The Cathedrals of Modern Medicine

How America Built Hospitals and Neglected Health

In my last article, “From Sewers to Stethoscopes,” we saw how 19th-century engineers built the foundation of public health by improving sanitation and a clean water supply. Despite not being medical professionals or understanding biology, these 19th-century engineers succeeded in improving life expectancy. They did this by improving the infrastructure in which people lived, i.e, the Structural Determinants of Health.

In the decades following the “Great Bifurcation” (the historic split between clinical medicine and public health), the arc of history in the mid-20th century converged to create a perfect storm that changed healthcare forever.

This perfect storm not only changed how healthcare would be delivered and financed in America, but it also shifted our mindset from viewing health as a collective responsibility to viewing it as an individual responsibility.

This is a story of path dependency, capitalism, and the rise of hospital-insurance duopoly in healthcare.

This article is the second in my series of “Healers to Healthkeepers.”

Let's dive in.

The video version of this article is embedded below and available on my YouTube Channel.

The audio podcast and video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

Hospitals: The Cathedrals of Modern Medicine

By the end of World War II, American hospitals were in crisis. Many facilities built in the early 1900s were obsolete. The rapid urbanization and population growth left vast gaps in coverage, especially in rural areas.

At that time, the United States had only ≈3.2 acceptable community-hospital beds per 1,000 people, approximately one-third below what planners called adequate. For patients, this often meant crowded, open wards with poor sanitation, a far cry from the vision of a modern, scientific hospital.

Since the Great Depression had frozen municipal bond markets and wartime priorities soaked up steel, cement, and labor, there were no resources to build hospitals to care for people.1

This created a perfect storm composed of:

Demand for better medical care after the war

The Flexner report, which improved medical education and created a class of scientific physicians who needed a place to practice medicine

The federal government’s capacity for massive infrastructure projects, which were hugely successful during wartime

“We should resolve now that the health of this Nation is a national concern; that financial barriers in the way of attaining health shall be removed; that the health of all its citizens deserves the help of all the Nation.”

— President Harry S. Truman, special message to Congress, Nov 19, 19452

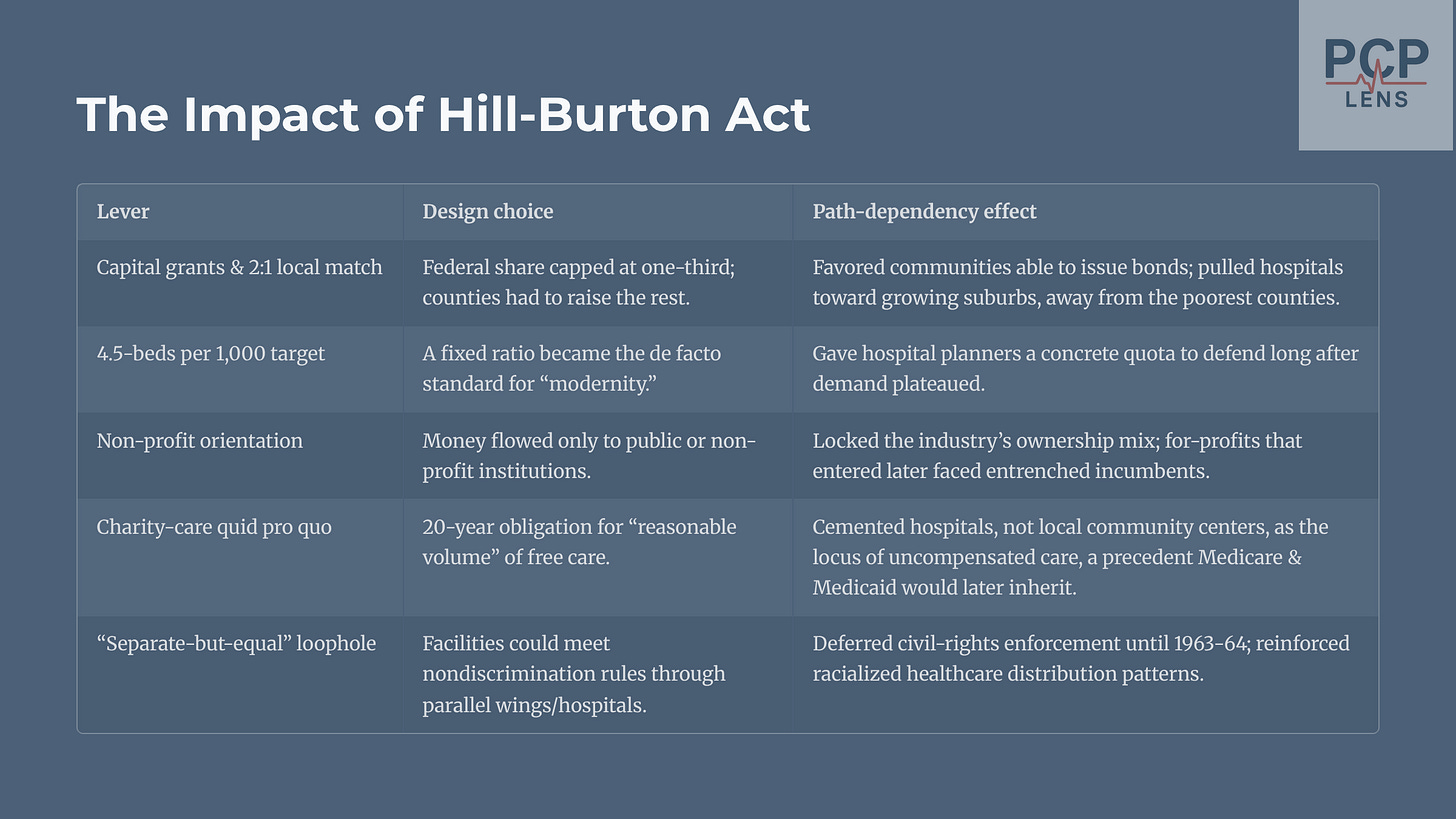

The political landscape led to the passage of the Hill-Burton Act in 1946 to improve healthcare. This act had a deceptively simple formula to fund healthcare, and it put American healthcare on a trajectory that continues to constrain our choices today.3 The table below provides a summary of the act and its path dependency.

By 1975, Hill-Burton money accounted for ≈17 % of all post-war bed growth, adding >70,000 beds and dramatically narrowing rural-urban gaps. More importantly, it set the stage for the rise of insurance companies.

(Per Wikipedia, Hill-Burton assisted in the construction of “nearly 40 % of the beds in the nation’s short-stay general hospitals” during the 1950s-60s.)4

The Birth of Healthcare Insurance

In 1929, at Baylor University in Dallas, Texas, an official named Justin Ford Kimball developed a plan for school teachers. For a prepaid fee of 50 cents a month, the plan guaranteed teachers up to 21 days of care at Baylor University Hospital.

Instead of patients paying for hospital services after they got sick (often with money they didn't have), this system allowed people to pay a small, fixed amount in advance. It was a direct partnership with the hospital to cover the costs of room and board. This arrangement was the blueprint for what would officially become known as Blue Cross. Over the next few decades, these insurance plans started gaining traction.

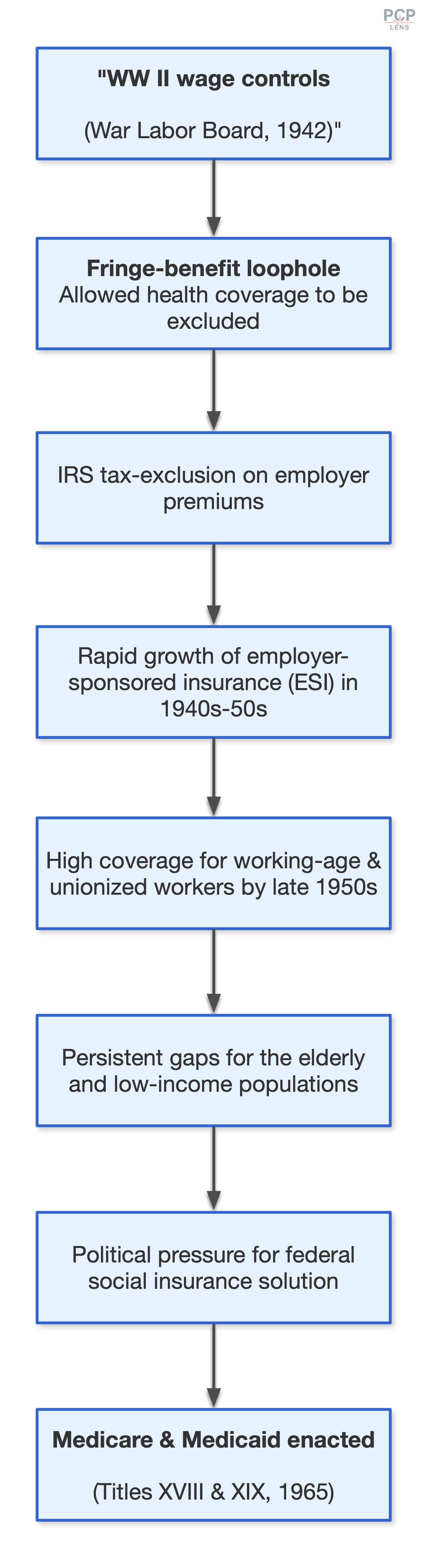

During WW-II, the US government implemented a wage freeze to control inflation and stabilize the wartime economy. Employers who were struggling to attract labor used these health insurance plans as fringe benefits. Over time, these fringe benefits became a standard. The IRS cemented this standard practice into the economy by excluding employer premium payments from taxable income.

As working people were covered by insurance, political pressure gradually built up to extend coverage to the elderly and low-income population. This political pressure led to the birth of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965. This path dependence is demonstrated in the flowchart below.

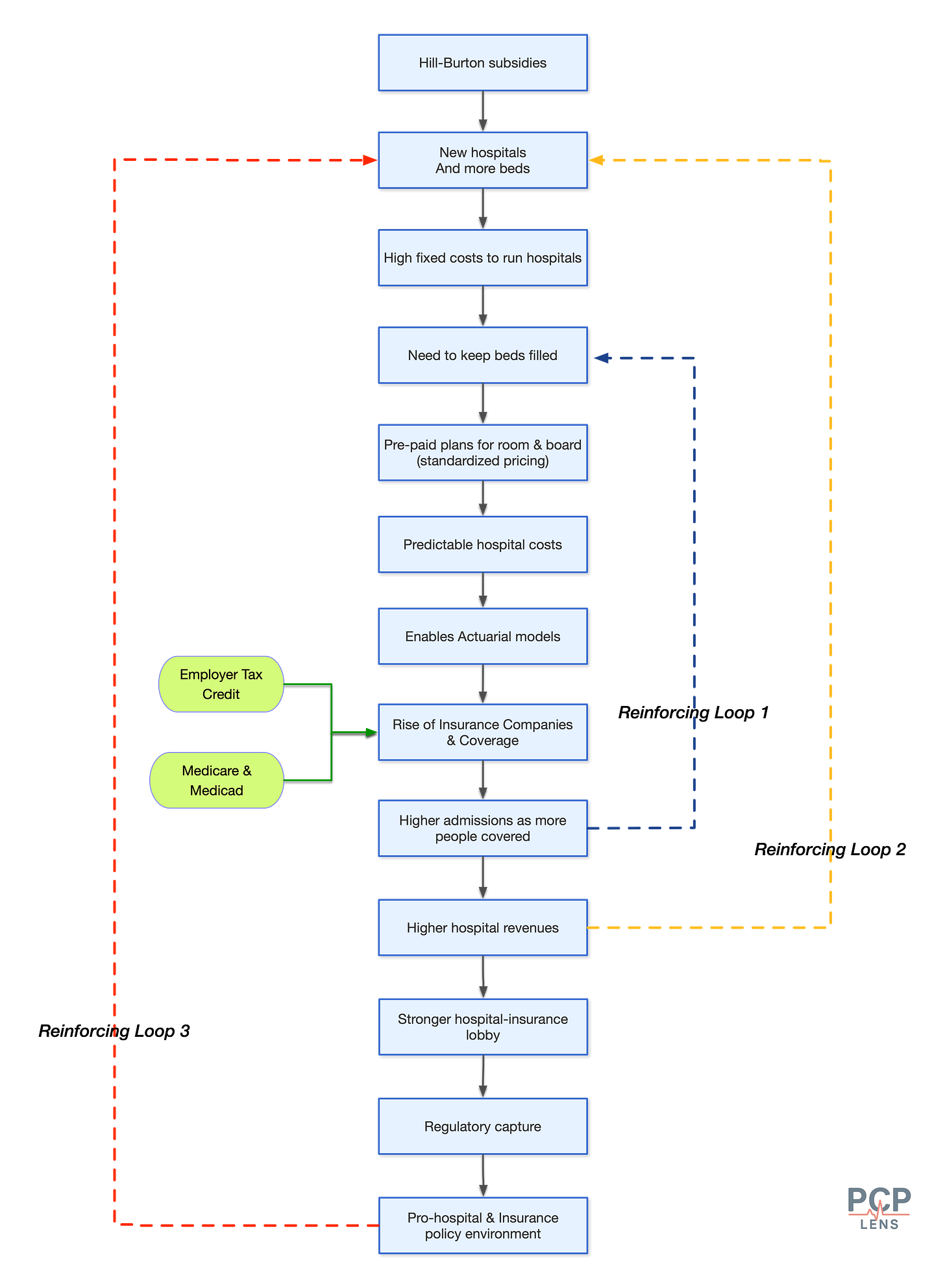

Hill-Burton accelerated the market for health insurance by focusing exclusively on hospital construction and set off at least three self-inforcing loops with increasing returns,5 which is demonstrated in the flowchart below.

Essentially, the Hill-Burton Act’s dramatic expansion of hospitals burdened them with fixed costs (medical staff, utilities, etc). Therefore, to remain solvent/profitable, hospitals now needed a steady stream of customers, aka, patients. To attract patients, many hospitals created pre-paid plans for room, board, and care. Since most hospitals were built to “Hill-Burton standards,” along with the implementation of pre-paid plans, the cost of care delivery became predictable. This allowed actuaries to price the cost of care better and develop insurance products.6

The foundational mistake in the Hill-Burton policy design was tying funds too rigidly to one type of solution (in this case, hospital beds). This made the system blind to a more efficient distribution of healthcare resources.

The Downstream Effects of Hill-Burton

The Hill-Burton Act had far-reaching effects. The path dependency it created had three lock-in effects:

The Institutional Lock-In

Hill-Burton non-profit hospitals became political and economic institutions with their own constituencies as they were often major employer in their regions. This gave hospital administrators significant power and control over local politicians, leading to regulatory capture.

The Financial Lock-In

The debt service7 and operating costs (fixed costs) associated with non-profit hospitals created ongoing financial obligations requiring steady revenue streams. For a long time, financial lock-in made hospitals natural allies of insurance companies and advocates for payment systems that guaranteed revenues.

The Professional Lock-In

Hill-Burton reinforced the Flexner Report’s emphasis on hospital-based medical practice. Physicians trained in Hill-Burton teaching hospitals learned to practice medicine in resource-intensive institutional settings. This training created professional expectations and practice patterns that assumed ready access to hospital facilities and services.

Quick PCP Rant

Today, most PCPs don’t go to hospitals to see their patients who are admitted. Hospital-based physicians, called hospitalists, manage them. However, due to the legacy of this hospital-centric training model, we are still required to be credentialed and on staff at a local hospital.

In day-to-day practice, this means that I have to remain subservient to a local hospital even though I don’t see any patients there.

This requirement to be dependent on a local hospital is due to the path-dependency of physician training and the linking of quality of care with hospital privileges.8

End Rant

The Opportunity Cost

While Hill-Burton poured billions into hospital construction, it simultaneously created an opportunity cost that starved other health interventions of federal attention and resources.

Given that the federal dollars were tied to building hospital beds, it created unintended consequences:

States built, or overallocated hospital beds where they were not needed, e.g., in sparsely populated areas. Outpatient facilities could have better served these places, but there was no economic incentive to build these facilities.

The States built hospital beds where they were able to raise money, i.e., issue bonds. In practice, this meant that hospital beds increased in areas where middle to high-income people lived, even if those areas were sparsely populated.

Since most local funding went to the construction of hospitals, it crowded out funding for outpatient facilities, community health centers, and public health programs.

These unintended consequences, in tandem with the Hill-Burton Act’s “Separate but Equal”9 clause, were magnified in redlined communities that housed mainly poor black and minority communities. These communities were unable to raise money by issuing bonds, so they did not benefit from building hospital capacity. Furthermore, since most of the funds were diverted to build hospitals, there was minimal money left over to construct outpatient medical infrastructure in these communities, creating healthcare deserts.

By 1973, <4 % of Hill-Burton grants had reached public-health centers, a fraction far below the Act’s original intent. GAO’s 1974 audit found that state agencies were “passive in the initiation of projects for the construction or modernization of outpatient facilities, particularly in poverty areas,” and had shifted “substantial” Hill-Burton money out of the outpatient/public-health category to bricks-and-mortar hospitals instead (PDF Link).

Conclusion

In a nutshell, America built hospitals at the expense of outpatient and public health infrastructure. The capitalistic market capitalized on the opportunity to create and sell insurance products, which in turn created an early hospital-insurance duopoly that came to dominate healthcare and regulators.

These changes had profound effects on healthcare delivery. From my prior article, “From Sewers to Stethoscopes,” I wrote about the impact of the Flexner report on American healthcare.

It is a significant historical reason for the paradoxical nature of the American healthcare system: it is home to some of the most technologically advanced medical care in the world, excelling at treating acute, complex diseases, yet it performs remarkably poorly on measures of public health, prevention, and equitable management of chronic illness.

The Hill-Burton Act is the second major, path-dependent reason for this outcome. Having built our healthcare system around these ‘cathedrals of medicine,’ the question we face today is how we can build the community-level infrastructure that was neglected for so long.

At its core, Value-Based Care aims to rebuild community infrastructure to keep people out of hospitals.

Up Next

Now that we understand how hospitals came to be the centers of healthcare delivery, in the next article, I will look at how America transitioned towards making people morally and socially responsible for their own health

Cronin, J. W., Odoroff, M. E., & Abbe, L. M. (1953). Hospital beds in the United States. Public Health Reports, 68(4), 425–433. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/71902

Special Message to the Congress Recommending a Comprehensive Health Program. | The American Presidency Project. (n.d.). Retrieved August 3, 2025, from https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/special-message-the-congress-recommending-comprehensive-health-program

Chung, A. P., Gaynor, M., & Richards-Shubik, S. (2016). Subsidies and structure: The lasting impact of the Hill-Burton program on the hospital industry (NBER Working Paper No. 22037). National Bureau of Economic Research. https://doi.org/10.3386/w22037

Haglund, C. L., & Dowling, W. L. (1993). The hospital. In S. J. Williams & P. R. Torrens (Eds.), Introduction to health services (4th ed., pp. 160-210). Delmar Publishers.

Pierson, P. (2000). Increasing Returns, Path Dependence, and the Study of Politics. American Political Science Review, 94(2), 251–267. https://doi.org/10.2307/2586011

The Blue Cross insurance product was already picking up steam during and just after WW-II. The ability to improve actuarial models due to predictability in hospital care pricing reinforced and expanded the insurance market.

Since Hill-Burton required 2/3 investment by the states, this money was raised by hospitals from local bond markets. This debt needed to be paid back, which made it imperative to generate revenue from hospital admissions.

NCQA guidelines require all physicians to be credentialed at a local hospital. All major health plans then follow these guidelines.

To secure Southern votes, Hill-Burton explicitly permitted segregated (“separate but equal”) hospitals. In practice, this often meant that Black patients were relegated to overcrowded, under-equipped basement wards, even in newly constructed facilities. Per Senator Hill, the political reality at that time was either building segregated hospitals or no hospitals at all for Black and minority communities.