The Illusion of Healthy Choices

A Primer on Social Determinants of Health

Personal responsibility is a powerful idea, but it becomes an illusion when the environment makes the healthy choice the hardest one to make.

It’s easier to quit smoking when those around you encourage you to quit. It is much harder when everyone around you smokes.

This is an example of the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH), the foundational conditions in which people live that profoundly shape their health outcomes.

When I began writing this Determinants of Health (DOH) series, the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) seemed like the natural starting point. But before exploring SDOH, I chose to focus on upstream influences, which I covered in my last 3 articles:

Chronic Conditions, Corporate Causes - Commercial Determinants of Health (CDOH)

When Policy Fails, Medicine Pays - Political Determinants of Health (PDOH)

The Architecture of Health - Structural Determinants of Health (StDOH)

If you haven't read them, I encourage you to do so first, as I will tie these into how they impact SDOH and the health of the population.

Let’s dive in.

The video version of this article is embedded below and available on my YouTube Channel.

The audio podcast and video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

Definition

WHO defines SDOH as:

“The conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age. These circumstances are shaped by the distribution of money, power and resources at global, national and local levels.”

The US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Healthy 2030 goal builds on the WHO definition and divides SDOH into 5 broad categories (all links below are to PDF infographics on the HHS website):

Economic stability: Includes employment, food insecurity, housing instability, and poverty.

Education access and quality: Includes early childhood development and education, enrollment in higher education, high school graduation, and language and literacy.

Healthcare access and quality: Includes access to health services, access to primary care, and health literacy.

Neighborhood and built environment: Includes access to foods that support healthy dietary patterns, crime and violence, environmental conditions, and quality of housing.

Social and community context: Includes civic participation, incarceration, and social cohesion.

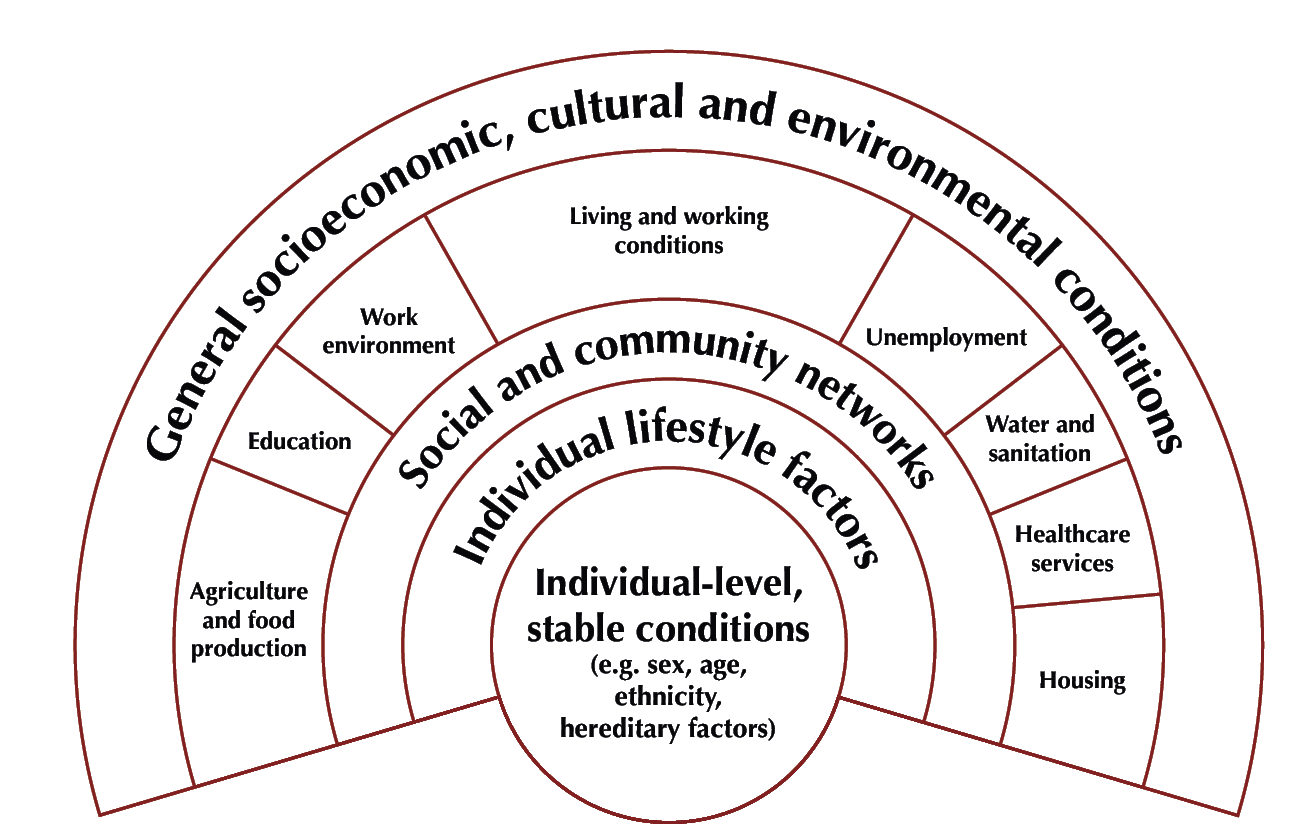

The diagram below shows the interrelated layers of SDOH domains.

SDOH and Health

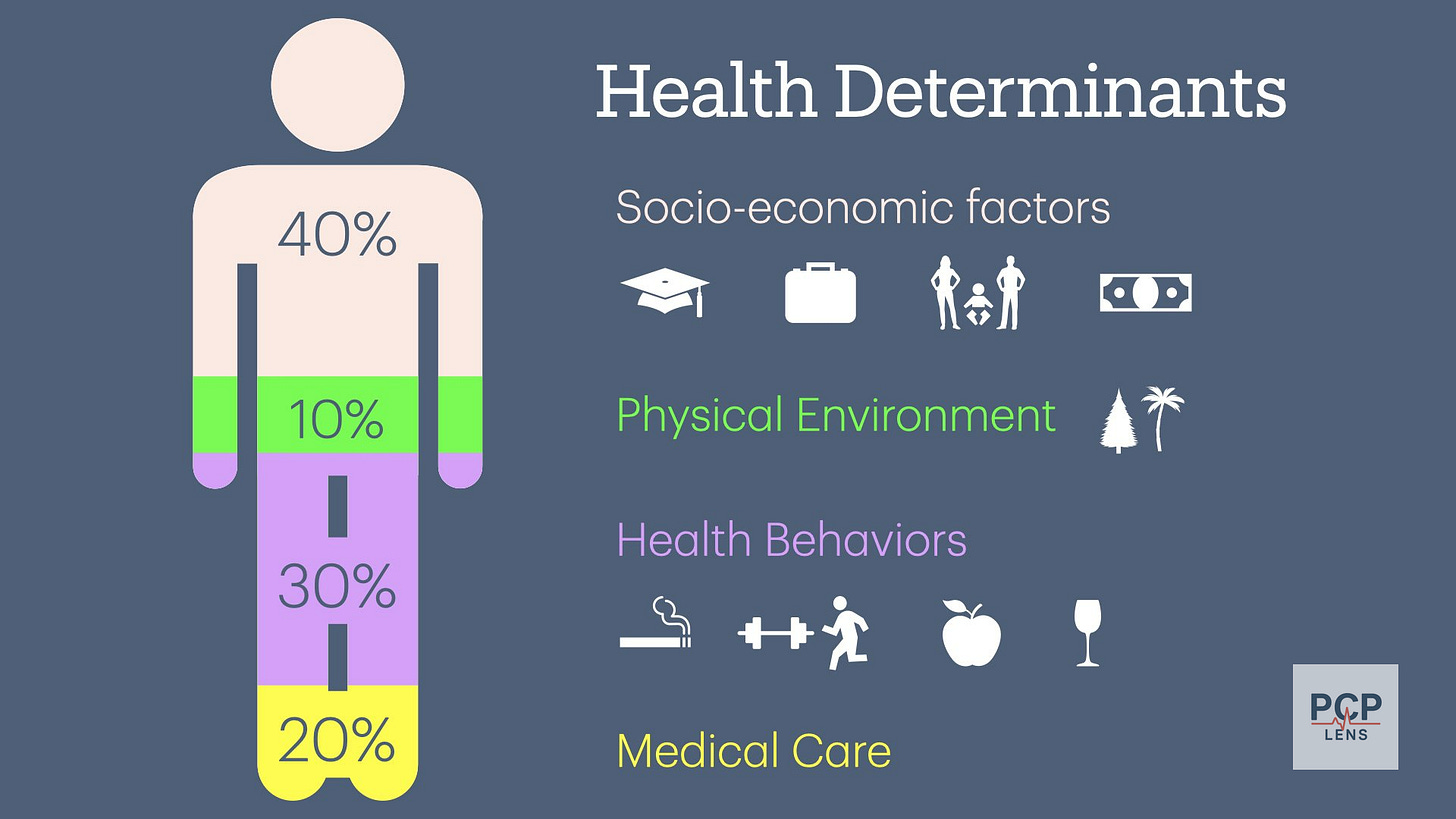

Over the last couple of decades, a substantial amount of evidence suggests that SDOH may account for 30-55% of people's health outcomes, while medical care only accounts for 10-20%.1

In my first article, “From Doctors to Social Workers,” I wrote:

Socioeconomic and environmental factors heavily influence individual risk factors.

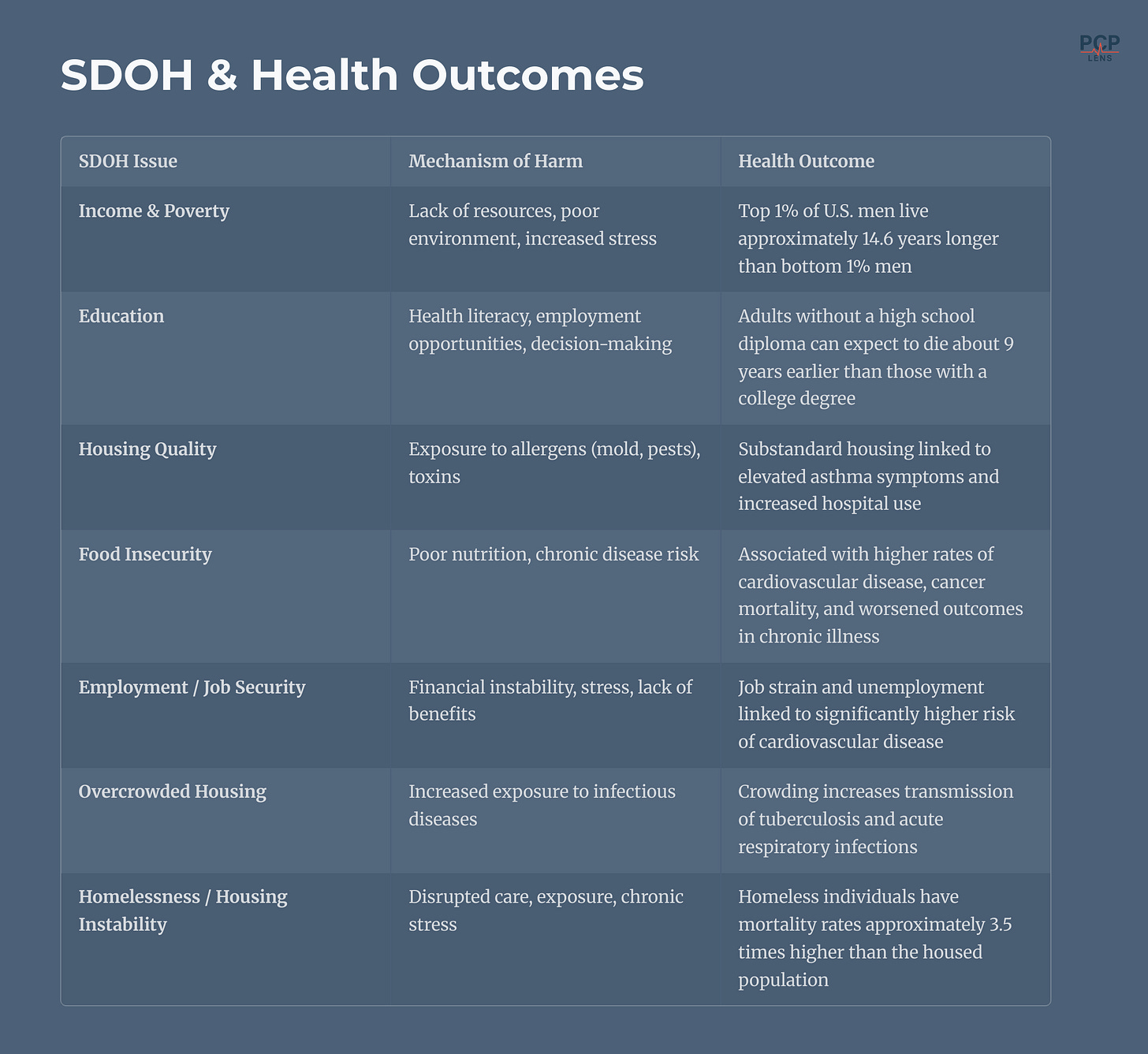

The table below summarizes several SDOH issues, their mechanisms of action, and their impact on health.

I will not go into detail in each of these categories, as the HHS website does an excellent job of summarizing the existing literature and providing references. You can access the information using the following link: “Social Determinants of Health Literature Summaries.”

What I would like to do is continue the housing example from our previous articles to illustrate how housing can lead to poor health outcomes.

Housing as an SDOH

Where you live influences how you live—and, ultimately, how long you live. The conditions of our neighborhood shape nearly every aspect of daily life, including access to safe housing, clean air, healthy food, good schools, decent jobs, and reliable transportation. Our zip codes are better predictors of health outcomes2 than any fancy statistical risk calculator.

Where you live influences how you live—and, ultimately, how long you live.

Housing spans all the determinants of health, including political, structural, commercial, and social determinants.

Political: sets the rules of who gets what housing, and where.

Structural: locks in long-term patterns of segregation and wealth distribution.

Commercial: shapes what is built, where, and for whom, based on profit.

Social: determines daily exposure to health risks (cold, asthma, eviction stress)

In my previous two articles, I examined the political and structural factors affecting housing. This article focuses on how housing, as an SDOH, contributes to poor health outcomes.

Housing as a SDOH refers to the lived conditions of one’s home, i.e., its quality, stability, affordability, as well as the broader neighborhood environment in which that housing exists, i.e., the zip code.

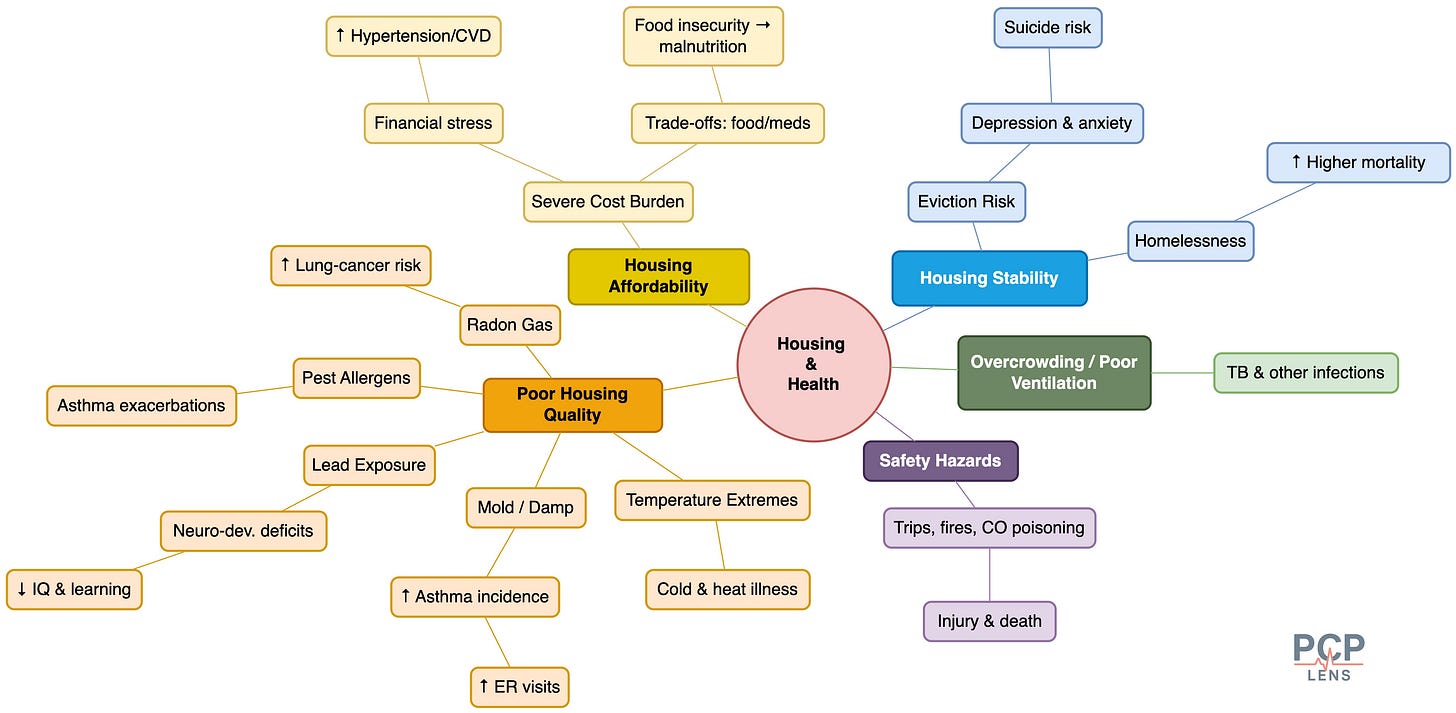

Housing affects health outcomes in numerous ways, as illustrated in the mind map below.

Let's examine three of these pathways in more detail below.

Poor Housing Quality: Mold, Dampness, and Asthma

Poor, old, and crumbling housing infrastructure is prone to water leaks, and poor ventilation creates the conditions for mold and pest infestations.

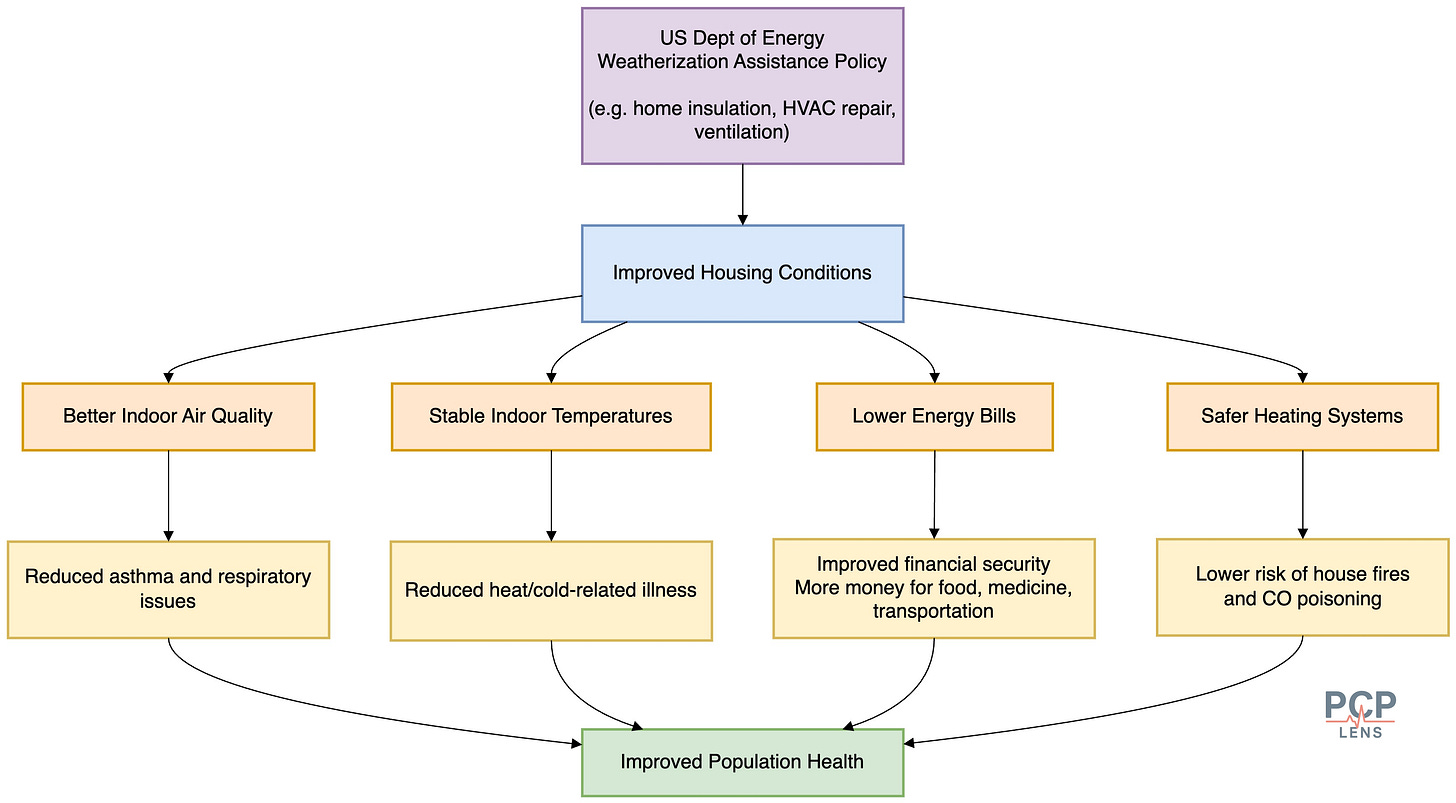

Children living in damp or moldy homes have significantly higher rates of wheezing, asthma symptoms, and emergency department visits.3 Housing remediation, including mold cleanup, ventilation improvements, and pest control, reduces both asthma symptoms and healthcare utilization.

For e.g., the US Department of Energy's weatherization assistance policy improves housing conditions, leading to improved health outcomes. This is an example of the Health in All Policies (HiAP) approach that I discussed in my previous article, “When Policy Fails, Medicine Pays.”

Housing Cost Burden: Rent Trade-Offs and Chronic Disease

When rent exceeds 30% to 50% of a household’s income, families are forced into difficult trade-offs—choosing between paying for housing, food, or medical care. This phenomenon, known as housing cost burden,4 is an economic stressor that leads to poor health outcomes.

Rent-burdened households are more likely to delay or forgo medical care and to face food insecurity.5 Skipped medications, irregular meals, and delayed medical visits make it hard to manage chronic conditions like diabetes and hypertension, leading to higher cardiovascular mortality.

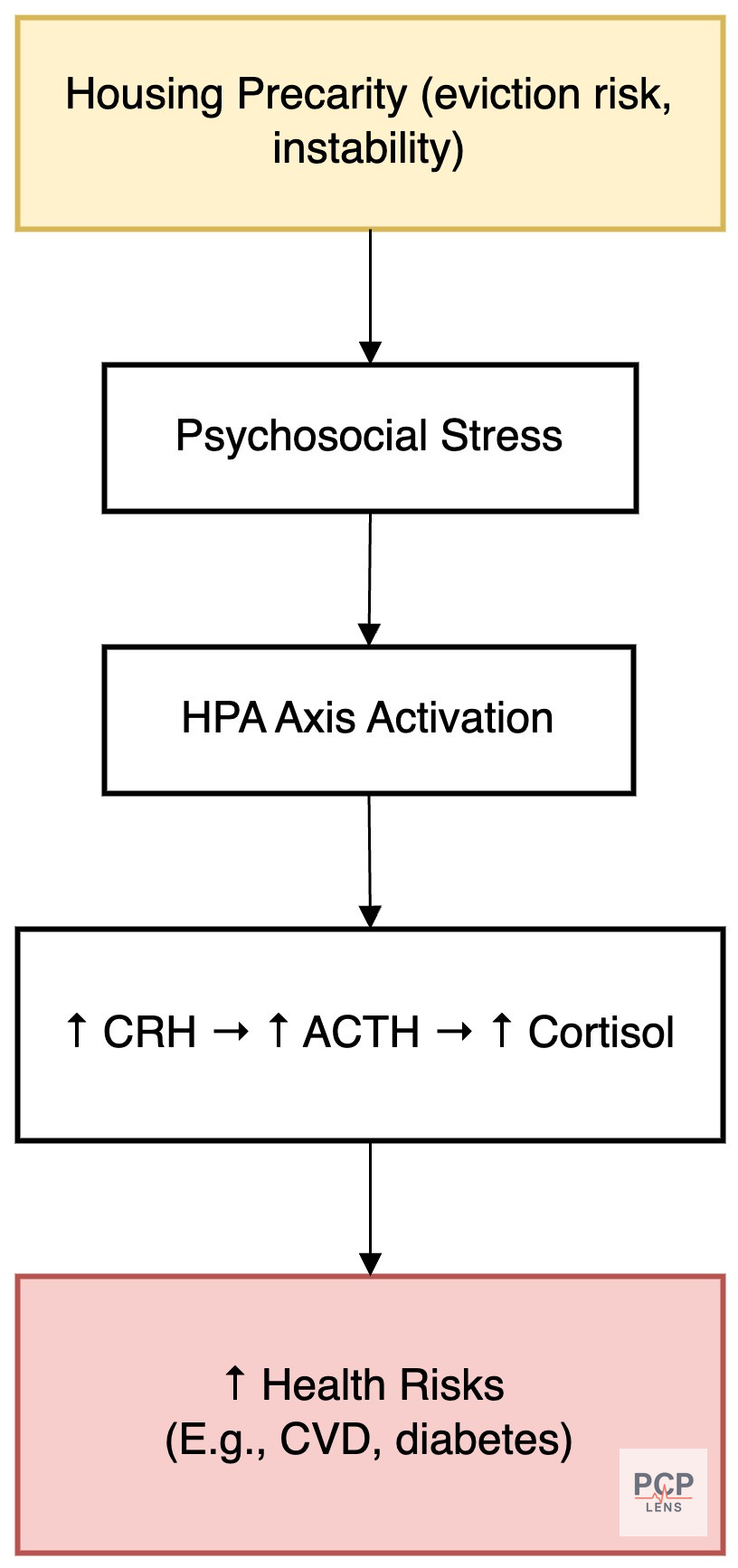

Housing Instability: Eviction and the Biology of Stress

Frequent moves, overcrowding, or the threat of eviction create a baseline of chronic stress that can damage both mental and physical health. Housing instability disrupts schooling, employment, social support networks, and access to consistent medical care.

Studies show eviction increases the risk of suicide and mental health crises.6 Just the looming fear of losing your home is enough to worsen your health. Furthermore, the stress of housing precarity activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, leading to elevated cortisol levels.7 Over time, this contributes to poor sleep, depression, hypertension, and increased cardiovascular risk.

The Illusion of Choice

There is a lot of debate over the role of personal agency versus systemic factors leading to poor health outcomes.

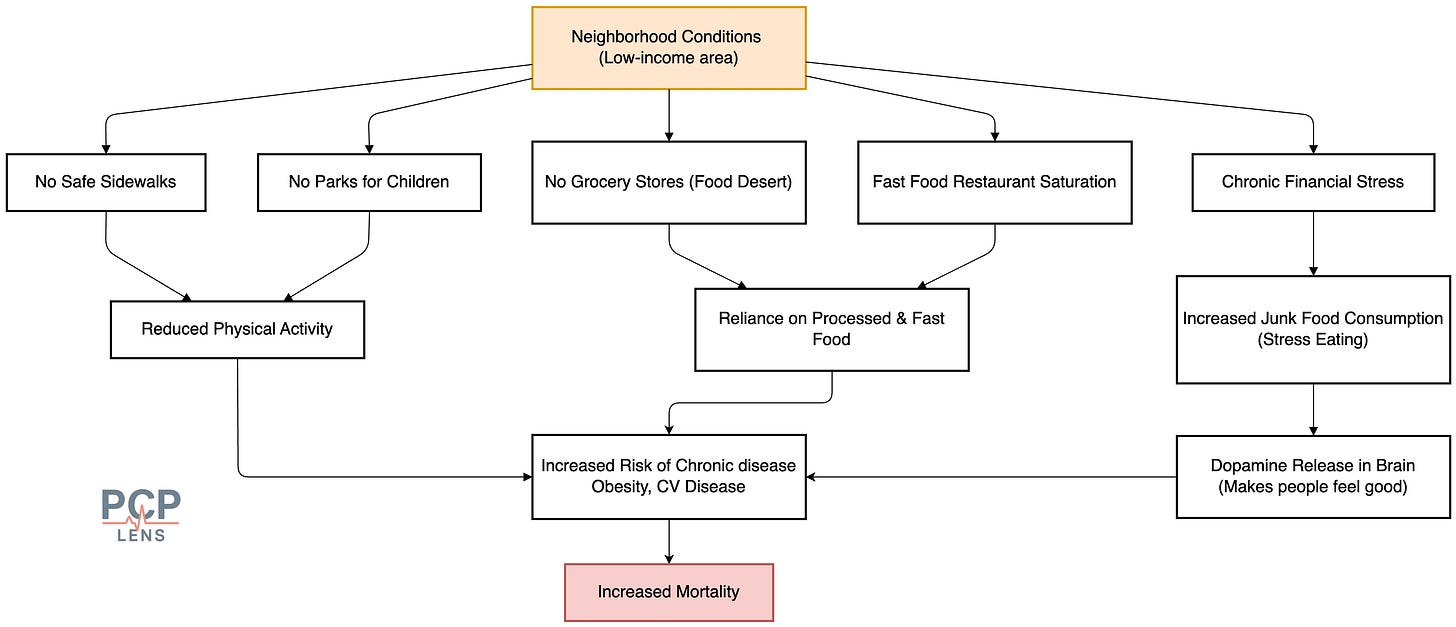

We can criticize people for choosing to eat unhealthy food and not exercise. However, blaming individuals for unhealthy diets or lack of physical activity fails to recognize that housing and neighborhood environments profoundly shape available options.

Living in a low-income neighborhood without safe sidewalks or parks often leads to lower levels of physical activity over a lifetime. Chronic financial stress, combined with limited access to healthy food or time to prepare meals, contributes to an over-reliance on inexpensive, unhealthy food options, often heavily marketed to low-income communities. This creates an environment that fosters unhealthy choices, not because of personal failure, but because the environment constrains available options.

While some individuals may overcome these barriers and make consistently healthy choices, they are the exception, not the norm. To improve health, we need to make the right choice, the easy choice.

Up Next

Now that I've looked at all the major determinants of health, in the next article, I will apply some of these concepts and look at how community water fluoridation impacts our health.

Bhavnani, S. K., Zhang, W., Bao, D., Raji, M., Ajewole, V., Hunter, R., Kuo, Y.-F., Schmidt, S., Pappadis, M. R., Smith, E., Bokov, A., Reistetter, T., Visweswaran, S., & Downer, B. (2023). Subtyping Social Determinants of Health in All of Us: Network Analysis and Visualization Approach. medRxiv, 2023.01.27.23285125. https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.01.27.23285125

Booske, B. C., Athens, J. K., Kindig, D. A., Park, H., & Remington, P. L. (2010). County Health Rankings Working Paper: Different Perspectives For Assigning Weights To Determinants Of Health. https://www.countyhealthrankings.org/sites/default/files/differentPerspectivesForAssigningWeightsToDeterminantsOfHealth.pdf

Warhover, A. (n.d.). Zip Code Overrides DNA Code When It Comes to a Healthy Community. https://doi.org/10.1377/forefront.20140130.036863

Caillaud, D., Leynaert, B., Keirsbulck, M., & Nadif, R. (2018). Indoor mould exposure, asthma and rhinitis: Findings from systematic reviews and recent longitudinal studies. European Respiratory Review, 27(148), 170137. https://doi.org/10.1183/16000617.0137-2017

Bureau, U. C. (n.d.). Nearly Half of Renter Households Are Cost-Burdened, Proportions Differ by Race. Census.Gov. Retrieved June 10, 2025, from https://www.census.gov/newsroom/press-releases/2024/renter-households-cost-burdened-race.html

Denary, W., Fenelon, A., Whittaker, S., Esserman, D., Lipska, K., & Keene, D. E. (2023). Rental Assistance Improves Food Security and Nutrition: An Analysis of National Survey Data. Preventive Medicine, 169, 107453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2023.107453

Fowler, K. A., Gladden, R. M., Vagi, K. J., Barnes, J., & Frazier, L. (2015). Increase in suicides associated with home eviction and foreclosure during the US housing crisis: Findings from 16 National Violent Death Reporting System States, 2005-2010. American Journal of Public Health, 105(2), 311–316. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.301945

Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers, Third Edition. Holt Paperbacks.

Tsigos, C., & Chrousos, G. P. (2002). Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, neuroendocrine factors and stress. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 53(4), 865–871. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(02)00429-4