The Curious Case of Water Fluoridation

How a Simple Ion Sparked a Century of Public Health Debate

Since its introduction in 1945, Community Water Fluoridation (CWF) has evolved from a public health triumph to a subject of conspiracy theories. Yet, the underlying story mirrors other determinants of health, notably housing policies, i.e., initial success, incremental controversy, and consequences disproportionately affecting disadvantaged groups.

Let’s dive in.

The video version of this article is embedded below and available on my YouTube Channel.

The audio podcast and video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

Brief History of CWF

The journey of fluoride from an environmental curiosity to a cornerstone of public health began in the early 1900s. A young dentist named Frederick McKay, practicing in Colorado Springs, Colorado, was puzzled by a pervasive brown staining on his patients’ teeth (dental fluorosis), locally known as “Colorado brown stain.” He observed that while aesthetically unappealing, these stained teeth seemed remarkably resistant to decay. This paradoxical observation sparked decades of epidemiological investigation.

In collaboration with dental researcher G.V. Black, McKay confirmed the initial findings in 1916 that the mysterious “mottled enamel” was associated with significantly lower rates of dental caries.1

In the 1930s, Dr. H. Trendley Dean linked tooth staining to fluoride in water. His 1942 “21 Cities Study” showed that optimal fluoride (around 1.0 ppm) reduced cavities with minimal fluorosis, while higher levels increased fluorosis and lower levels offered less decay protection.2

In 1945, Grand Rapids, Michigan, became the first city in the US to adjust the fluoride content of its public water supply. Other communities followed suit, including Newburgh, New York (with Kingston, New York as a control). These initial studies showed:

Relative Risk Reduction (RRR) of 50% to 70% in dental caries among children.

Absolute Risk Reduction (ARR) of 3 to 5 fewer decayed surfaces per child.

These results provided compelling evidence of CWF’s effectiveness.3

The (Misunderstood) Decline of Dental Caries

Myth: CWF does not work as dental caries declined in areas that did not fluoridate water.

In the mid-to-late 1900s, global dental caries rates began to decline in both fluoridated and non-fluoridated areas. This was attributed mainly to the widespread availability and use of other fluoride sources, primarily fluoridated toothpaste, as well as improved oral hygiene and dietary changes.4

CWF still worked, but its efficacy declined in people using fluoridated toothpaste, low sugar intake, and better dental hygiene with access to dental care, i.e., in middle to high-income neighborhoods.

Modern Studies

Due to the overall decline in dental caries, most modern studies on CWF show a lower, but still significant, estimate of CWF on dental caries reduction.

A 2015 Cochrane review5 found CWF to be associated with a:

35% RRR in decayed, missing, or filled primary teeth (DMFT).

26% RRR in decayed, missing, or filled permanent teeth (DMFT).

Another more recent study from England, done in 2023, found:6

17% to 28% of caries in 5-year-olds and a significant

56% reduction of dental extractions.

Several analyses show that for every dollar invested in CWF, approximately $15 to $38 is saved in avoided dental treatment costs.7 However, others have disputed the economic impact of CWF and revised the numbers down to $0 to $3, especially when accounting for the treatment of dental fluorosis (i.e., tooth staining).8

Based on the data above, a few things stand out:

CWF works and reduces dental caries.

Passive delivery method requiring no action on the user’s behalf to benefit.

The impact of CWF is probably unevenly distributed due to the widespread availability of other fluoride-containing products such as toothpastes.

And this differential impact is due to the determinants of health.

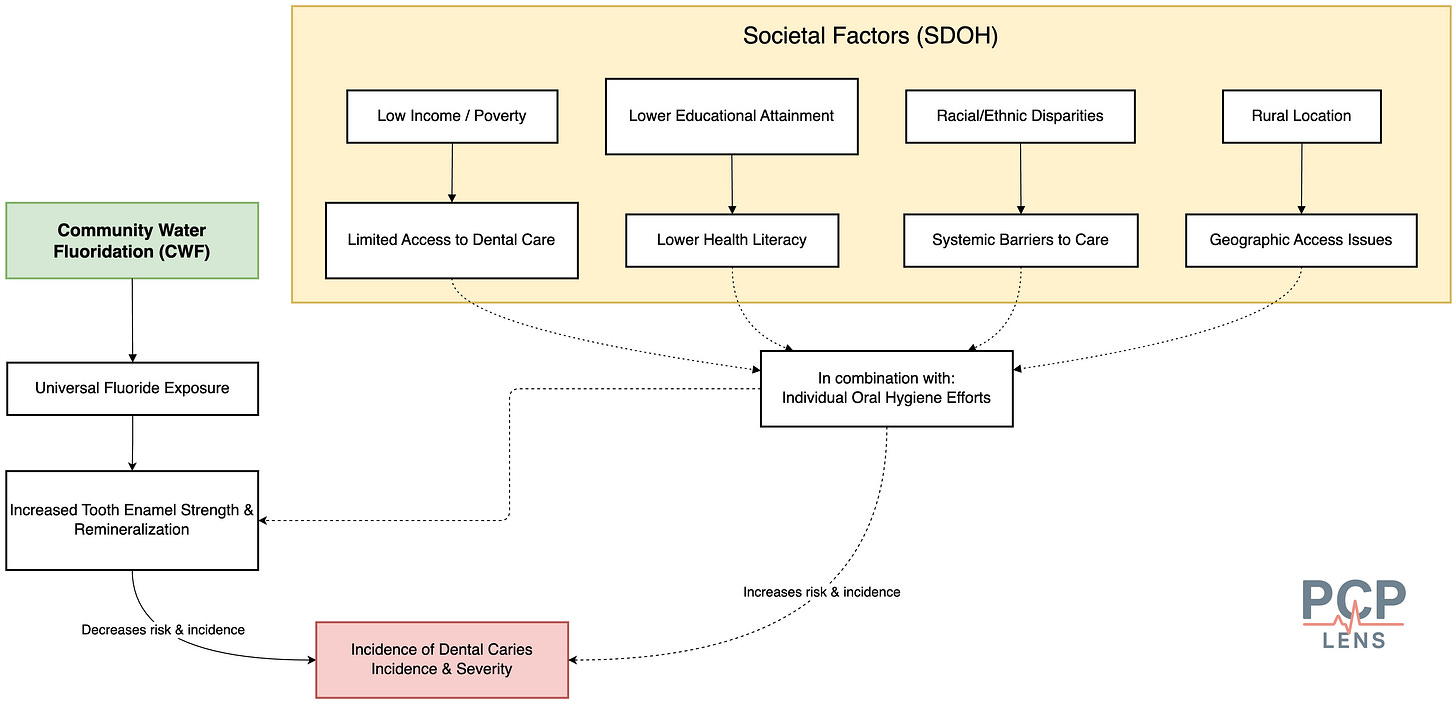

SDOH and CWF

For an overview of how SDOH affects health outcomes, please review my prior article, “The Illusion of Choices.”

The argument, “People should just brush their teeth more,” overlooks the fact that the ability to make healthy choices is itself a privilege shaped by one’s environment. CWF is crucial because it provides protection when these environmental factors fail.

Income & Poverty: Individuals and families with lower incomes often face significant barriers to accessing regular dental care. They may not have dental insurance and may rely more often on emergency dental services.

Education: Low health literacy may lead to poor dental hygiene practices and inability to recognize early warning signs.

Racial/Ethnic disparities and rural location lead to barriers in accessing care.

Removing CWF would disproportionately harm these vulnerable communities. The burden of preventable dental disease, including pain, infections, school absenteeism, and lost workdays, would fall most heavily on those already struggling with limited resources and healthcare access.

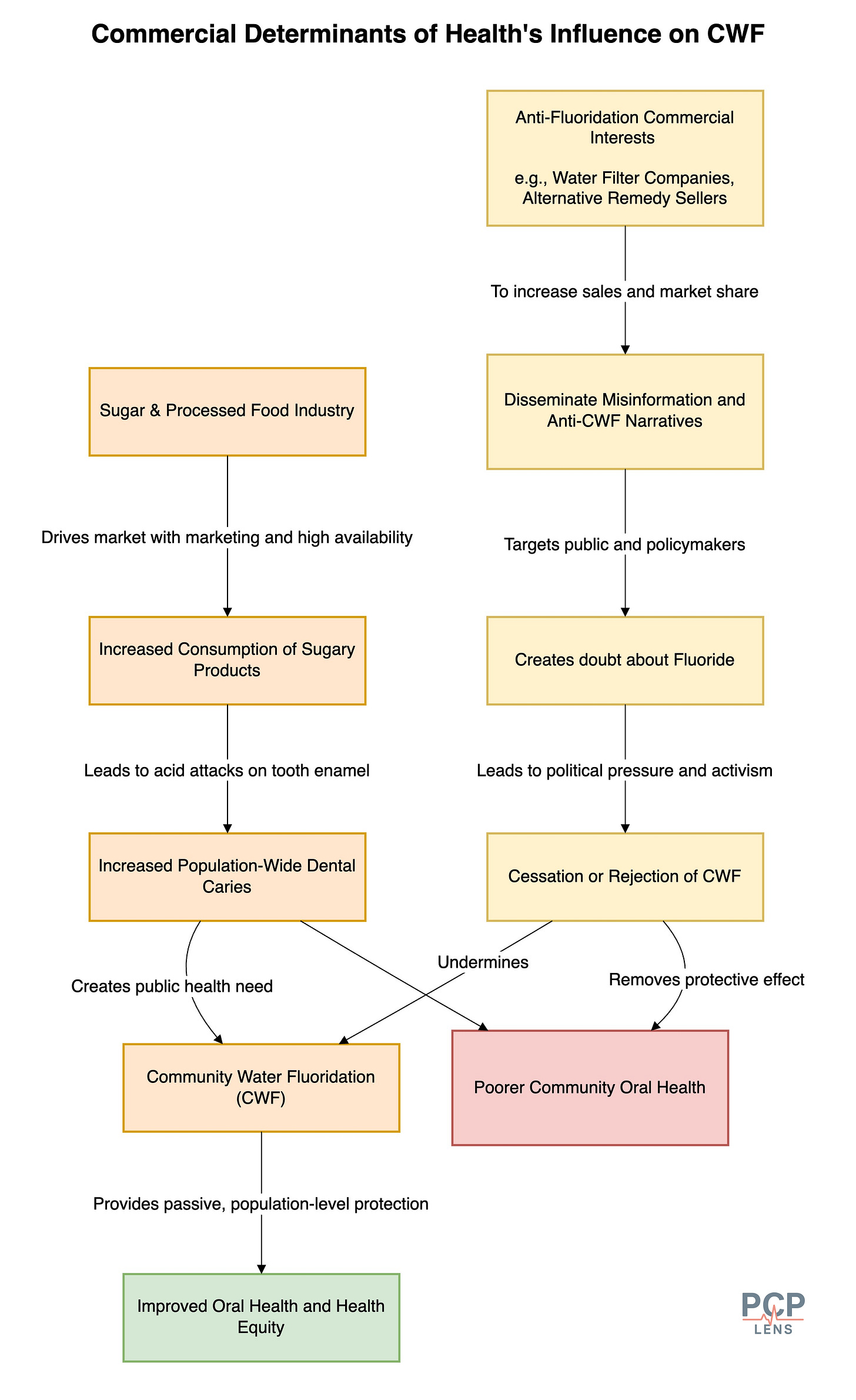

CDOH and CWF

For an overview of how Commercial Determinants of Health (CDOH) affect health outcomes, please review my prior article, “Chronic Conditions, Corporate Causes.”

The Sugar and Processed Food Industries: The pervasive marketing and widespread availability of sugary drinks and processed foods are major drivers of dental caries globally.9 CWF acts as a direct counter-measure, providing a protective effect against the demineralizing impact of dietary sugars. From a public health perspective, CWF offers a population-level defense against the upstream commercial influences that contribute to disease.

Anti-Fluoridation Commercial Interests: Some commercial entities, such as those selling water filters that remove “harmful” fluoride or promoting alternative, often unproven, health remedies, have a vested interest in fostering anti-fluoridation narratives. They actively disseminate misinformation, creating doubt about CWF to sell their products, especially among people with low health literacy.

PDOH and CWF

For an overview of how Structural Determinants of Health (StDOH) affect health outcomes, please review my prior article, “When Policy Fails, Medicine Pays.”

Decisions about CWF are made at the state or local level. It is often driven more by politics and lobbying than by science.

Both supporters (like dental associations and public health agencies) and opponents (including anti-fluoridation groups and sometimes commercial actors) lobby policymakers. Who gets heard often depends less on the strength of evidence than on the prevailing political winds, campaign contributions, and the vocal segment of the population that will be instrumental in winning elections.

In today’s environment of rapid misinformation, actors opposing CWF frame the messaging as “mass medication”10 or “toxic waste,”11 or overemphasize harms without understanding the benefits (more on this later). This erodes trust in public agencies and established science, and can override decades of public health gains.

Calgary’s decision to remove CWF led to an increase in tooth decay, forcing the restoration of CWF. 12

StDOH and CWF

For an overview of how Structural Determinants of Health (StDOH) affect health outcomes, please review my prior article, “The Architecture of Illness.”

The decision to implement and maintain CWF reflects a societal commitment to investing in population-level preventive health. Removing CWF, as mentioned before, is more likely to impact marginalized communities. These communities may lack access to dental care and/or be misled by deceptive advertising, which can lead to the use of fluoride-removing water filters or non-fluoridated toothpaste.

One argument I have heard is that other countries don’t use CWF and still have a lower rate of dental caries. However, these countries are different from the US because of:

Comprehensive dental programs to detect and treat dental caries early

Focus on limiting the use of sugary foods that cause dental caries

And/or use alternative methods for fluoridation:

Salt fluoridation: Germany, Switzerland, Austria, France, Mexico, and Colombia.

Milk Fluoridation: Eastern Europe, Asia, and South America, and is generally provided through school-based programs.

Fluoride Toothpaste Distribution: free or subsidized fluoride toothpaste, especially effective in low-income or disadvantaged areas.

Fluoride Mouth-Rinse Programs (School-based): Japan, Sweden, Norway, and selected regions of Switzerland.

Fluoride Varnish Programs: Targeted programs for vulnerable populations in the UK, Canada, and some Scandinavian countries.

In other words, countries that have removed CWF have established alternative structural programs, typically in the form of comprehensive dental care, with or without alternative methods of fluoridation, to reduce the risk of dental caries.

Fluoride, Fluorosis, and IQ

There is growing concern about the incidence of dental fluorosis, i.e., tooth staining, resulting from exposure to multiple sources of fluoride (such as CWF, toothpaste, etc.). US NHANES surveys show that roughly two-thirds of adolescents now exhibit some degree of fluorosis, although moderate or severe forms remain uncommon (<5%).13 As mentioned earlier, some studies estimate that the cost of treatment for dental fluorosis offsets most cost savings from CWF.

Several recent publications have raised concerns about whether CWF affects IQ in children born to mothers residing in areas with CWF.14 These studies are not definitive but do warrant further investigation and possibly decreasing total fluoride intake in pregnant women and children.

These harms from fluoridation are due to high “total fluoride” intake, and CWF is just one source. And total fluoride intake increases because young children swallow too much toothpaste!

Conclusion

As with any intervention, there are benefits and risks, and they may be unevenly distributed. We have sufficient data to demonstrate that CWF reduces dental caries, which benefits some communities more than others, at the expense of tooth staining and a low likelihood of reduced IQ in children if total fluoride exposure is high during the prenatal period.

We can have a genuine ethical debate about “mass medication,” risk vs. benefits, and the role of individual choice. However, it is also true that dismantling CWF without viable alternatives disproportionately burdens the vulnerable.

Up Next

In the next article, we will look at the role of determinants of health in shaping obesity in the country.

Szpunar, S. M., & Burt, B. A. (1987). Trends in the Prevalence of Dental Fluorosis in the United States: A Review. http://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/handle/2027.42/66368

Dean, H. T., Francis A. Arnold, Jr., & Elvove, E. (1942). Domestic Water and Dental Caries: V. Additional Studies of the Relation of Fluoride Domestic Waters to Dental Caries Experience in 4,425 White Children, Aged 12 to 14 Years, of 13 Cities in 4 States. Public Health Reports (1896-1970), 57(32), 1155–1179. https://doi.org/10.2307/4584182

Arnold, F. A., Likins, R. C., Russell, A. L., & Scott, D. B. (1962). Fifteenth year of the Grand Rapids fluoridation study. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 65(6), 780–785. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.1962.0333

Ast, D. B., Finn, S. B., & McCaffrey, I. (1950). The Newburgh-Kingston caries Fluorine study; dental findings after three years of water fluoridation. American Journal of Public Health and the Nation’s Health, 40(6), 716–724. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.40.6.716

Ast, D. B., Smith, D. J., Wachs, B., & Cantwell, K. T. (1956). Newburgh-Kingston caries-fluorine study. XIV. Combined clinical and roentgenographic dental findings after ten years of fluoride experience. Journal of the American Dental Association (1939), 52(3), 314–325. https://doi.org/10.14219/jada.archive.1956.0042

Dean, H. T., Arnold, F. A., Jay, P., & Knutson, J. W. (1950). Studies on mass control of dental caries through fluoridation of the public water supply. Public Health Reports (Washington, D.C.: 1896), 65(43), 1403–1408.

Sheiham, A. (1984). Changing trends in dental caries. International Journal of Epidemiology, 13(2), 142–147. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/13.2.142

Iheozor-Ejiofor, Z., Worthington, H. V., Walsh, T., O’Malley, L., Clarkson, J. E., Macey, R., Alam, R., Tugwell, P., Welch, V., & Glenny, A.-M. (2015). Water fluoridation for the prevention of dental caries. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2015(6), CD010856. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010856.pub2

Roberts, D. J., Massey, V., Morris, J., Verlander, N. Q., Saei, A., Young, N., Makhani, S., Wilcox, D., Davies, G., White, S., Leonardi, G., Fletcher, T., & Newton, J. (2023). The effect of community water fluoridation on dental caries in children and young people in England: An ecological study. Journal of Public Health (Oxford, England), 45(2), 462–469. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdac066

Griffin, S. O., Jones, K., & Tomar, S. L. (2001). An economic evaluation of community water fluoridation. Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 61(2), 78–86. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-7325.2001.tb03370.x

O’Connell, J., Rockell, J., Ouellet, J., Tomar, S. L., & Maas, W. (2016). Costs And Savings Associated With Community Water Fluoridation In The United States. Health Affairs (Project Hope), 35(12), 2224–2232. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0881

Ko, L., & Thiessen, K. M. (2015). A critique of recent economic evaluations of community water fluoridation. International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health, 21(2), 91–120. https://doi.org/10.1179/2049396714Y.0000000093

Sheiham, A., & James, W. P. T. (2014). A new understanding of the relationship between sugars, dental caries and fluoride use: Implications for limits on sugars consumption. Public Health Nutrition, 17(10), 2176–2184. https://doi.org/10.1017/S136898001400113X

The “mass medication” viewpoint is seen as a genuine ethical dilemma in many circles

The “toxic waste” messaging is an example of taking a kernel of truth and twisting it to achieve political ends.

Burger, D. (2021, August 10). A tale of two cities finds that community water fluoridation prevents caries. ADA News. https://adanews.ada.org/ada-news/2021/august/community-water-fluoridation-prevents-caries/

Neurath, C., Limeback, H., Osmunson, B., Connett, M., Kanter, V., & Wells, C. R. (2019). Dental Fluorosis Trends in US Oral Health Surveys: 1986 to 2012. JDR Clinical and Translational Research, 4(4), 298–308. https://doi.org/10.1177/2380084419830957

Green, R., Lanphear, B., Hornung, R., Flora, D., Martinez-Mier, E. A., Neufeld, R., Ayotte, P., Muckle, G., & Till, C. (2019). Association Between Maternal Fluoride Exposure During Pregnancy and IQ Scores in Offspring in Canada. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(10), 940–948. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1729

Taylor, K. W., Eftim, S. E., Sibrizzi, C. A., Blain, R. B., Magnuson, K., Hartman, P. A., Rooney, A. A., & Bucher, J. R. (2025). Fluoride Exposure and Children’s IQ Scores: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 179(3), 282–292. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2024.5542

Strong piece. The core issue with fluoridation is equity. Those with resources will always find access to fluoride through dental products and care. It is children, low-income families, and marginalized groups who benefit most from community water fluoridation. Removing it without robust alternatives widens disparities and turns a solvable disease into another marker of inequality.