The Architecture of Illness

A Primer on Structural Determinants of Health

“Medicine is a social science.”

—Rudolf Virchow, linking typhus epidemics to poverty & politics

And,

“The real pre-existing condition in American health isn’t biology—it’s power.”

—My thoughts, rewritten by ChatGPT 4o

In the last 10 to 15 years, we have made significant progress in understanding the social determinants of health, which are defined as the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age. However, SDOH is a manifestation of deeper causes. I discussed 2 of these deeper causes in my last 2 articles:

Chronic Conditions, Corporate Causes - Commercial Determinants of Health (CDOH)

When Policy Fails, Medicine Pays - Political Determinants of Health (PDOH)

In this article, I will look at the societal infrastructure, frameworks, and systems that lay the groundwork for the emergence of SDOH, which then affects health outcomes. These frameworks are referred to as Structural Determinants of Health (StDOH).

The video version of this article is embedded below and available on my YouTube Channel.

The audio podcast and video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

Let’s dive in.

Structural Determinants of Health (StDOH)

WHO Definition1

“the societal, economic, and political mechanisms that generate and maintain social stratification and inequities in society.”

Heller et al., in 20242, proposed a two-part definition of structural determinants of health:

“the written and unwritten rules that create, maintain, or eliminate durable and hierarchical patterns of advantage among socially constructed groups in the conditions that affect health,” and

“The manifestation of power relations in that people and groups with more power based on current social structures work – implicitly and explicitly – to maintain their advantage by reinforcing or modifying these rules.”

If I had to summarize the definition:

StDOH are the power plays of the past; policy choices, both visible and hidden, that still rig the odds today in favor of those already in power.

Relationship between the DOHs

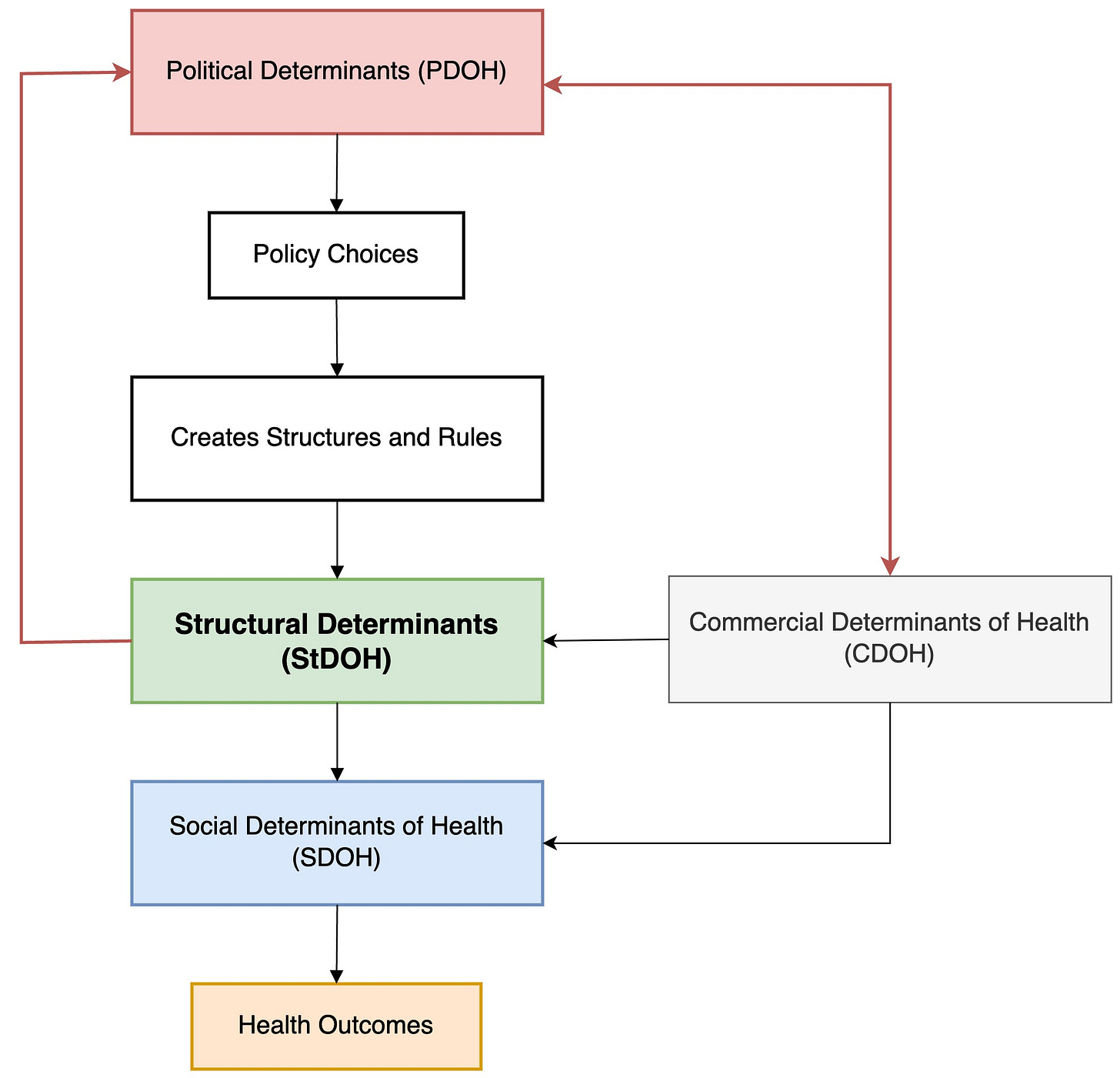

Political, Commercial, Structural, and Social, the determinants of health are interrelated.

PDOH sets the rules through voting, government, and policies.

These rules create, or do not create, infrastructure to distribute opportunities and resources equitably, i.e., StDOH.

These StDOH feed back into policy decisions due to entrenched interests.

This creates the conditions for SDOH to emerge.

CDOH takes advantage of the vulnerable population and, in turn, shapes PDOH to maintain the current structure.3

This relationship is represented in the flowchart below.

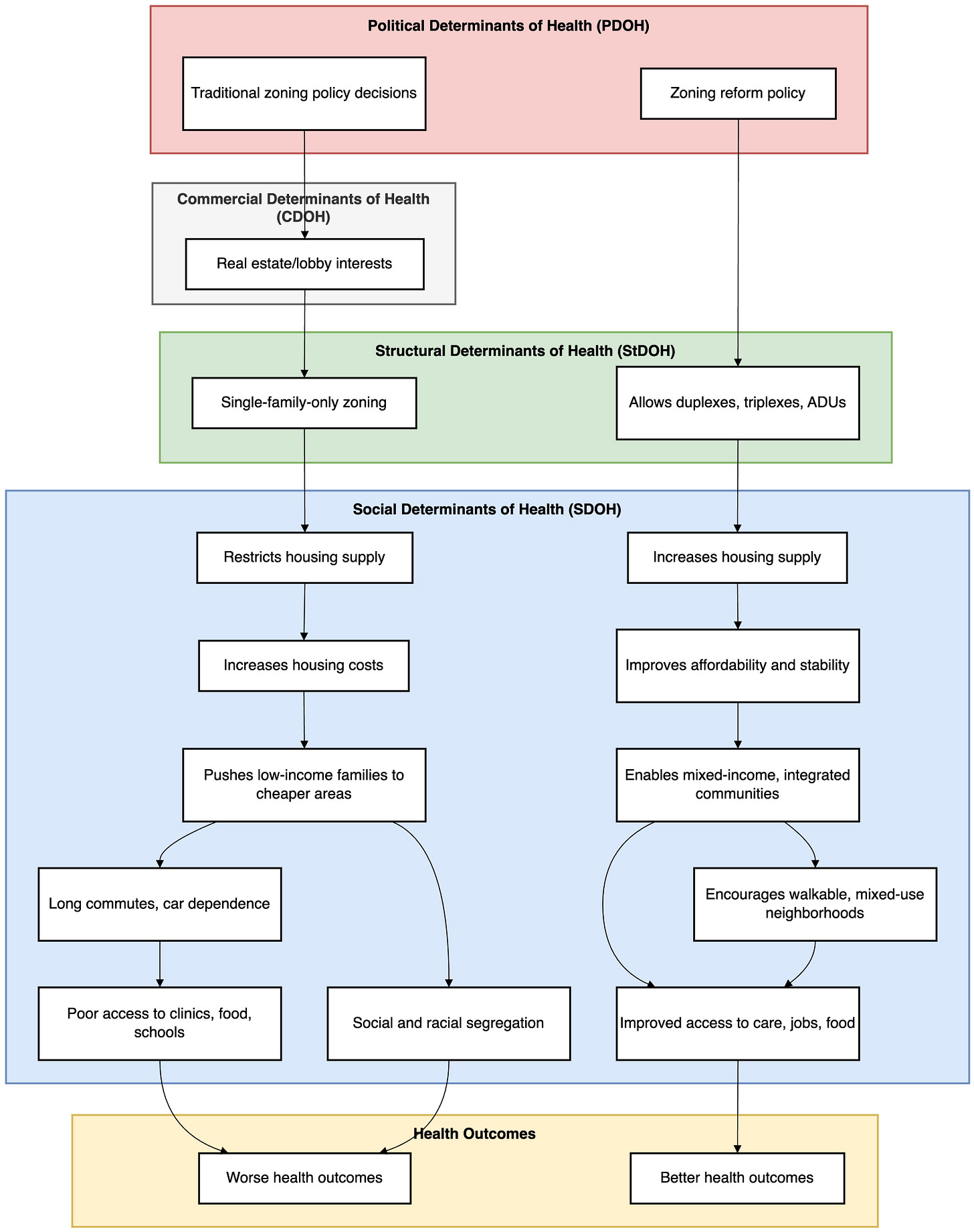

Let us take the example of zoning policies that I discussed in the last article. Policies promoting single-family homes over duplexes and triplexes, which allows mixed-income communities to live together, create the StDOH. This pushes low-income families to areas that are “cheaper” to live in, leading to segregation and poor access to healthy food, aka SDOH. This structure, in turn, leads to poor health outcomes.

Current suburban homeowners, then, don’t allow building affordable mixed-family homes, as that would decrease the price of their house, i.e., they have an entrenched interest in maintaining the status quo.

History and Path Dependence

Francis Fukuyama’s seminal book, “Political Order and Political Decay”4 describes path dependence as:

“Path dependence means that every institution is the way it is because of the way it was in the past. Institutions are often like turtles standing on top of other turtles, which are themselves standing on more turtles, with no solid ground in sight.”

— Francis Fukuyama, Political Order and Political Decay, p. 25

In other words:

The choices of the past constrain the choices of the present

There is enough blood spilled online about the original sin of slavery, and that we should not be beholden to the past by promoting a victim mentality. However, to understand our current situation, it is essential to look at historical events and how our past choices have shaped the society in which we live today.

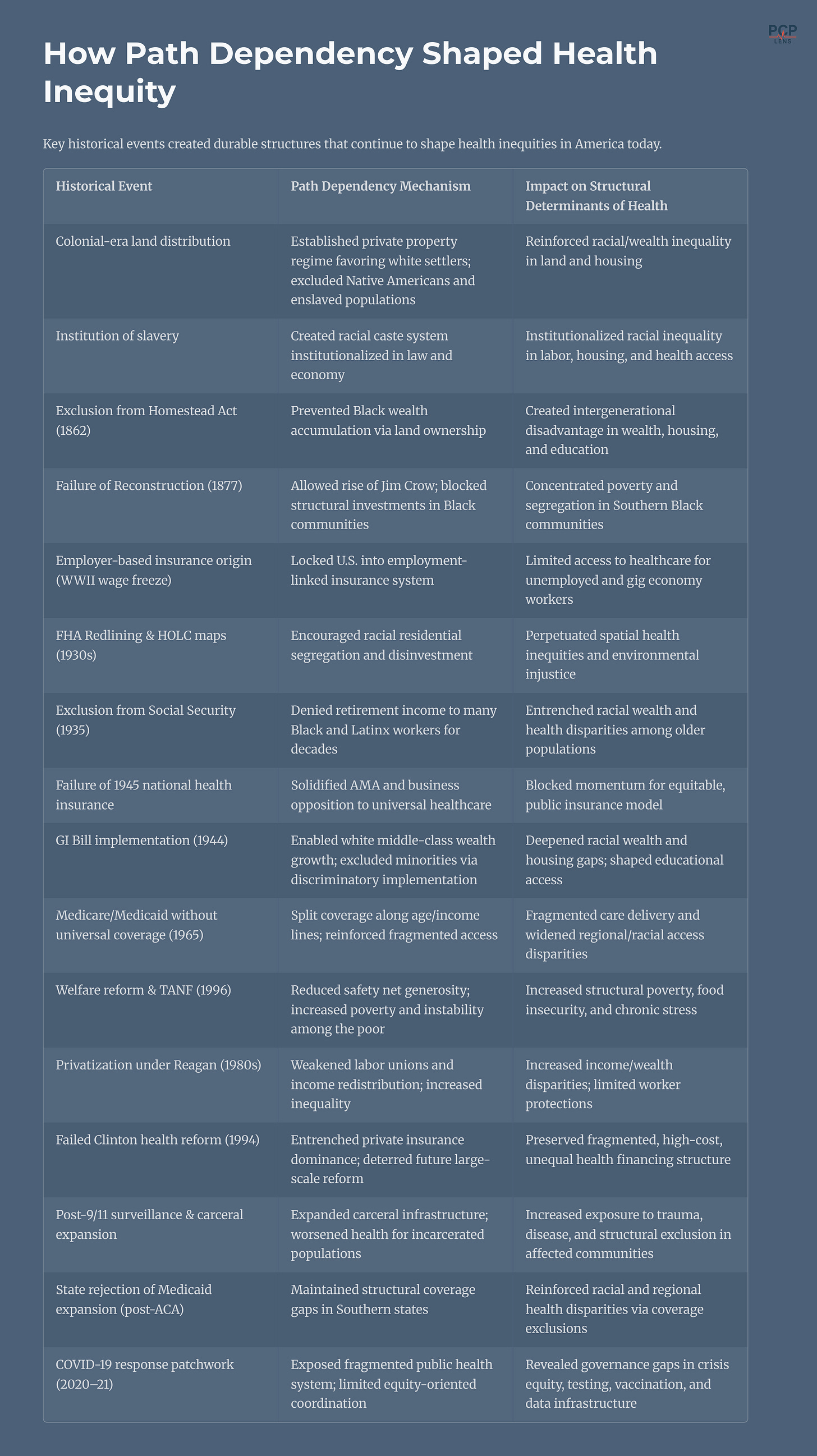

I will leave the details of historical events to the history books, but the table below lists a summary of these events and their impact on StDOH.

While as a country we have made tremendous progress, this progress has been unequally distributed.5 These persistent disparities are the StDOH, which manifests as SDOH.

Putting it together using Housing as an example

You may have noticed that I have mainly used housing to illustrate how Determinants of Health affect outcomes. The reason is that, in my research and opinion, housing is the “anchor determinant,” i.e., it is foundational to the other determinants.6

Let’s apply trace historical origins to the current StDOH, taking housing as an example.

1930s: HOLC Maps & Redlining Begins

The Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) creates maps grading neighborhoods by “risk.” Black, immigrant, and low-income areas are marked in red as “hazardous.”

These designations were explicitly racial and set the groundwork for systemic disinvestment.

FHA Adopts Redlining in Mortgage Lending

The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) refuses to insure mortgages in redlined areas, while subsidizing loans in white, “greenlined” suburbs.

Massive federal investment flows to white neighborhoods; Black and minority families are systematically excluded from homeownership.

Banks and real estate companies actively enforce and profit from redlining, denying loans to Black buyers and steering them into predatory contracts.

Developers and builders lobby for zoning that protects high home values and market exclusivity in white suburbs.

Local Governments Layer on Exclusionary Zoning

Single-family-only zoning and minimum lot sizes are used to keep out lower-income and nonwhite residents, reinforcing the segregated geography.

Affordable multifamily housing is effectively banned in many desirable areas.

Real estate lobbies and homeowner associations pressure politicians to maintain exclusionary zoning for financial gain.

Disinvestment and Decline in Redlined Neighborhoods

Without access to mortgages or public investment, the housing stock deteriorates.

Property values stagnate or fall, draining wealth from communities of color.

Retailers and grocery chains avoid these neighborhoods due to “market risk,” creating food deserts and fewer economic opportunities.

Wealth Accumulation Locked Out

White families build intergenerational wealth through homeownership; Black and minority families are denied this primary wealth-building opportunity.

The racial wealth gap continues to persist or widen over generations.

Persistent Poverty and Segregation

Disinvestment leads to underfunded schools, fewer job opportunities, poor infrastructure, and increased crime.

Neighborhoods remain segregated by race and class, effects that persist for decades.

Commercial Exploitation of Vulnerable Markets

Check-cashing stores, liquor outlets, payday lenders, and unhealthy fast food chains flood disinvested neighborhoods, while banks and supermarkets stay away.

These commercial actors profit from limited consumer options, deepening health and financial harms.

Downstream Health and Social Impacts

Residents of formerly redlined areas experience higher rates of chronic illness, shorter life expectancy, poorer mental health, and less access to care and healthy food.

Persistent poverty, stress, and environmental hazards compound across generations.

Therefore, due to a combination of political action and unchecked capitalism, we created structural barriers, i.e., StDOH. While individual behaviors and cultural factors do play a role in health outcomes, the choices individuals make are themselves heavily constrained or enabled by these structural conditions and opportunities available to them, which make it difficult for people to escape the poverty trap. Some may argue that if people are motivated enough, they can escape this cycle (also known as personal agency), but that does not imply that the system is stacked against them.7

The aim is not to negate individual agency but to understand the unequal contexts in which it operates. For example, if a person does not have stable housing, they will not be able to purchase, store, or cook healthy food. Furthermore, with limited income, their choice may be mainly limited to local low-cost fast food restaurants.

Food for thought:

We often debate that decisions should be local; however, local choices are often path-dependent and may lead to persistent disparities. Why would I want multifamily housing in my neighborhood if my house value decreases?

Path dependency affects countries, local communities, and individuals.

In recognition of these structural barriers, the Minneapolis 2040 Land Use and Built Form aims to redo the zoning policies. The new policies are designed to increase housing choices by developing multi-family housing units and mixed-use neighborhoods.

Power and StDOH

Human history is replete with power plays. Entrenched interests use their power to reinforce or modify rules that benefit them, solidifying their advantage and limiting opportunities for marginalized groups. Reducing inequities involves changing the power structure in society to the benefit of disadvantaged populations. This threatens those in power, pitting the interests of social groups against each other for control of resources. This is the origin of the “us vs. them” mentality.

Without collective action, individuals with fewer resources are structurally disadvantaged, which in turn leads to poorer health outcomes.

Summary

The "us vs. them" mentality in the US, shaped and fueled by historical events (see table above), has led to fragmented and inequitable StDOH. These historical events led to path dependency, which, at critical historical junctures, resulted in failure to act or led to compromises that benefited entrenched powers. This has led to a vicious cycle resulting in significant challenges in addressing StDOH.

This “us vs. them,” which started as race-based inequality, has evolved into a combination of both race and class warfare today.8 The entrenched wealthy elite shape laws to keep their power, promote “us vs. them” divisions, and shift blame onto individuals for problems rooted in a system that protects their wealth.

We mere mortals who have the power to vote buy into this narrative, and often forget:

A rising tide lifts all boats.

And this rising tide applies to both wealth, and health.

Up Next

In the next article, I will look at the interplay between these determinants and how they contribute to a culture of eating junk food.

And, I will attempt to answer the question: Why does McDonald’s thrive in places where grocery stores cannot?

World Health Organization. (2010). A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. 76. https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/44489

Heller, J. C., Givens, M. L., Johnson, S. P., & Kindig, D. A. (2024). Keeping It Political and Powerful: Defining the Structural Determinants of Health. The Milbank Quarterly, 102(2), 351–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12695

Kickbusch, I., Allen, L., & Franz, C. (2016). The commercial determinants of health. The Lancet Global Health, 4(12), e895–e896. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30217-0

Fukuyama, F. (2014). Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, p. 25.

E.g. Since 1968, the Black infant-mortality rate has fallen by two-thirds, and the coverage gap for children has narrowed after CHIP—proof that policy can bend the arc. At the same time, the median Black household still holds only about 15 percent of White household wealth (PDF link), underscoring how entrenched structures blunt those gains.

Krieger, J., & Higgins, D. L. (2002). Housing and Health: Time Again for Public Health Action. American Journal of Public Health, 92(5), 758–768. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.92.5.758

There are examples of community resilience playing a role in overcoming structural barriers, but they are the exception, not the norm.

Race and class overlap yet diverge; Black middle-class homeowners still carry less home equity than equally-paid Whites because of appraisal gaps

Very interesting and thoughtful analysis!