Chronic Conditions, Corporate Causes

A Primer on Commercial Determinants of Health

Four industries—tobacco, unhealthy food, fossil fuel, and alcohol—are responsible for at least a third of global preventable deaths per year.

— The Lancet Commission on Commercial Determinants of Health1

This burden of preventable disease often falls squarely on the shoulders of primary care. What most of us don’t realize is that PCPs are competing with billion-dollar industries that have built their entire business models on addiction and dependence.

Welcome to the Determinants of Health series, or the DOH (pronounced “duh”) series. In this series, I will delve into the upstream factors that make people sick and look at how we have architected the system to shift the blame to doctors.

By the way, if you have not read my other series, I would encourage you to do so. They are linked below.

Moving on to our DOH series.

Commercial industries profit from addiction, pollution, and overconsumption, and are one of the major engines driving chronic disease in the population. These industries shape the food we eat, the air we breathe, and the habits we form. While they rake in billions, the government and health plans hold doctors accountable for rising healthcare costs under value-based care.

In this article, we will discuss the tactics corporations use to drive the consumption of harmful products and manufacture sickness in the population. This new and emerging field of study is called Commercial Determinants of Health (CDOH).

Let’s dive in.

The video version of this article is embedded below and available on my YouTube Channel.

The audio podcast and video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

Defining Commercial Determinants of Health (CDOH)

The field of CDOH is relatively new, and there is no single, widely accepted definition.

The earliest mention and definition of CDOH I could find was by Casswell in 2013. It defines CDOH as “factors that influence health that stem from the profit motive.”2

Since then, organizations like the WHO and The Lancet have proposed several other definitions.

WHO Definition

Commercial determinants of health are the private sector activities that affect people’s health positively or negatively.3

The Lancet Commission Definition

The systems, practices, and pathways through which commercial actors drive health and equity.

Based on the definitions above and our lived experiences, we can all identify commercial activities that negatively impact our health. Let’s look at some of these in detail.

Marketing and Advertising of Unhealthy Products

The most apparent examples of advertising unhealthy products are:

Tobacco products, including e-cigarettes

Alcohol

However, there is an increasing recognition of the role of for-profit companies in designing and marketing highly addictive, processed, and sugary foods. Companies often target these ads towards vulnerable populations, i.e., CDOH targets people with poor SDoH, effectively compounding the harms.4

CDOH targets people with poor SDoH, effectively compounding the harms.

Product Pricing

The commercial industry relies on several strategies to make unhealthy products more accessible and affordable than healthier options. The two that I am aware of are:

Price unhealthy products at a low price, especially by volume (e.g., a large bag of chips or a bottle of soda), or with frequent discounts, to promote addiction and unhealthy habits.

Price healthy (or apparently healthy) products at a higher price, which may be unaffordable for people with lower incomes.

Let’s look at how CDOH creates an environment and culture to push lower-income people to consume sugary drinks.

Companies advertise bottled water as pristine, natural, and purified, linking it to being better for health and a status symbol. This narrative positions it as superior to tap water.5

While rarely making direct, false claims about all tap water (which could lead to legal issues), the industry capitalizes on and amplifies public concerns about tap water quality, e.g., lead in water, the need to boil tap water before drinking, or that tap water has a chlorine taste (which sends the message that tap water is contaminated).

This two-pronged marketing approach, suggesting that tap water is bad and bottled water is good, creates a market for bottled water.

Since bottled water is expensive, soda companies place their products (high-sugar drinks) next to bottled water and price them lower than bottled water.

People with low incomes who have already been primed that tap water is bad and are looking for bottled water are attracted by the low price of sugary drinks and end up purchasing them.

People become addicted to sugary drinks and don’t like the taste of water anymore.

This funnel effectively creates a market structure, driving people away from healthy alternatives, such as free tap water, to unhealthy sugary drinks. This drives up profits for these companies while making people sicker. PCPs are left to battle the sophisticated marketing campaigns that directly undermine dietary advice, making patient education and behavior change almost impossible.

Furthermore, soda companies frame the issue as a matter of individual choice, while actively engineering environments and marketing tactics designed to shape those very choices. The medical-industrial complex responds by assigning responsibility to PCPs through quality measures that mandate BMI documentation and obesity treatment.

Soda companies engineer the illusion of choice—then insist people should be free to choose what they’ve been primed to crave.

This strategic framing of ‘individual choice’ is often protected and amplified through sophisticated corporate influence on policy and regulation, designed to divert attention from their systemic impact on public health.

Corporate Influence on Policy and Regulation

As a strategic tactic, companies often engage in activities that appear beneficial to society or the environment, such as:

Philanthropic endeavors and community engagement initiatives.

Cultivating a favorable public image and building trust with consumers and stakeholders.

Creating a positive association with their brand.

Companies deliberately design these tactics to divert attention from business practices that may harm public health by:

Overshadowing scrutiny of harmful products or practices.

Protecting the company’s reputation and bottom line.

Protecting from potential backlash or regulatory action that may impact profits.

Powerful commercial interests selling products in single-use plastic packaging created the Keep America Beautiful (KAB) non-profit in 1953. They launched it to shift the blame for pollution away from plastic packaging to individuals by framing littering, not plastic production, as the problem. Their narrative promoted recycling as a personal responsibility, distracting from the role of industry in creating the waste in the first place.

By successfully changing the narrative, these companies have avoided regulation while plastic pollution continues to damage public health, and guilt us into recycling.6

Some of you may recognize that these tactics of shifting blame are a combination of:

Lobbying

Corporate Social Responsibility disguised to protect profits.

Focusing on individuals being solely responsible for their health without addressing the systemic corporate drivers of unhealthy choices often plays into the industry’s narrative. These companies avoid regulation, while doctors are blamed and held accountable under Value-Based Care.

Supply Chain & Labor Practices

In the US, supply chains dominated by large food companies often prioritize highly processed, calorie-dense foods over fresh produce. These supply chains make ultra-processed foods cheaper and widely available, which is then heavily marketed, especially in disadvantaged communities, making them more prone to non-communicable diseases such as obesity, diabetes, and heart disease.

For instance, the proliferation of ‘food deserts’ in many urban areas, where fresh produce is scarce but processed snacks are abundant, is a direct consequence of these supply chain priorities, disproportionately affecting communities of color.

The flowchart below shows how these commercial supply chain practices, from ingredient sourcing to labor conditions, can contribute to healthcare costs and health inequities.

Interestingly, these supply chain practices are often reversed in “low & middle-income countries” (LMIC) where fresh fruits and vegetables are often cheaper and more locally available than highly processed foods.

For example, in the US, McDonald’s commonly markets itself as an affordable, convenient option for lower-income and working-class consumers. This is due to an optimized supply chain, which leverages economies of scale and standardized sourcing of low-cost ingredients like beef, chicken, potatoes, and corn. This standardized supply chain enables offering lower-priced menu items targeted at low-income customers.

In many LMICs, McDonald's leverages global brand recognition to compete with local food supply chains and position itself as a premium or aspirational brand. McDonald's prices these products higher relative to local alternatives, attracting more affluent segments of society who view McDonald’s as a status symbol. This is one reason why chronic diseases are more common in the middle to higher-income classes in many developing countries compared to the lower-income class in the US.

Corporate Influence on Research

Corporate influence on research can take multiple forms, including:

Direct funding of studies: e.g., industry-funded research, such as that sponsored by tobacco and alcohol companies, often downplays the harmful effects of these toxins. Drug companies often design sponsored trials to show clinical benefits while downplaying side effects.

Manipulation of outcomes: while not directly funding the research, as benefactors of universities and research organizations, companies can influence research outcomes.

Publication bias: publishing articles that show the desired outcome while withholding research that may negatively impact profits.

Ghostwriting: Drug companies promote their drugs by ghostwriting articles in peer-reviewed literature.

Creating Front Groups: These “independent organizations,” funded by corporate entities (e.g., KAB, Sugar Association), act as spokespersons, promoting industry-friendly narratives and criticizing research that would hamper profits.

Using a combination of these techniques, commercial companies subtly promote their products by funding the creation of articles that are then published under the names of academic researchers in peer-reviewed literature. This tactic is very effective because it leverages the credibility of respected journals and independent researchers to disseminate industry-friendly findings, making it difficult for busy clinicians to discern potential bias.

The tobacco industry’s influence on research is probably best known. What may surprise most people is that the sugar industry’s influence on food policy has had a similar, if not worse, impact on the incidence of non-communicable diseases in the population.

Early research in the 1950s showed the harmful effects of sugar on heart disease. Starting in the 1960s, the Sugar Research Foundation (SRF) routinely published articles in prestigious journals such as the New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM). These articles blamed fat and cholesterol for heart disease.7 The modern version of SRF, the Sugar Association, continues to influence research and public discourse today by deflecting its role in non-communicable diseases and pointing the finger at cholesterol.

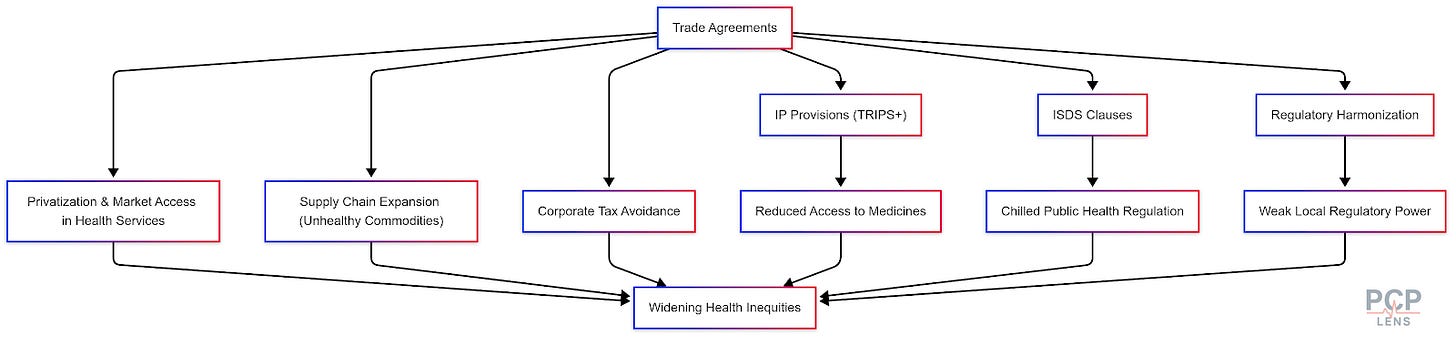

Trade Agreements

Trade agreements significantly impact the CDOH by shaping global market rules that privilege corporate interests over public health goals. This is a complex topic, and it warrants a deeper dive in a separate article (hopefully in the future). The flowchart below gives you a sense of the complexity of global trade agreements affecting healthcare.

If the above flowchart is too obtuse, the flowchart below applies trade policy to insulin.

Conclusion

Parasites don’t kill their host—they keep it just sick enough to feed off. Commercial companies extract as much profit as possible without collapsing the industry, i.e., they effectively function as commercial parasites.

As doctors, we’re handed the downstream consequences of systems built to maximize profit, not well-being. And then we’re measured, blamed, and penalized for failing to reverse decades of structural harm and held accountable for spending too much on the very people these systems made sick.

The greatest challenge to improving health may lie in the tension between wealth and health creation.

Up Next

Now that we’ve explored the commercial playbook, what happens when these corporate forces intersect with the political landscape? In our next article, we will look at the Political Determinants of Health and how they often amplify the health impacts of CDOH.

Gilmore, A. B., Fabbri, A., Baum, F., Bertscher, A., Bondy, K., Chang, H.-J., Demaio, S., Erzse, A., Freudenberg, N., Friel, S., Hofman, K. J., Johns, P., Karim, S. A., Lacy-Nichols, J., Carvalho, C. M. P. de, Marten, R., McKee, M., Petticrew, M., Robertson, L., … Thow, A. M. (2023). Defining and conceptualising the commercial determinants of health. The Lancet, 401(10383), 1194–1213. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00013-2

West, R., & Marteau, T. (2013). Commentary on Casswell (2013): The commercial determinants of health. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 108(4), 686–687. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12118

Commercial determinants of health. (n.d.). Retrieved May 6, 2025, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/commercial-determinants-of-health

de Lacy-Vawdon, C., & Livingstone, C. (2020). Defining the commercial determinants of health: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 1022. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-09126-1

Bottled Water: Pure Drink or Pure Hype? (n.d.). Retrieved May 9, 2025, from https://www.iatp.org/sites/default/files/Bottled_Water_Pure_Drink_or_Pure_Hype.htm

I am not saying we should not recycle, but I am highlighting the success of the KAB campaign. And I recycle as much as possible.

Kearns, C. E., Schmidt, L. A., & Glantz, S. A. (2016). Sugar Industry and Coronary Heart Disease Research: A Historical Analysis of Internal Industry Documents. JAMA Internal Medicine, 176(11), 1680–1685. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.5394