From Sewers to Stethoscopes

How Structural Determinants Collapsed Into the Exam Room

In the mid-1800s, London was drowning in filth. Human waste emptied into the Thames, cholera outbreaks were frequent, and the smell of rotting sewage became so unbearable in Parliament that lawmakers fled the building in what came to be known as The Great Stink of 1858.

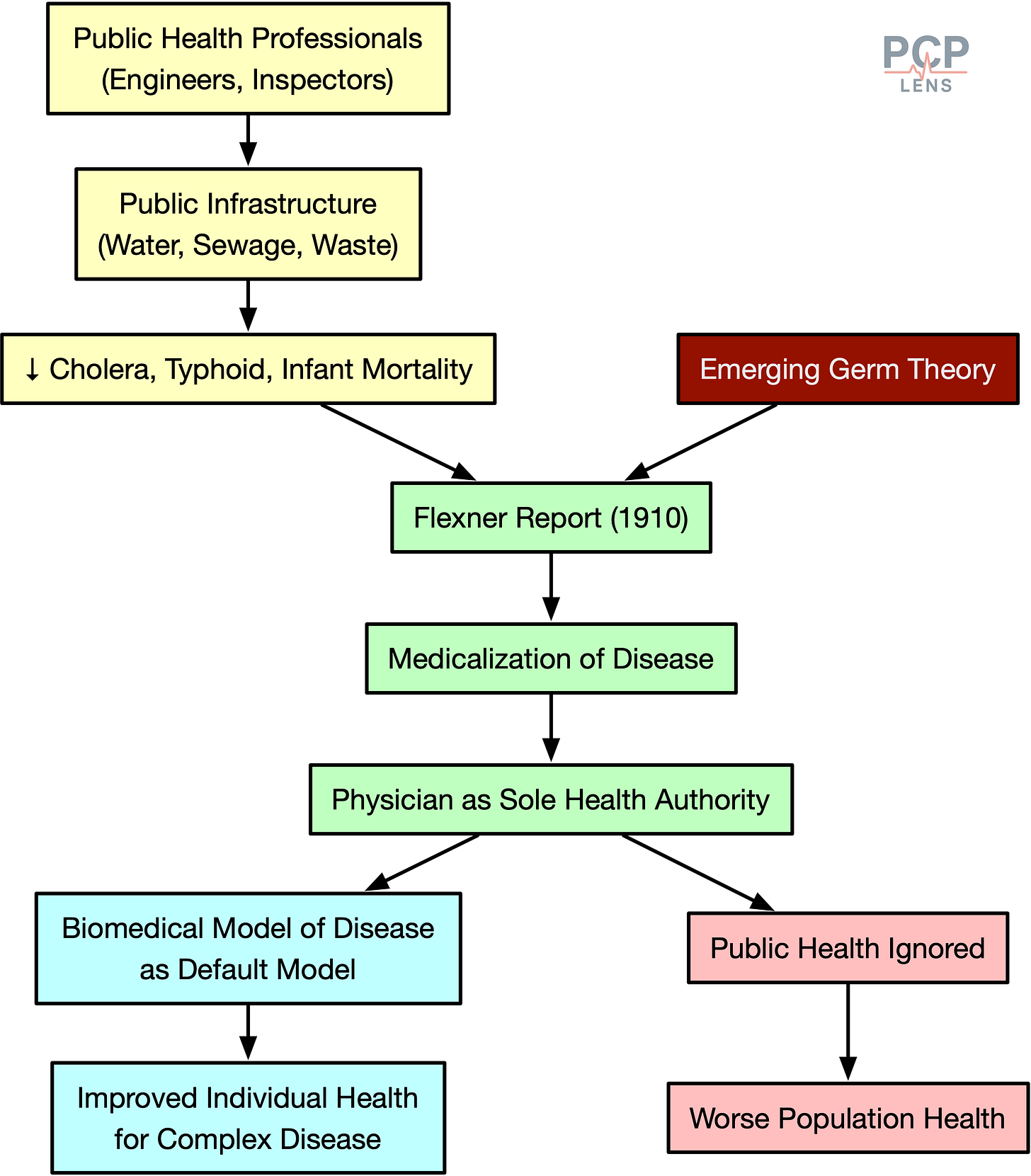

And yet, during this time, before bacteria were even identified as a cause of diseases, before penicillin was invented, life expectancy began to rise. This happened because engineers and sanitation officials built the infrastructure of public health.

So, how did we get from building sewers as health interventions to blood pressure quality metrics in 15-minute visits? This shift, from collective prevention by building public health infrastructure to individual clinical responsibility, is central to understanding why today’s doctors are being blamed, measured, and penalized for outcomes.1

This article is the first in a new series, “Healers to Healthkeepers.” This series explores the history and path dependency that led America from building public health infrastructure to holding doctors accountable, & blaming them for the health of the population.

Let’s dive into the first article.

The video version of this article is embedded below and available on my YouTube Channel.

The audio podcast and video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

The Sanitarian Era: When Engineers Saved More Lives Than Doctors

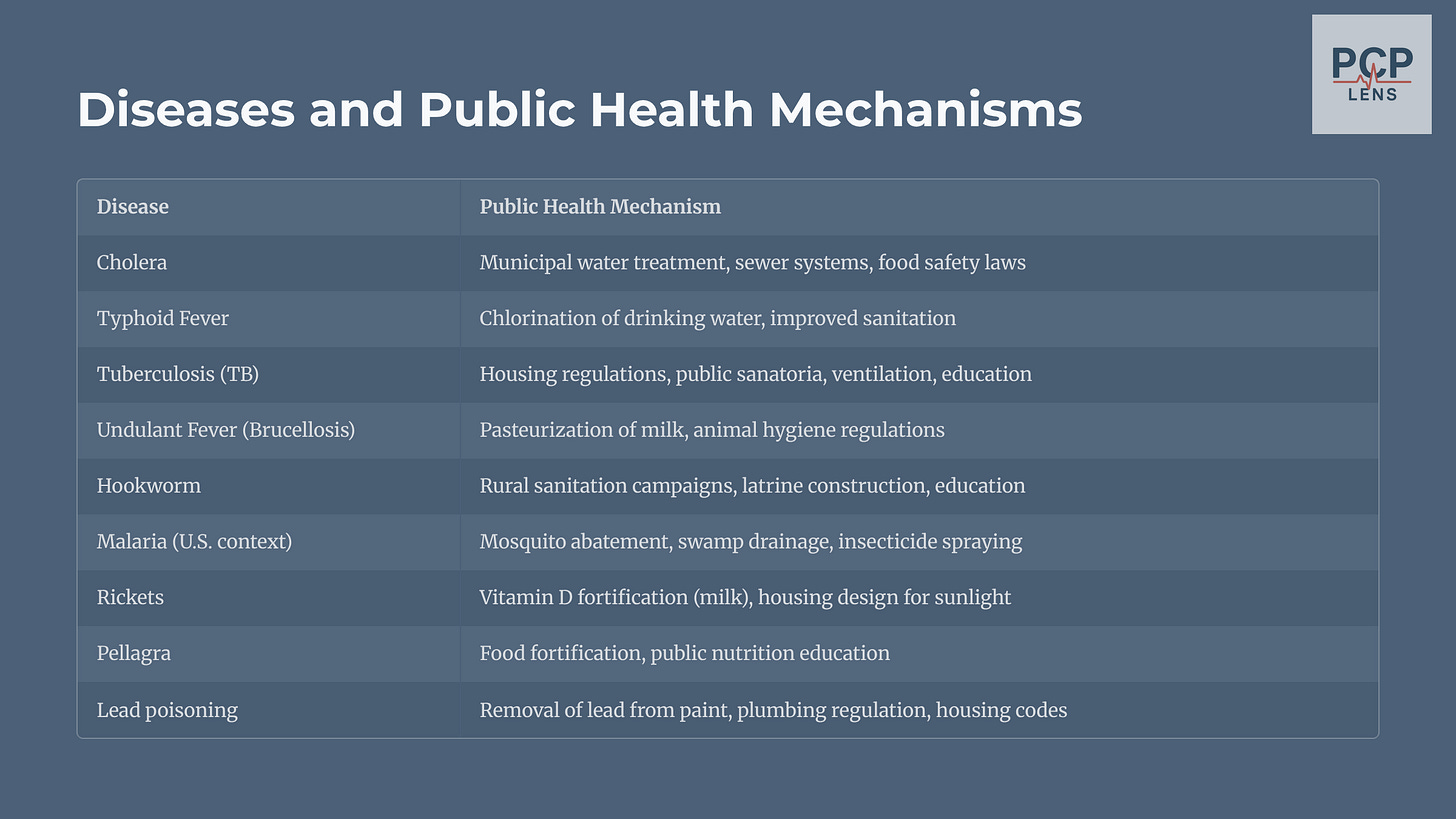

In the 19th century, cities across Europe and North America underwent rapid industrialization, resulting in a massive population shift from the countryside to cities. This urban density overwhelmed the existing infrastructure for housing, water supply, and waste disposal in these cities. This created a fertile breeding ground for disease, leading to endemic diseases such as cholera, typhoid, and tuberculosis.

Edwin Chadwick, a British lawyer and social reformer, authored the 1842 Report on the Sanitary Condition of the Labouring Population of Great Britain,2 which argued:

“All of the most common and dangerous diseases... may almost always be traced to filth, overcrowding, and the absence of drainage and pure water.”

— Chadwick (1842)

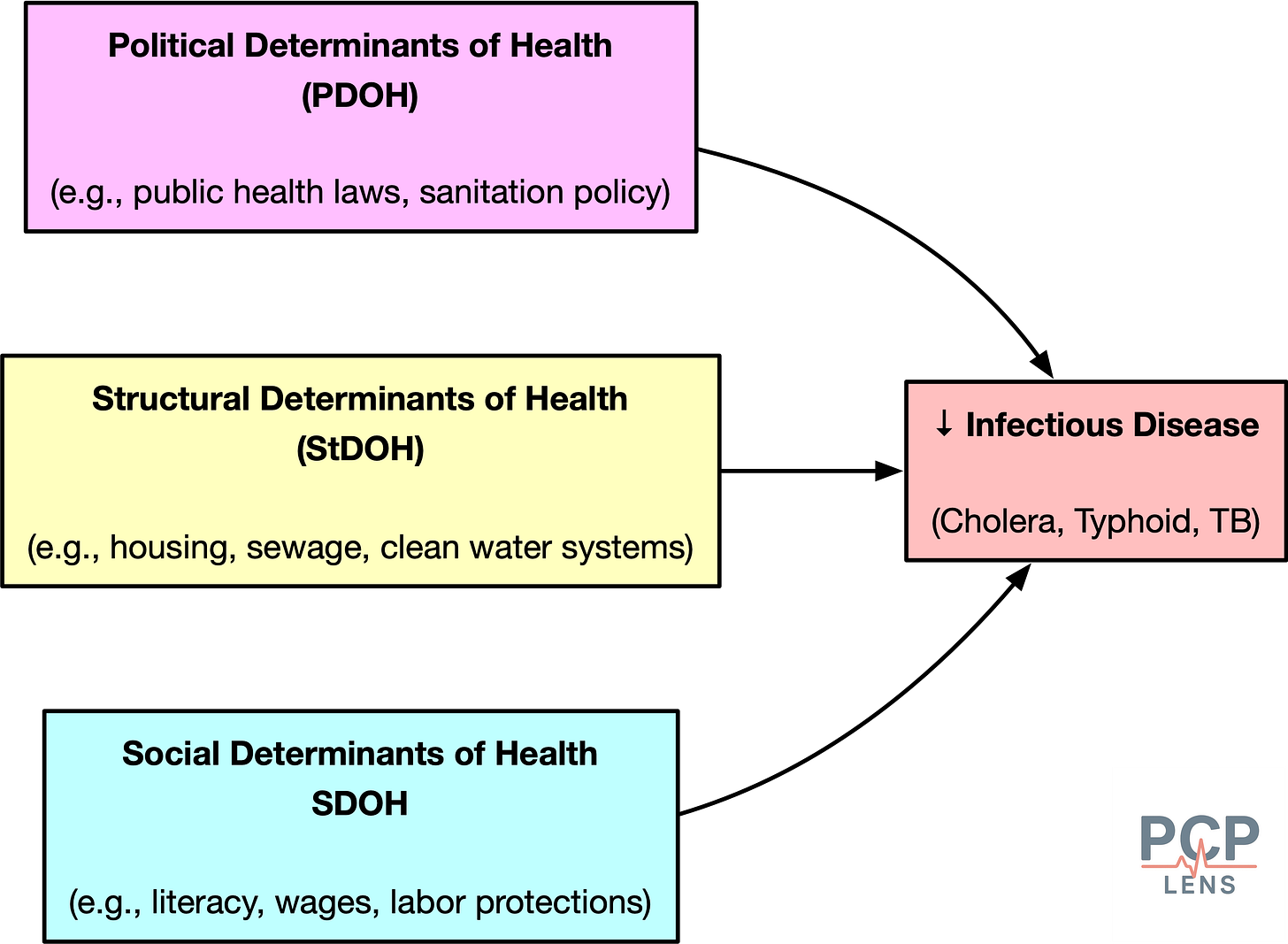

His work launched the sanitary reform movement, which framed health as a civic outcome, and not a moral failing. The focus was not on treating sick individuals with medicines but on re-engineering the urban landscape to prevent disease from occurring in the first place.3 This dominant view led to sweeping public investments in sewers, waterworks, and waste removal across London, New York, Boston, and other cities. These investments resulted in a dramatic reduction in cholera, tuberculosis, and other infectious diseases and led to an increase in life expectancy.

Now, this effort represented a profound assertion of state power and was a political intervention. The implementation of sanitary reforms required governments to intervene in areas of life previously considered private, such as housing conditions and waste disposal, and to appropriate enormous new powers of regulation and taxation.

From Miasma to Microbes: The Birth of Modern Medicine

While sanitary engineers were rebuilding the physical world, a revolution was taking place in the microscopic world. The groundbreaking work of French chemist Louis Pasteur and German physician Robert Koch in the latter half of the 19th century shattered the miasma theory4 and established the Germ Theory of Disease.

This revolution had massive implications:

It shifted causality from the environment to the individual.

It gave doctors and laboratories new epistemic authority.

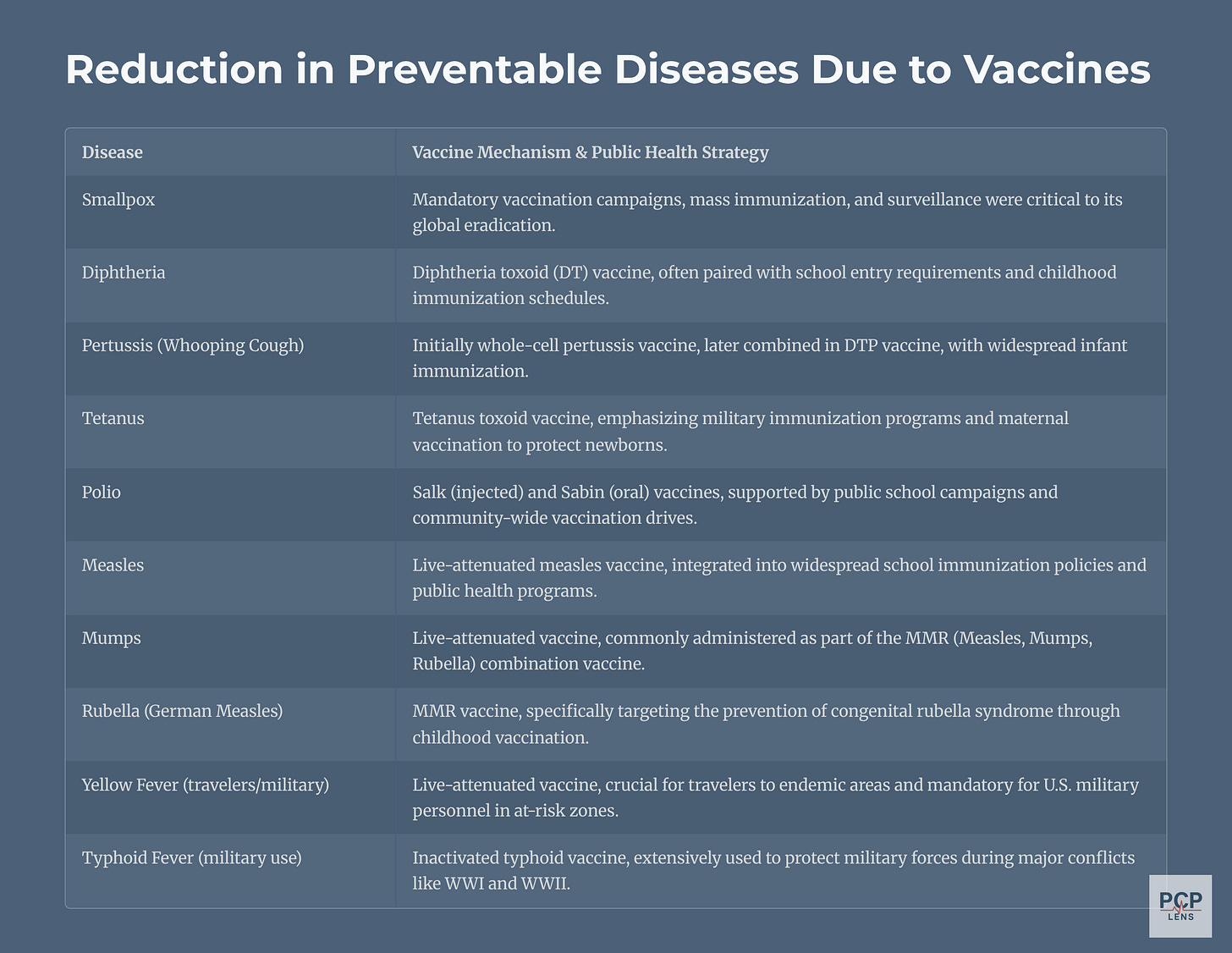

It laid the groundwork for clinical interventions, like vaccination, antisepsis, and antibiotics.

This new scientific understanding shifted the focus of medicine from re-engineering cities to diagnosing and treating the specific pathogen-related disease in individual patients. The Germ Theory of Disease then set the stage for the rise of the “scientific physician.”

The Flexner Report: How Medical Science Took Over Health

In the 19th century, American medical education was an unregulated, chaotic mess. The American Medical Association (AMA), founded in 1847, had long sought to elevate the “doctor” profession by establishing uniform standards. In 1904, it tried to do this by forming the Council of Medical Education (CME) to inspect and rate the medical schools. However, it had no authority to enforce any standards.

As the 20th century began, the American medical education landscape remained deeply fragmented. While elite universities like Johns Hopkins were pioneering a new, rigorous standard based on the German research university model, they were vastly outnumbered by a chaotic marketplace of for-profit schools that required little more than the ability to pay tuition.

In 1910, the Carnegie Foundation published Abraham Flexner’s Medical Education in the United States and Canada (PDF link), a sweeping indictment of substandard, profit-driven medical schools. The Flexner report proposed:

Closing substandard schools.

Require a minimum 2-year college education before medical school admission.

Standardized curriculum (2+2 model = 2 years of basic science with 2 years of hands-on clinical training).

University integration that was staffed with full-time faculty.

The cultural impact of these changes was:

“Medicine is NOT a trade to be learned but a profession to be entered.”

— Flexner (1910)

Backed by AMA and philanthropic organizations such as Rockefeller and Carnegie Foundations, the Flexner Report succeeded in reshaping American medicine.5

While the Flexner report dramatically improved the quality of medical training,6 there were unintended consequences:

Centralized medical legitimacy to elite academic institutions.

Marginalized alternative forms of healing and community-based care.

De-emphasized public health.

As sociologist Paul Starr put it:

“The sovereignty of scientific medicine in the twentieth century rested not on clinical results alone but on control of the cultural authority to define health and illness.”

— Starr (1982, p. 122)7

Physicians emerged from the Flexner era as the professional class most closely associated with “health,” even though the largest health gains still came from improvements in infrastructure, nutrition, and housing.

The Great Bifurcation

The Flexnerian revolution fundamentally altered the landscape of American health by creating a deep and lasting schism between two distinct domains: clinical medicine and public health.

This divided our health system into two specialties:

The physician heroes of biomedical medicine who saved your life when you became sick.

The invisible public health officials who worked tirelessly in the background, trying to keep you healthy.

This specialization initially led to immense progress in both fields. However, it also institutionalized a division in funding, training, and political focus, which over time shifted the focus away from societal health towards individualized medicine.

Furthermore, the Flexnerian medical curriculum, organized around basic sciences, discrete organ systems, and specific disease pathologies, inherently favored medical specialization. Payment reforms later cemented this, rewarding specialists with much higher payments compared to their generalist colleagues (primary care, family medicine, pediatrics).

Specialist training dramatically improved outcomes for complex diseases, but created a paradox. The decline in primary care meant that more patients developed complications, which required specialist treatment that could have been prevented by good primary care.

The Price of Progress

How did the medical profession achieve the power to create such a system?

Paul Starr, in his Pulitzer Prize-winning work, “The Social Transformation of American Medicine,” argues that professions achieve power by establishing authority, which in turn depends on:

Legitimacy: the public’s acceptance of the profession’s claims to superior knowledge and competence

Dependence: the public’s reliance on the profession’s unique skills and services.

Starr further distinguishes Authority as:

Social authority: the power to command and direct action.

Cultural authority: the power to construct reality by defining what is normal and what is deviant (e.g., what is healthy and what is disease).

The rise of the medical profession was a concerted effort to build both forms of authority. This, over time, created the necessary conditions for a phenomenon sociologists call Medicalization: the process by which normal human conditions and social problems come to be defined and treated as medical illnesses.8

And not only do we pay the price for the medicalization of normal behavior (e.g., shyness, grief, pre-diabetes, pre-hypertension, etc), but also a cultural acceptance that healthcare is a contract between an individual patient and doctor, and not a social contract.

This new ideology of individualized health, based on the biomedical concept of disease, led policymakers to neglect upstream factors—housing, wages, zoning—while channeling resources into clinical services.

Conclusion

Now, the above essay is still a simplistic narrative of the complex arc of history and path dependence. For example, it ignores the vast gains in life expectancy from the development of vaccines, which required both the biomedical model to understand the pathogens and public health infrastructure to immunize the population.

Still, looking back, the Flexner model was an exercise in tradeoffs. The historical bifurcation due to the implementation of the Flexner report led to a shift from collective prevention to individual treatment. It is a significant historical reason for the paradoxical nature of the American healthcare system: it is home to some of the most technologically advanced medical care in the world, excelling at treating acute, complex diseases, yet it performs remarkably poorly on measures of public health, prevention, and equitable management of chronic illness.

And to be fair, public health has its blind spots. Some structural determinants of health, especially housing and zoning reforms, are still unequally distributed along racial and socioeconomic lines.

The problem isn’t the bifurcation of medical science into biomedicine and public health. The problem is we let public health infrastructure rot,9 then handed the cleanup to doctors, with no tools, no time, and all the blame.

Up Next

This article laid the foundation for the rise of modern medicine at the expense of public health. In the next article, I will look at how hospitals became the dominant force in healthcare delivery, which in turn led to the emergence of the health insurance industry to finance healthcare delivery.

See my previous articles on “Value-Based Care & the Illusion of Improvement” and “The Quality of Quality Measures” on how doctors are being measured, blamed, and penalized for health outcomes.

Chadwick, E., Great Britain. Home Office, & Great Britain. Poor Law Commissioners (with University of California Libraries). (1843). Report on the sanitary conditions of the labouring population of Great Britain. A supplementary report on the results of a special inquiry into the practice of interment in towns. Made at the request of Her Majesty’s principal secretary of state for the Home department. London, Printed by W. Clowes and sons for H. M. Stationery off. http://archive.org/details/reportonsanitary00chadrich

This was before we even knew that bacteria existed, let alone the development of antibiotics. The only option at that time was probably to reengineer the environment.

Miasma Theory: Bad air or noxious vapors cause disease

Duffy, T. P. (2011). The Flexner Report ― 100 Years Later. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 84(3), 269–276. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3178858/

Flexner’s reforms also improved the quality of care by eliminating snake oil salesmen and unsafe care.

Starr, P. (2017). The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The Rise of a Sovereign Profession and the Making of a Vast Industry. Basic Books.

I discussed the role of disease definitions and their role in healthcare costs in a prior article, “What is a disease?”

And mismanaged it during the COVID-19 pandemic, which has led to a decline in trust in public health agencies.