come at the expense of patient care. This credibility gap paved the way for standardized performance measurement. In 1990, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) emerged, creating the widely used HEDIS measures (Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set) to quantify clinical performance. HEDIS allowed employers (aka purchasers) and consumers to compare plans based on quality, in addition to price.

NCQA’s HEDIS measures solved a crucial problem in quality measurement—standardization. If different health plans and medical organizations used different definitions for quality measures, how could purchasers (employers and patients) compare whether two plans were equivalent? HEDIS solved this standardization problem and, in the process, has become a monopoly by creating a strong 2-sided network effect (i.e., health plans have to use it, and purchasers demand it).

Even CMS, which initially defined its own quality measures for the Star Measures, has gradually incorporated HEDIS measures, cementing NCQA’s monopoly status.

As of writing this article, quality measures are everywhere in healthcare. Most health plans, health organizations, and providers are required to track and submit quality measures to avoid penalties or as a precondition to sharing savings in value-based contracts. This is directly the result of America’s 3rd party payment system.

The Rise of Medical Surveillance Machinery

The government’s need for accountability and the private sector’s need for standardized, objective-looking metrics created the perfect conditions for the large-scale data collection apparatus that now defines modern medicine.

The strategy of using quality measures served a dual purpose. It deflected attention from pure cost control by assuring the public that health plans could no longer deny “standards of care.” From now on, these standards would be measured, tracked, and improved to ensure that people would receive appropriate care.

To collect and submit data for quality measures, health organizations have developed a complex system of EHRs, data warehouses, and an army of “data collectors” to find and submit this data manually. Needless to say, these large-scale data collection efforts favor large organizations over small practices. I discussed the details of how this machinery works in my prior article, “The Devilish Details of Data Collection.”

Furthermore, the expansion of these quality measures has done little to improve the actual quality rendered to the population. I understand that this is a strong assertion, but I have written extensively on why quality measurement does not improve outcomes, supported by links to peer-reviewed articles. You can find these articles here.

So, we are left with an ever-increasing surveillance machine that increases the total cost of care while blaming front-line doctors for these costs.

Manufacturing Blame

To understand why this system persists despite its obvious flaws, we need to examine three concepts from political and social theory.

Technocratic Legitimacy

Technocratic legitimacy means delegating authority to experts and technical bodies, to make decisions appear neutral and scientific rather than political.

Quality metrics translate messy debates about what “good care” means into numbers, thresholds, and checklists. Once a benchmark exists, it carries the weight of expert consensus, allowing policymakers and insurers to claim accountability without wading into deeper arguments about equity, equality, resources, or values.

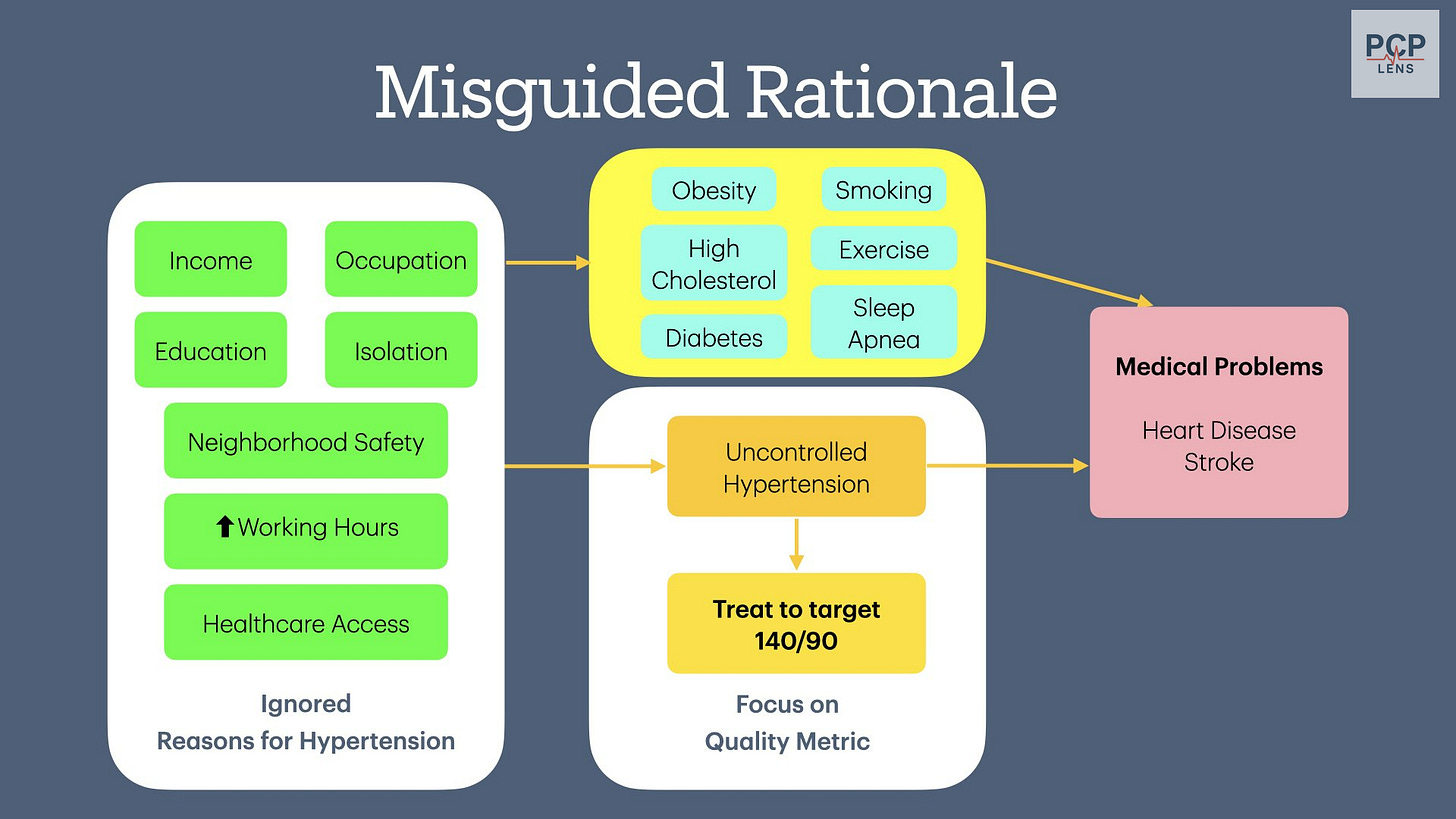

Let’s look at the BP control < 140/90 quality measure. From my earlier article, “The Pressure to Control Blood Pressure:”

The fact that uncontrolled hypertension leads to excess heart attacks and strokes is indisputable. The “powers to be” want you to believe that doctors are not doing their job of controlling blood pressure, and as with any profession, there are a few bad providers.

However, if you look a little deeper, the root cause of uncontrolled hypertension is much more complex and rooted in social determinants of health (SDOH), which we as a country have decided we are not going to pay for.

In the case of the “Controlling Blood Pressure” quality measure, technocratic legitimacy shifts the discussion from the messy political world of addressing the “ignored reasons for hypertension” in the visual above to focus on the technical gap in provider performance!

Discursive Framing

Discursive framing is a technique that uses language to point us toward preferred explanations and solutions, while hiding others. The vocabulary of quality metrics consistently frames structural problems as failures of the individual, either the physician or the patient. For example:

Patient cannot afford insulin —> Medication non-adherence

Chronic stressful environment —> Uncontrolled hypertension, implying the doctor is not managing BP appropriately

Long wait or lack of mental health professionals —> Failure to screen & treat depression

Living in a food desert & unable to afford healthy food —> Uncontrolled BMI, implying doctors are not teaching people about healthy food

Lack of transportation —> Patient non-compliance

(All the links are to my prior articles on these quality measures.)

This linguistic sleight of hand makes physicians responsible for solving the determinants of health, while never naming them as problems. The discourse shapes not just how we talk about healthcare, but how we think about it, measure it, and assign blame for its failures.

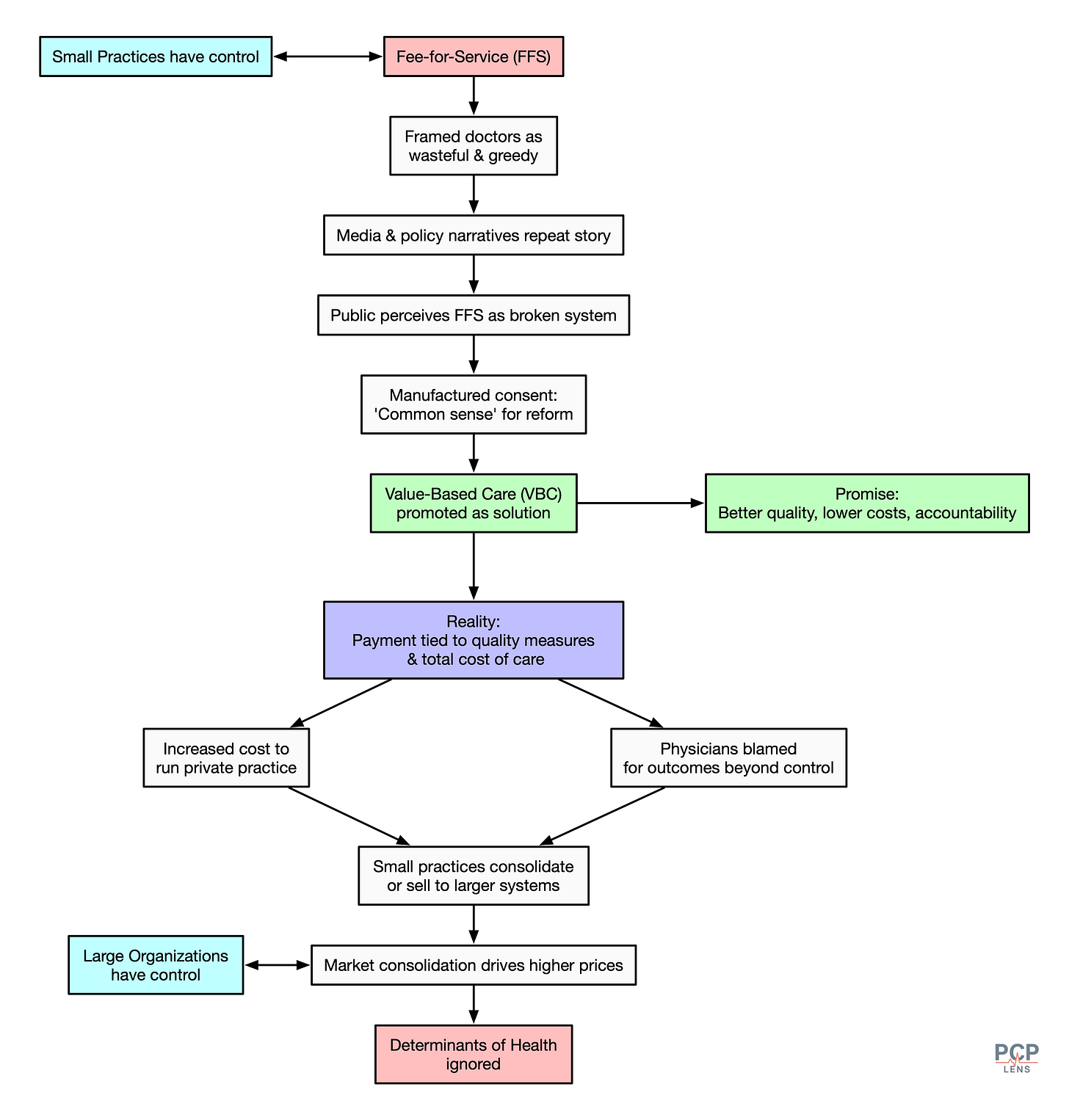

Manufactured Consent

Manufactured consent occurs when media and institutions shape stories so the public agrees with policies that serve the “entities with power.” These policies may or may not align with the public’s interests.

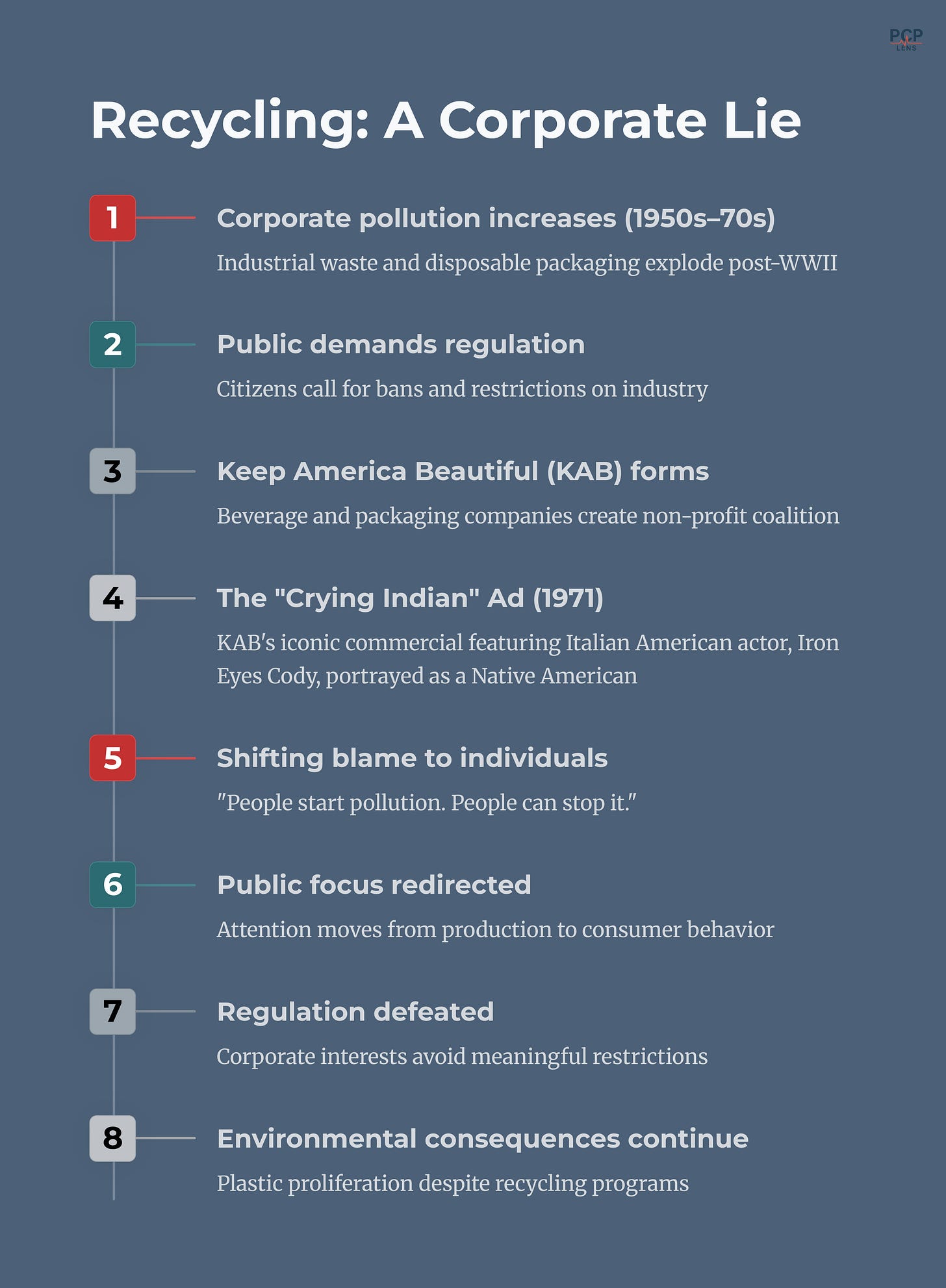

A master class in manufactured consent is the corporate lie that recycling plastic waste reduces pollution.

For decades, media and policy reports have consistently framed the fee-for-service (FFS) payment system as the engine of “waste,” “overutilization,” and “fragmentation,” blaming physicians for driving up costs by doing more to earn more. By repeating the story that FFS rewards greed and inefficiency, institutional narratives made Value-Based Care (VBC) appear as common-sense reform, while masking the reality that both models struggle with the same structural determinants of health.

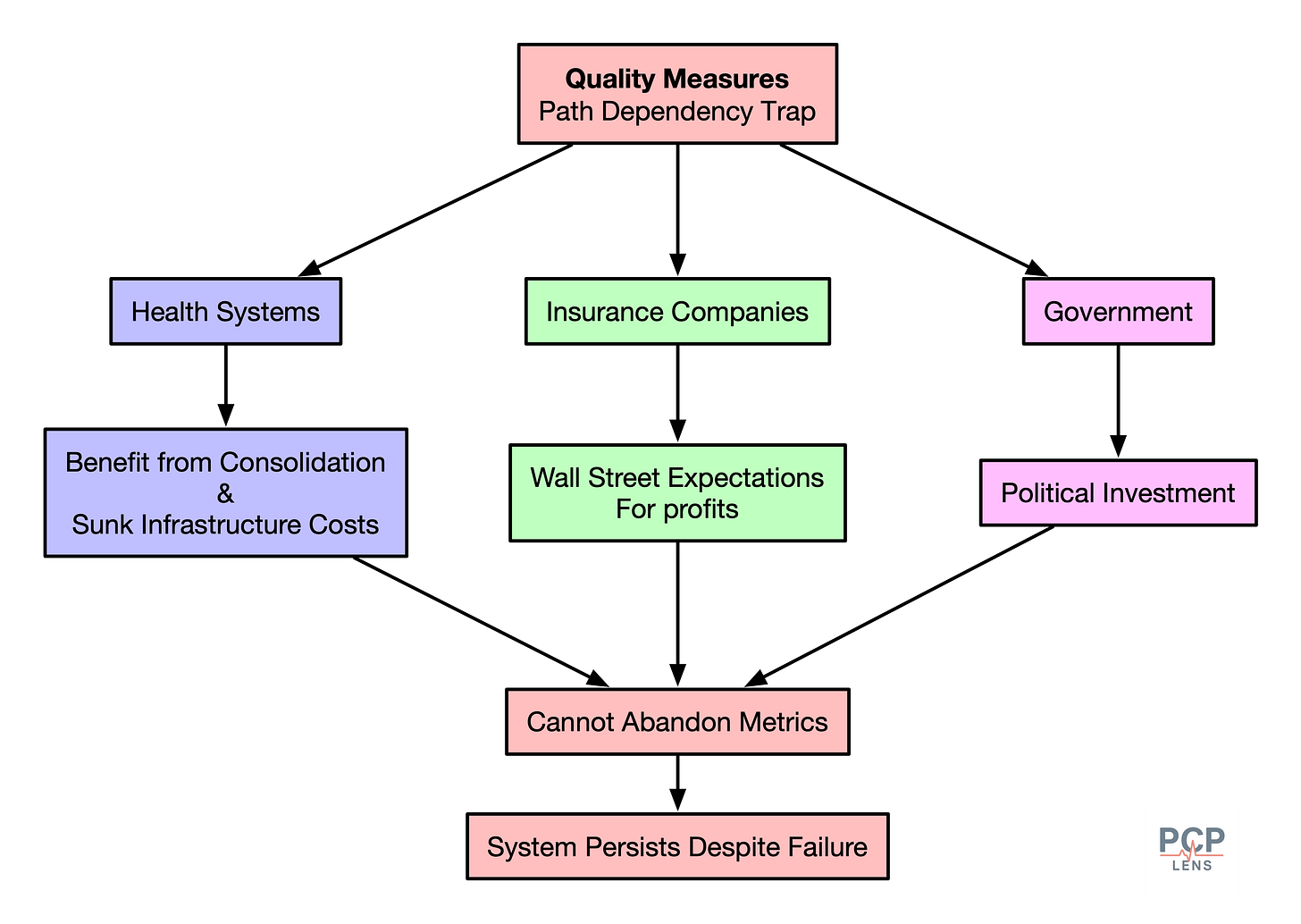

The Path Dependency Trap

The irony of the US healthcare system is that everyone knows the system is broken, but path dependency makes escape nearly impossible.

Insurance companies (especially MA plans) will not abandon metrics without admitting their value-based contracts are financial shell games leading to record profits. They’re now locked in Wall Street expectations to continue to generate these profits.

Health systems have consolidated at the expense of small practices and invested billions in quality reporting infrastructure. This has allowed them to extract higher profits from employers/purchasers. Walking away means not only writing off those investments and admitting that quality measures don’t improve quality.

Government programs like Medicare have staked political capital on quality improvement. Abandoning MIPS/VBC would require Congress to admit that a decade of reforms has failed.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we’ve built a system where:

Insurance companies need to generate higher profits by denying care, gaming risk-based coding, and other games to satisfy Wall Street expectations

Quality measures provide “objective” cover for those denials

Physicians are blamed & demonized for systemic failures

Patients suffer while everyone points fingers

This “metric fixation”5 on quality measurement has led to the belief that quantifying human activities can replace judgment and expertise. Healthcare is not an assembly line, and diseases don’t follow protocols. There are good reasons to create guidelines, to guide care when appropriate, and to discard them based on judgment. But turning guidelines into quality measures makes them rules, and in doing so, redistributes blame from systemic failures to front-line doctors.

Up Next

Once the foundation to measure quality was in place, the next step was to operationalize it. The Annual Physical was the perfect vehicle to operate the machinery for data collection, which is the topic of my next article.

Marjoua, Y., & Bozic, K. J. (2012). Brief history of quality movement in US healthcare. Current Reviews in Musculoskeletal Medicine, 5(4), 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12178-012-9137-8

Donabedian, A. (2005). Evaluating the Quality of Medical Care. The Milbank Quarterly, 83(4), 691–729. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00397.x

I wrote about the Donabedian Triad in the context of why quality measures don’t measure what they set out to measure in “The Quality of Quality Measurement.”

BFCC-QIO = Beneficiary and Family Centered Care–Quality Improvement Organization. They handle oversight and accountability. Essentially, they are the watchdogs for beneficiaries.

QIN-QIO = Quality Innovation Networks-Quality Improvement Organization. They handle improvement and learning. They work with hospitals, nursing homes, and practices to improve outcomes, safety, and population health.

The Tyranny of Metrics | Princeton University Press. (2018, February 6). https://press.princeton.edu/books/hardcover/9780691174952/the-tyranny-of-metrics