Everyone is Pre-Sick

From Framingham to Fitness Trackers

In 1961, the Framingham Heart Study introduced a new phrase into American medicine: “risk factor.”1

For the first time, patients learned that numbers such as blood pressure and cholesterol could predict heart disease years before symptoms appeared. By the late 1970s, millions of Americans were visiting their doctor, not because they were sick, but to “prevent sickness”.

This is the 3rd article in my series “Healers to Healthkeepers.”

Article 1: “From Sewers to Stethoscopes” traced the arc of history from 19th-century sanitation and public works that improved the health of entire towns & cities, to the professionalization of medicine and the rise of the scientific physician.

Article 2: “The Cathedrals of Modern Medicine” reviewed the history of how conditions around WW-II catalyzed a series of changes that led to the emergence of the hospital-insurance duopoly, cementing hospitals as the center of healing.

In this article, I explore how the rise of risk-factor medicine, combined with America’s social fragmentation, made people morally and socially responsible for their own health.

Let’s dive in.

The video version of this article is embedded below and available on my YouTube Channel.

The audio podcast and video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

The Birth of Risk Factor Medicine

By the mid-20th century, the United States had undergone what epidemiologists call the “epidemiologic transition.” Infectious diseases declined dramatically due to improvements in sanitation, living conditions, and vaccines. In this new era, chronic conditions like heart disease, stroke, and diabetes became the dominant cause of morbidity and mortality.

However, these chronic diseases develop silently over decades. In the early 20th century, there was no obvious intervention point until symptoms appeared. This created a conceptual problem: when do you intervene to prevent these heart attacks and strokes?

The answer emerged from a small town outside Boston, called Framingham.

In 1948, researchers launched the Framingham Heart Study,2 which followed thousands of healthy residents to identify what predicted future cardiovascular events. This study, for the first time in medical history, allowed researchers to quantify how traits like blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and smoking habits translated into “disease risk” over time. And the term “risk factor” became a household term.

The concept of “risk factor” transformed medical thinking. Health, now, was no longer a binary state, i.e., sick or well. Health became more of a probability distribution. Everyone occupies a position on a spectrum of future disease risk, which could be measured, tracked, and potentially modified. In other words, everyone was pre-sick, and the goal of the medical profession was to prevent the sickness from taking over.

The Framingham Heart Study forever changed the healthcare landscape, both for better and for worse. While it gave doctors the tools to decrease the “risk of bad outcomes” in individuals, it also led to the medicalization of everyday life, often by expanding the definition of disease for profit.

The Moral Transformation to “Individual Choice”

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it was common for grandparents, unmarried adult children, and sometimes extended relatives to live under one roof.3 This arrangement was due to economic necessity, as survival relied on kinship networks to pool labor, especially to care for the elderly and children.4 Therefore, health and survival were embedded in community reciprocity rather than individual autonomy. This interdependence made decision-making about work, housing, and care collective by default.

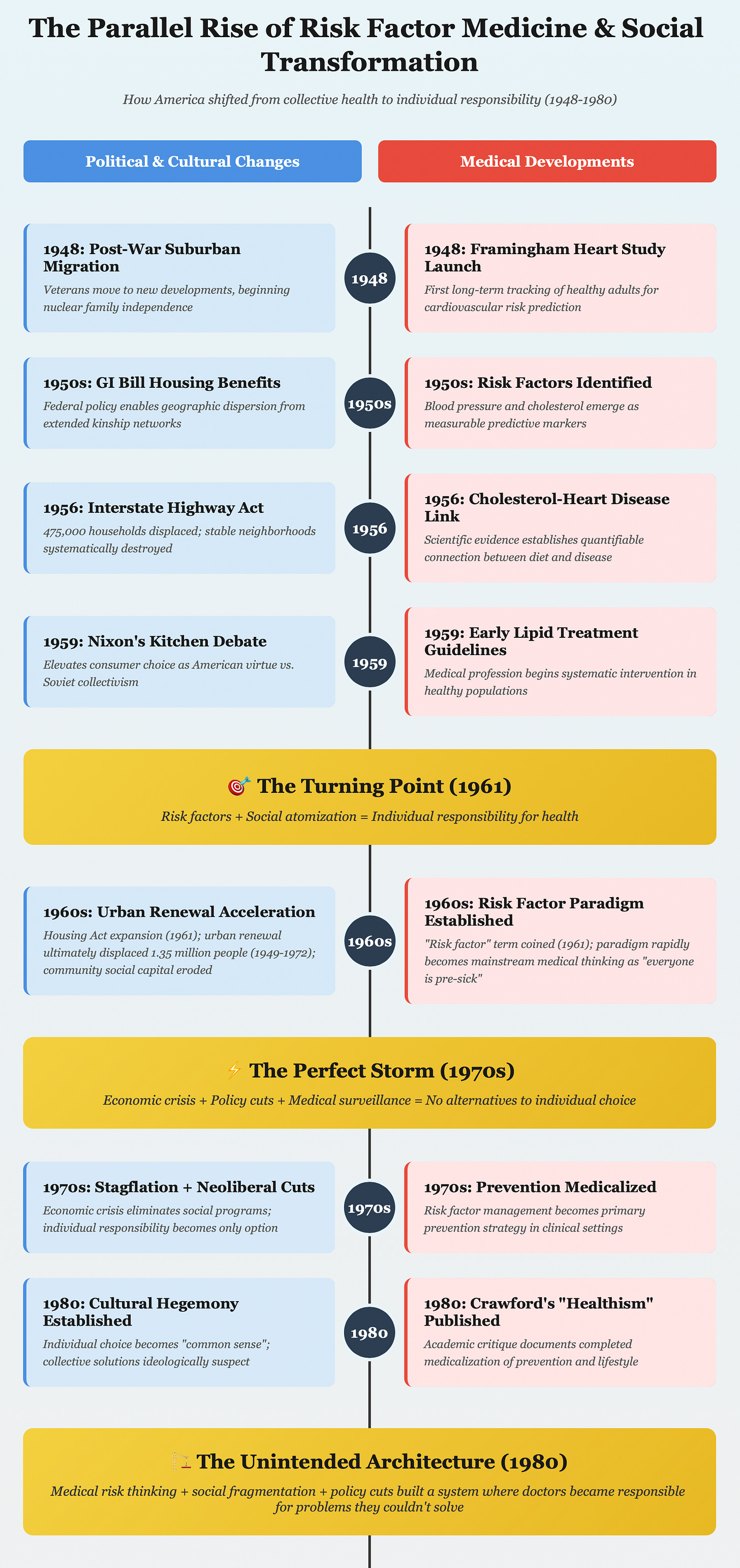

However, several events in the 20th century led to the systematic geographic dispersion of millions of people. A summary of these events is in the table below.

This geographic dispersion had profound sociological consequences. According to Robert Putnam, social capital, “the networks of relationships that enable collective action,”5 requires geographic proximity to function. When families were scattered across the country, communities lost their capacity for pooled labor and mutual support that had sustained previous generations through health crises and economic hardship.

Over time, due to geographic dispersion, traditional institutions based on kinship failed to meet individual needs. Isolated suburban families increasingly turned to professional services and consumer products to solve problems that relatives and neighbors once handled collectively, making individual choice the primary mechanism for meeting previously social needs.

The Cold War provided powerful ideological reinforcement for this emerging consumer individualism. American policymakers explicitly contrasted individual consumer choice with Soviet central planning, making market-based solutions appear patriotic while collective approaches felt un-American.

Fueled by consumerism, migration, and Cold War politics, America’s deeply rooted founding ideals of personal liberty, self-determination, and individual choice gained renewed cultural dominance.

Antonio Gramsci called this ‘cultural hegemony,’ i.e., individual choice became the dominant viewpoint, so much so that alternatives seemed not just impractical but ideologically suspect. While Soviet central planning ultimately failed, the ideological contrast obscured other democratic collective solutions, making market individualism appear as the only viable alternative to collective action.

Prevention Becomes Virtue

Around the same time that individual choice was becoming cultural hegemony, the concept of risk-factor-based medicine emerged from the Framingham Study—and it fit right in. People could manage their individual risk factors for chronic disease without having to worry about others in their community.

The 1970s stagflation crisis accelerated the adoption of neoliberal policies promoting market solutions over collective action. Policymakers began cutting social programs and dismantling public support systems. For many people, the only path-dependent choice became individual responsibility, creating the perfect conditions for what sociologist Robert Crawford called ‘healthism.’6

Crawford defined healthism as:

“The preoccupation with personal health as a primary — often the primary — focus for the definition and achievement of well-being; a goal which is to be attained primarily through the modification of lifestyles.”

Healthism fits right into the cultural hegemony of “individual choice” as it:

Shifted responsibility for health from society to the individual by moralizing health, i.e.:

Equating good health with being a responsible person who takes care of themselves.

Implicitly equating chronic disease with evidence of personal failure or negligence.

Obscured structural determinants, like poverty, racism, and labor exploitation by focusing on personal choices.

Medicalized prevention, turning lifestyle into clinical oversight.

Even in 1980, when Crawford published his article, he criticized healthism for three harmful effects:

It depoliticized health, which removed social and economic conditions from the conversation, protecting status quo policies.

It legitimized victim-blaming

against the disadvantaged population, by treating illness as a personal failure.

against people suggesting alternatives by painting them as “central planners” making paternalistic decisions who assume that people “cannot make their own good decisions.”

It diverted resources away from structural solutions and toward individual-level interventions (e.g., screening & treatment for risk factors in individuals), even when those are less effective.

The cultural hegemony of Healthism made “individual health choices” the default policy choice while erecting barriers for any conversation that involved collective action to keep people healthy (e.g., obesity, community water fluoridation).

The visual below shows the parallel rise of social transformation in America with “Risk Factor Medicine.”

The Tradeoffs

Early screening and diagnosis of risk factors have undoubtedly saved countless lives. Getting patients to quit smoking, control blood pressure, and manage diabetes remains one of the great joys of practicing primary care. Healthism’s focus on individual responsibility and quantifiable targets allows motivated individuals to take control of their health. At the same time, pharmaceutical breakthroughs have developed treatments that not only lower mortality risk but also often improve quality of life.

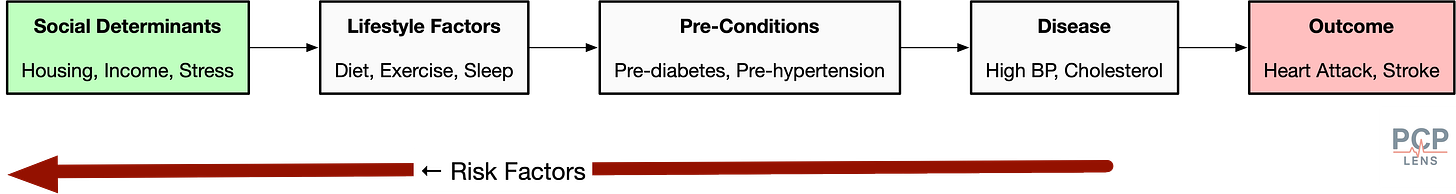

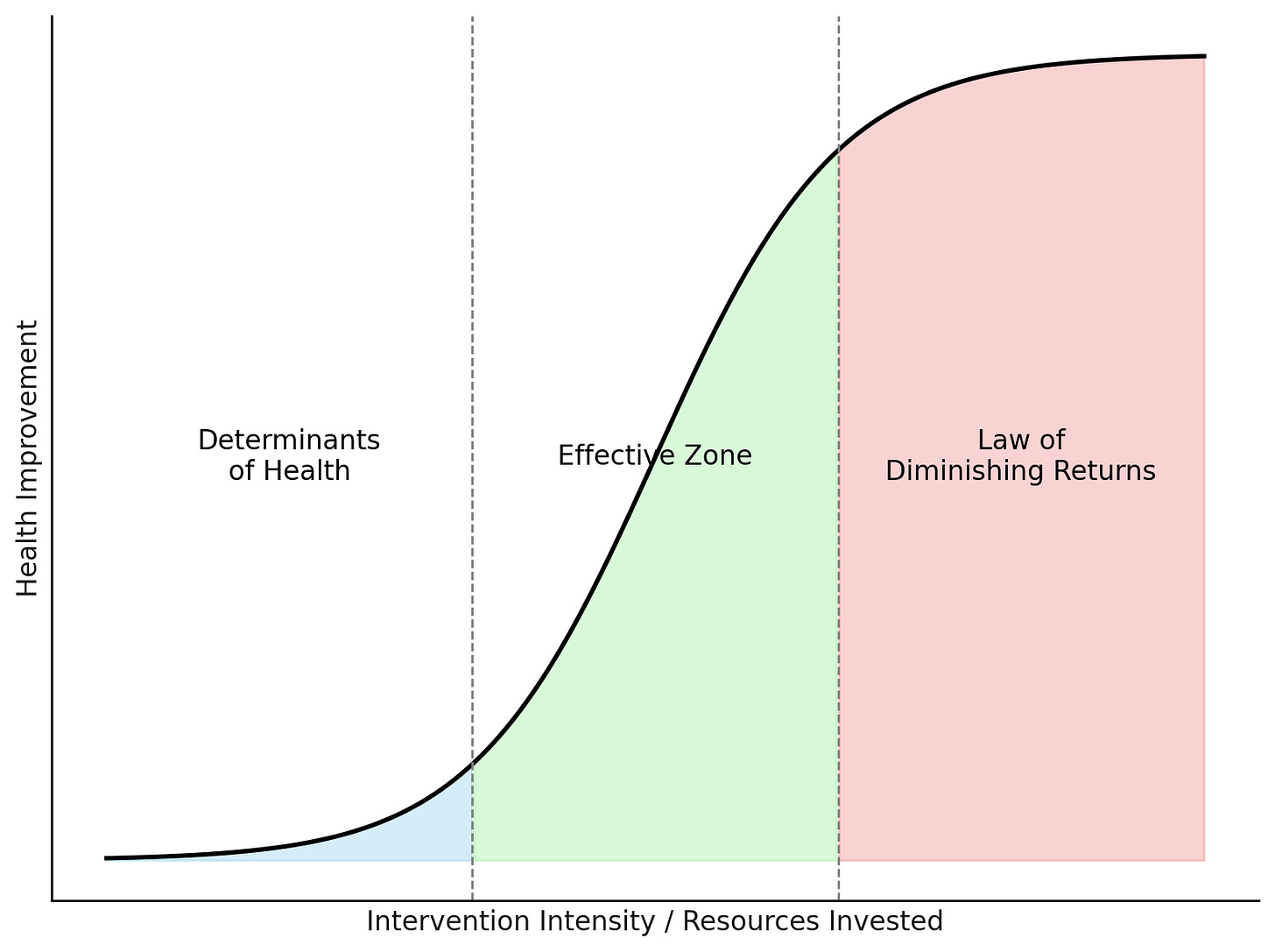

However, these individual success stories obscure significant societal costs. Our relentless focus on risk factors led us to overlook the determinants of health. For example, prescribing BP medications will have minimal effect if the person does not have a place to live, cannot afford them, or lives in a stressful environment. Similarly, prescribing diabetes medications or weight loss methods will not work well if people only have access to fast food. This concept is best illustrated using an S-shaped curve below.

This “Risk Factor Yield Curve” illustrates that the effectiveness of an intervention depends on patients’ underlying social conditions:

The Determinants of Health (DOH) Zone: Patients facing housing instability, food insecurity, or severe poverty, on average, will see fewer benefits from individual medical interventions. We may improve the risk-factor numbers, but social barriers are more likely to predict outcomes.

The Zone of Effectiveness: The ‘sweet spot’ where patients with stable housing, steady income, and basic security can benefit significantly from medical interventions and lifestyle modifications.

The Law of Diminishing Returns Zone: Individuals in this zone face minimal social barriers, and major risk factors are already controlled. Further medical optimization will yield minimal gains in these people.

This Population “Risk-Factor Yield Curve” is an over-simplified representation, but I have also not seen this proposed anywhere in the literature!

Current healthcare spending and quality metrics (aka, Value-Based Care) assume all patients exist in the middle zone. They ignore that many Americans live in conditions where it is very hard for individual medical interventions to overcome structural barriers to health.

Furthermore, risk factor medicine is also highly susceptible to commercial exploitation. The most common ways are:

Change disease definitions, e.g., lower thresholds for risk factors such as cholesterol.

Aggressive marketing to medicalize normality

Sell labs (e.g., know your risk campaigns), drugs, and supplements to lower the “risk of risk factors.”

The virtues and pitfalls of capitalism!

Conclusion

The confluence of 20th-century events with the rise of Risk-Factor Medicine increased our reliance on personal responsibility. As Robert Crawford predicted, this led to the medicalization of normality and the rise of surveillance medicine.

As a society, we appear to be locked in a path dependency where we value individual data points more than the context of a person’s life. This translates into doctors focusing more on lab values than listening to their patients (revealed vs stated patient preferences).

The 21st century is expanding this surveillance medicine to the constant data streams from our fitness trackers, labs that measure the “risk of risk factors,” and private equity-backed companies selling whole body MRI scans. Couple that with consumerism, marketing, free speech, and individual choice, and we are creating a society where everyone is pre-sick.

Up Next

Now that the stage is set for how America came to view health as an individual choice, in the following article, I will explore how insurers and regulators, following the path of least resistance, translated risk-factor medicine into prevention and handed it to doctors.

Kannel, W. B., Dawber, T. R., Kagan, A., Revotskie, N., & Stokes, J. (1961). Factors of risk in the development of coronary heart disease—Six year follow-up experience. The Framingham Study. Annals of Internal Medicine, 55, 33–50. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-55-1-33

Interesting fact: The Framingham Heart Study began in 1948, three years after Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death from a massive cerebral hemorrhage caused by long-standing, poorly controlled hypertension. This was a major political and scientific catalyst that allowed Public health officials at the National Heart Institute (now the NHLBI) to secure funding for the study.

This type of social living still exists in many lower to middle-income countries.

Social Security didn’t exist until 1935, and older people depended on their families.

Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling Alone: America’s Declining Social Capital. Journal of Democracy, 6(1), 65–78. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/1/article/16643

Crawford, R. (1980). Healthism and the medicalization of everyday life. International Journal of Health Services: Planning, Administration, Evaluation, 10(3), 365–388. https://doi.org/10.2190/3H2H-3XJN-3KAY-G9NY