When Policy Fails, Medicine Pays

A Primer on Political Determinants of Health

Of all the forms of inequality, injustice in health is the most shocking and inhumane.

—Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

A hospital closes in rural Appalachia, forcing residents to travel hours to the nearest emergency room.1

A 70-year-old woman has to choose between buying groceries and Eliquis for her newly diagnosed atrial fibrillation.

A single mother juggling between her minimum-paying job and taking care of her kids is disenrolled from Medicaid because she did not file the papers in time to prove she has a job.

These are not merely unfortunate circumstances but the visible symptoms of political choices that have been made, systems that have been built, and policies that have been enacted or neglected. For decades, we have recognized that social determinants significantly impact health outcomes, but we have been slower to acknowledge that these social determinants themselves are shaped by something more fundamental: political decisions. In fact, in my first article, “From Doctors to Social Workers,” I discussed how we distorted the term Population Health from a tool to improve health by enacting policies, to buying and selling the health of a population in the marketplace.

I am talking about Political Determinants of Health (PDOH). In this article, I will look at how policies, both enacted and ignored, affect people, including doctors.

The video version of this article is embedded below and available on my YouTube Channel.

The audio podcast and video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

Let’s dive in.

Defining Political Determinants of Health

Dawes (2020, p. 44) defined the political determinants of health as:2

Involving the systematic process of structuring relationships, distributing resources, and administering power, operating simultaneously in ways that mutually reinforce or influence one another to shape opportunities that either advance health equity or exacerbate health inequities.

There are three major political determinants of health: Voting, Government, and Policy. Voting shapes government decisions, which are then implemented as policy.

Let's look at each of them in detail.

Voting

Voting determines who we elect, and who gets to make decisions that affect health systems, funding priorities, social programs, and regulatory environments. It is the gateway to representation and accountability.

When marginalized populations vote, they can influence decisions on healthcare access, housing, environmental regulation, and more.

When they are disenfranchised by curtailing voting rights (e.g., through strict voter ID laws, limited polling places in minority areas), their needs are often ignored.3

Expanding or limiting access to voting, especially in minority areas, can improve or worsen SDOH.

Government

Government (local, state, national) enacts, enforces, or ignores laws and regulations. It is the operational body that translates votes and policy into action. The priorities of those in power determine how effectively public services are delivered and how responsive institutions are to public health needs.

For example, local governments may enact zoning laws to limit fast-food outlets near schools4 and/or invest in walkable infrastructure, promoting healthier environments.

On the other hand, making it harder for people to get health insurance (e.g., work requirements for Medicaid) will reduce access to healthcare and worsen the health status of people with low income.5

Policy

Policy is the output of political processes, such as laws, regulations, executive orders, and funding decisions. It is how the government’s will is implemented in society and is the most direct mechanism through which health is shaped.

For example, the Clean Air Act (U.S., 1970) significantly reduced air pollution, improving respiratory and cardiovascular health.

Harm from Policy: “Three strikes” sentencing laws in the U.S. contributed to mass incarceration, disproportionately affecting Black communities and leading to long-term physical and mental health harms among incarcerated individuals and their families.6

Connecting the dots

The three determinants, voting, government, and policy, are closely linked. A functional system effectively reflects the population's desires. However, this interconnectedness also means that the system can be disrupted or undermined at any point, causing it to fail.

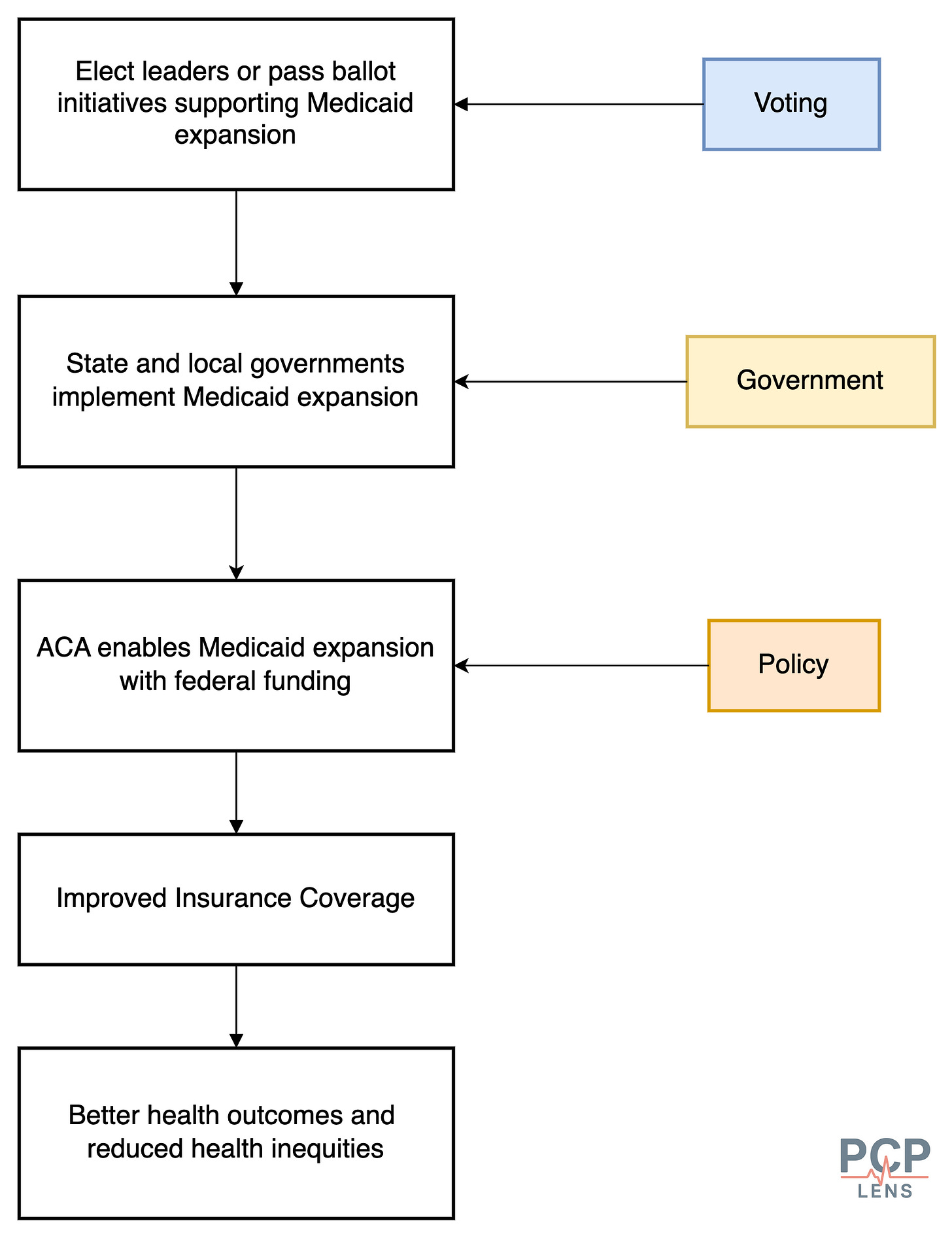

The flowchart below illustrates how a well-functioning system can expand health insurance coverage, especially for minority groups, when they are allowed to participate in the civic process.

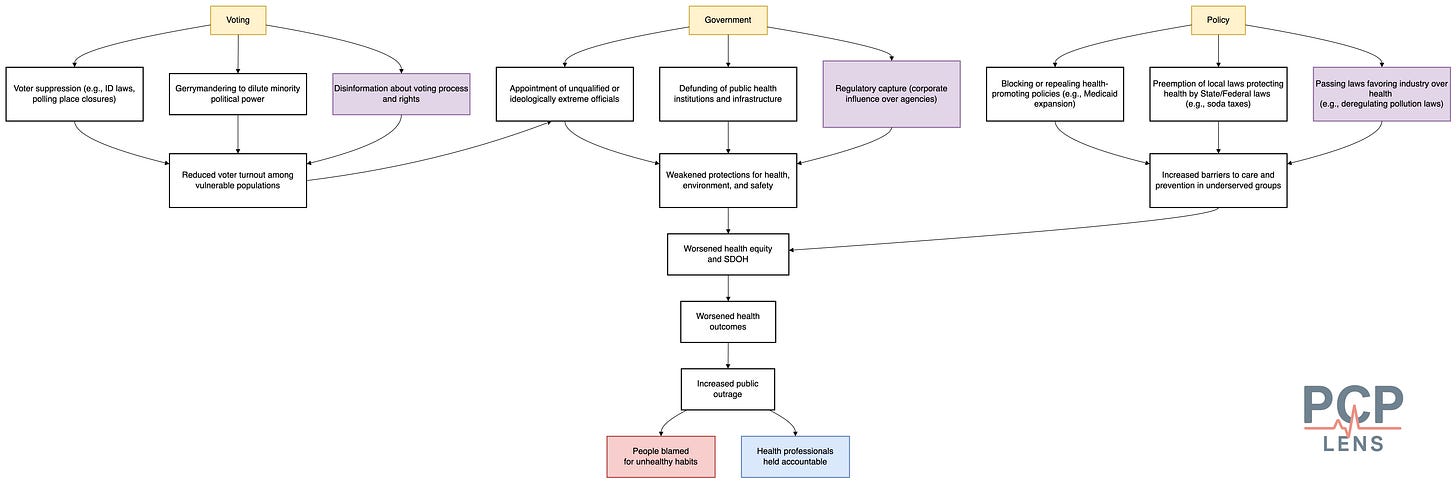

However, this interconnectedness also creates vulnerabilities within the system. The flowchart below illustrates how commercial (purple shaded nodes) and political actors can thwart the system, leading to poor health outcomes. This then leads to shifting blame to individuals, medical professionals, or both.

For example, due to disinformation campaigns, if the public is led to believe that personal choices and immigrants are the leading cause of healthcare expenses, they will elect leaders to ensure that people do not get healthcare. This may lead to dismantling critical infrastructure (e.g., Medicaid), impacting far more people than the public anticipates.

Now that we have looked at how voting, government, and policy shape health, the next question is how these levers are, or should be, applied in practice.

Health in All Policies (HiAP)

Health in All Policies (HiAP) is an approach that emphasizes integrating health considerations into decision-making across all policies that may not be directly or indirectly related to healthcare.

The idea that governments profoundly influence the population's health has existed for quite some time. Integrating health into non-health sectors has roots in the Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion (1986) and intersectoral action for health. In fact, the Ottawa 1986 Charter (PDF Link) mentions explicitly:

The fundamental conditions and resources for health are:

Peace,

Shelter,

Education,

Food

Income

Stable Eco-System

Sustainable Resources

Social Justice

Equity.

This concept gained prominence with the 2006 Finnish EU Presidency, which emphasized intersectoral health and published the “Health in All Policies: Prospects and Potentials” report in collaboration with the WHO.

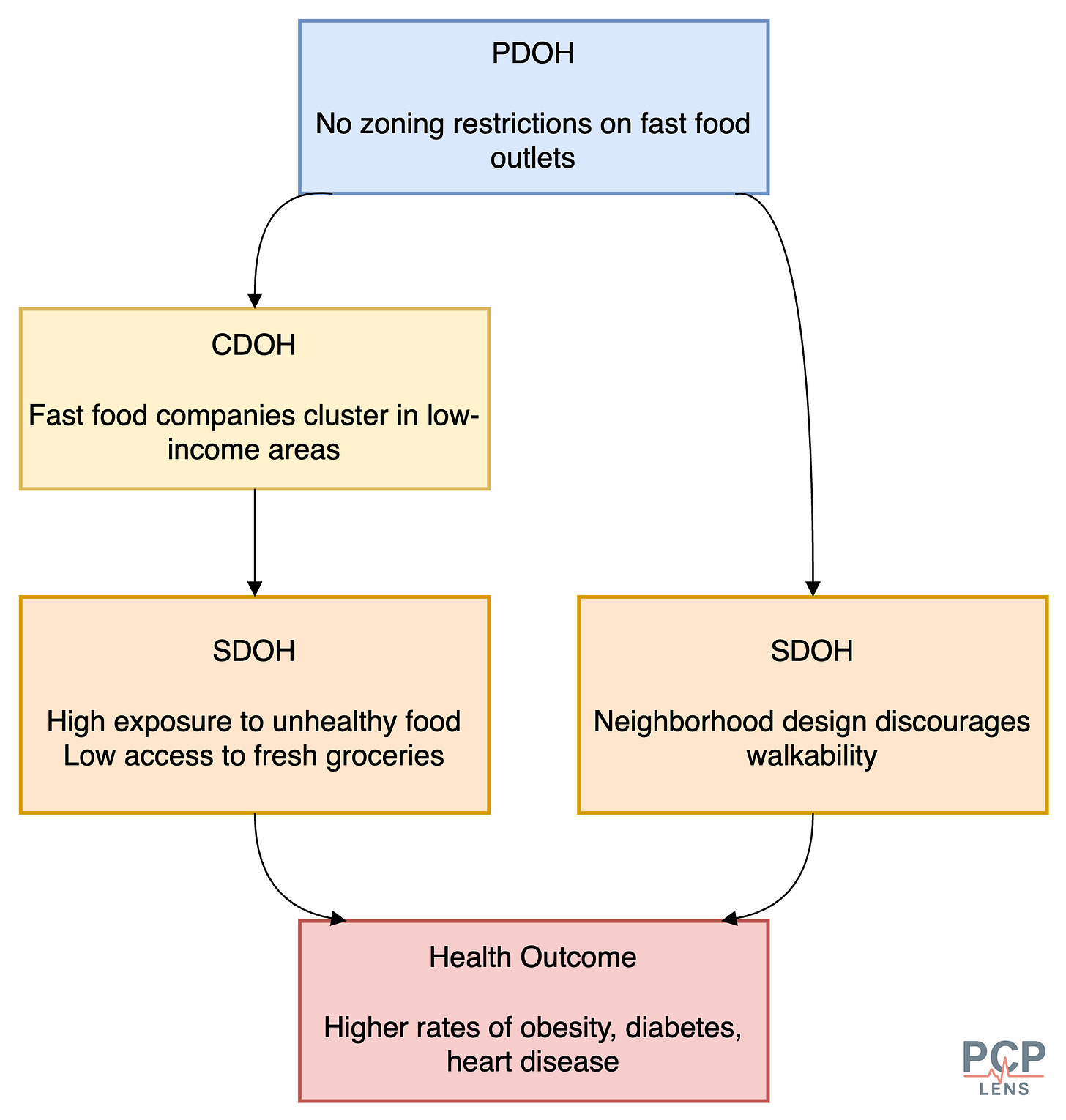

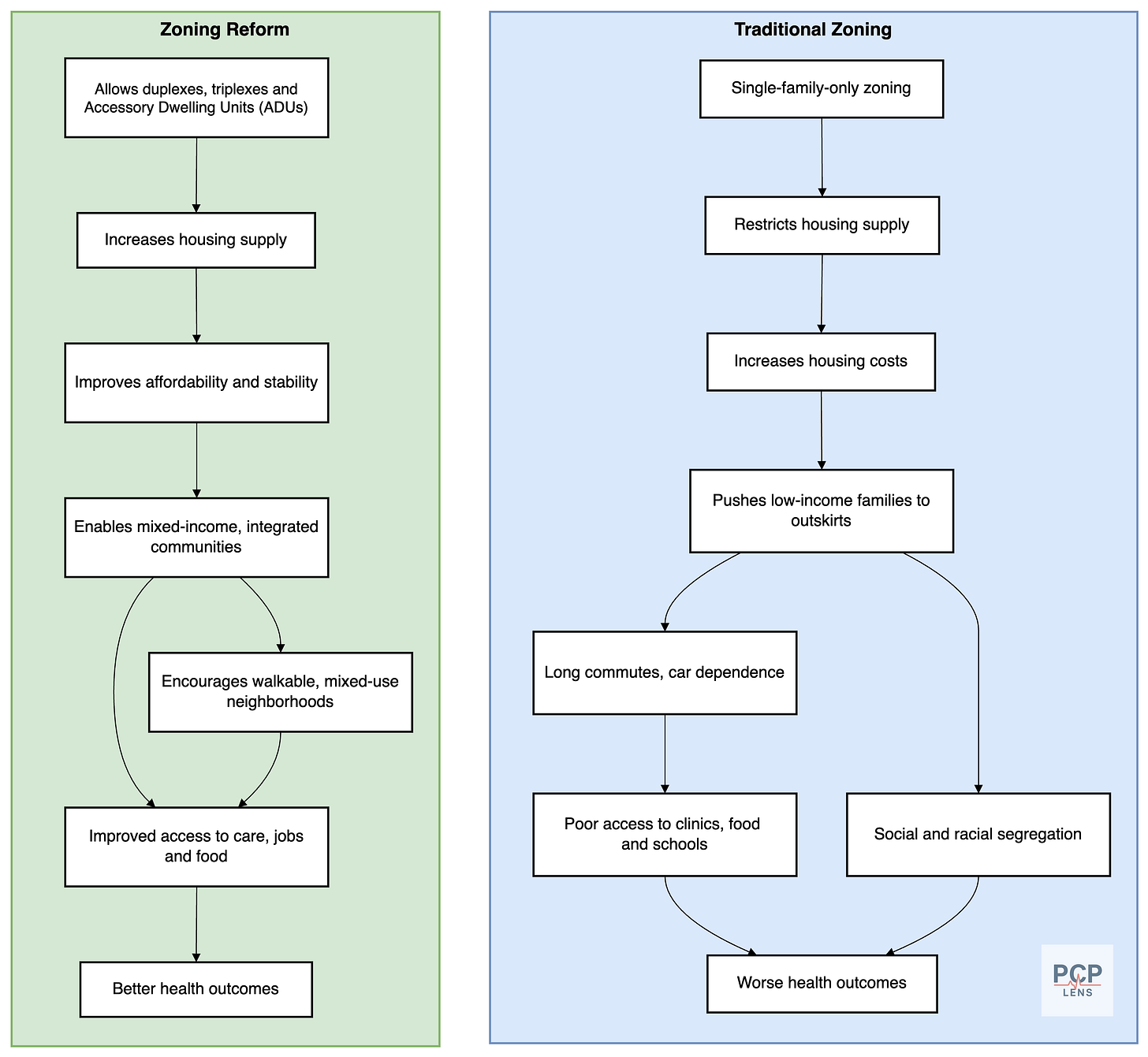

The flowchart below illustrates the effects of using or ignoring the HiAP approach to zoning laws.

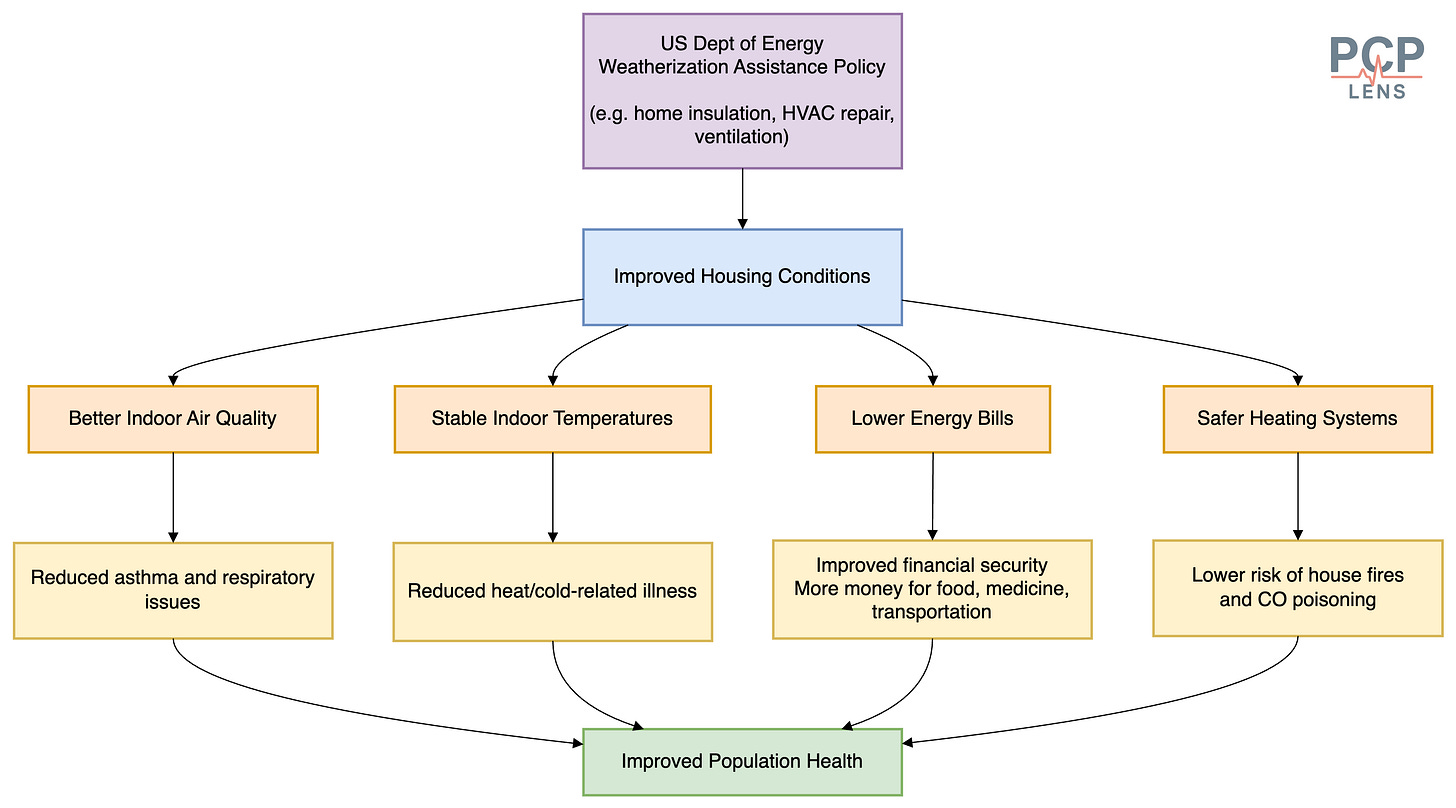

Another example is how the US Department of Energy's weatherization assistance policy improves housing conditions, leading to improved health outcomes.7

Connecting the dots: PDOH, CDOH, and SDOH

The relationship between PDOH and SDOH is causal and hierarchical. CDOH takes advantage of the conditions created by PDOH and SDOH to act as commercial parasites, extracting profits from a vulnerable society. The flowchart below illustrates one pathway by which zoning laws can lead to fast food companies proliferating in low-income areas, worsening health outcomes.

Conclusion

As doctors, sometimes we are told that we should not play politics, keep our heads down, and just take care of patients. However, as I've shown you, the political environment significantly shapes the health of the population. This is why it is becoming imperative for us to understand the role of all the different actors shaping the health of the population.

As the saying goes:

If you're not at the table, you're on the menu.

And we have been on the menu for a long time—first with quality measures, and now under value-based care. The government and commercial actors have successfully changed the narrative that wellness and prevention are the responsibilities of doctors and continue to hold us accountable for circumstances outside our control.

This is why I write PCP Lens. Now it is your turn to share the message.

Up Next

Now that we have covered the Commercial and Political Determinants of Health, we will look at something more structural: the structural determinants of health.

Bai, G., Yehia, F., Chen, W., & Anderson, G. F. (2020). Varying Trends In The Financial Viability Of US Rural Hospitals, 2011–17: Study examines the financial viability of 1,004 US rural hospitals that had consistent rural status in 2011–17. Health Affairs, 39(6), 942–948. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2019.01545

Dawes, D. E., & Williams, D. R. (2020). The Political Determinants of Health (1st edition). Johns Hopkins University Press.

Hajnal, Z., Lajevardi, N., & Nielson, L. (2017). Voter Identification Laws and the Suppression of Minority Votes. The Journal of Politics, 79(2), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.1086/688343

Grimmer, J., & Hersh, E. (2024). How Election Rules Affect Who Wins. Journal of Legal Analysis, 16(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1093/jla/laae001

I am including the 2nd source for readers to balance my claim that Voter ID laws reduce turnout.

Currie, J., DellaVigna, S., Moretti, E., & Pathania, V. (2010). The Effect of Fast Food Restaurants on Obesity and Weight Gain. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2(3), 32–63. https://doi.org/10.1257/pol.2.3.32

Sommers, B. D., Goldman, A. L., Blendon, R. J., Orav, E. J., & Epstein, A. M. (2019). Medicaid Work Requirements—Results from the First Year in Arkansas. The New England Journal of Medicine, 381(11), 1073–1082. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1901772

Wildeman, C., & Wang, E. A. (2017). Mass incarceration, public health, and widening inequality in the USA. The Lancet, 389(10077), 1464–1474. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30259-3

Proponents argue three-strikes laws deter crime by threatening longer sentences, but evidence for a meaningful deterrent effect remains limited and mixed.

Weatherization assistance program | County Health Rankings & Roadmaps. (2022, December 15). https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/strategies-and-solutions/what-works-for-health/strategies/weatherization-assistance-program