Obesity: A Symptom of the System

And Why Medicine Alone Can't Solve Obesity

“If obesity is a disease, it’s one manufactured by policy, sold by industry, and blamed on patients and their doctors.”

—My thoughts, rewritten by ChatGPT 4o

A century ago, the typical American family worried about rickets and undernutrition; today, nearly one in two adults live with obesity, and one in four are on track for severe obesity by 2030.1

If clinical medicine alone could solve the problem, the billions already spent on weight-loss drugs,2 bariatric surgery, and BMI quality measures would have turned the tide. Instead, obesity behaves less like a classic disease and more like a symptom of the modern political economy, shaped by the social, political, commercial, and structural determinants of health.

Let’s dive in.

The video version of this article is embedded below and available on my YouTube Channel.

The audio podcast and video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

Definition of Obesity

The WHO and NIH define adult obesity as body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 kg m² and severe/morbid obesity as BMI ≥ 40 kg m².

And yes, the metric is imperfect as it ignores body composition and ethnic variation. But that is a story for another day.

Why do we worry about Obesity?

Obesity is associated with a higher risk of several downstream health-related complications, including:

Cardiometabolic: type 2 diabetes, hypertension, coronary disease, and stroke.

Respiratory: obstructive sleep apnoea and obesity hypoventilation syndrome.

Hepatobiliary: non‑alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)3, now the leading indication for transplant.

Musculoskeletal: osteoarthritis, lower back pain.

Oncology: increased risk of multiple types of cancer.

Reproductive & Psychosocial: infertility, depression, and weight‑based discrimination that itself worsens cardiometabolic health.

With this background, let’s analyze the different determinants of health that lead to obesity.

SDOH & Obesity

For an overview of how SDOH affects health outcomes, please review my prior article, “The Illusion of Choices.”

There is substantial data to confirm that obesity rates are distributed along socioeconomic status lines, especially among women and children:4

Women: 42% obesity rate among those below poverty vs. 29% at higher income levels.

Children: 19% obesity prevalence in low-income families compared to 11% in high-income families.

Men: Less consistent SES relationship. Some higher-income Black, Mexican-American men, and white men with higher-paying, high-stress sedentary jobs have elevated obesity rates.

Besides socio-economic status, environmental, and psychosocial factors, such as neighborhood safety, housing stability, exposure to advertising, and chronic stress, also substantially influence obesity in this population.5

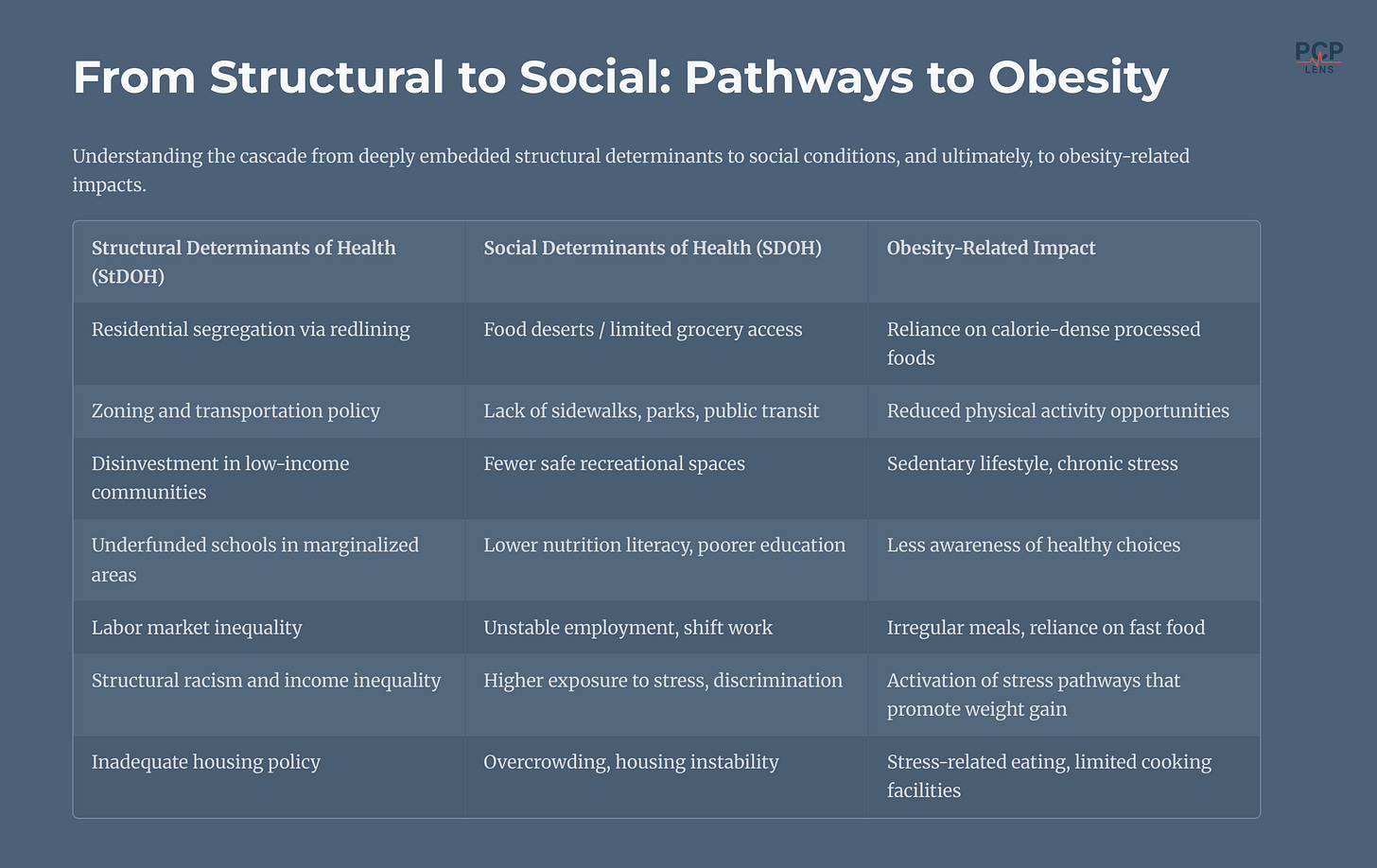

The table below summarizes the various SDOH domains that can increase the risk for obesity.

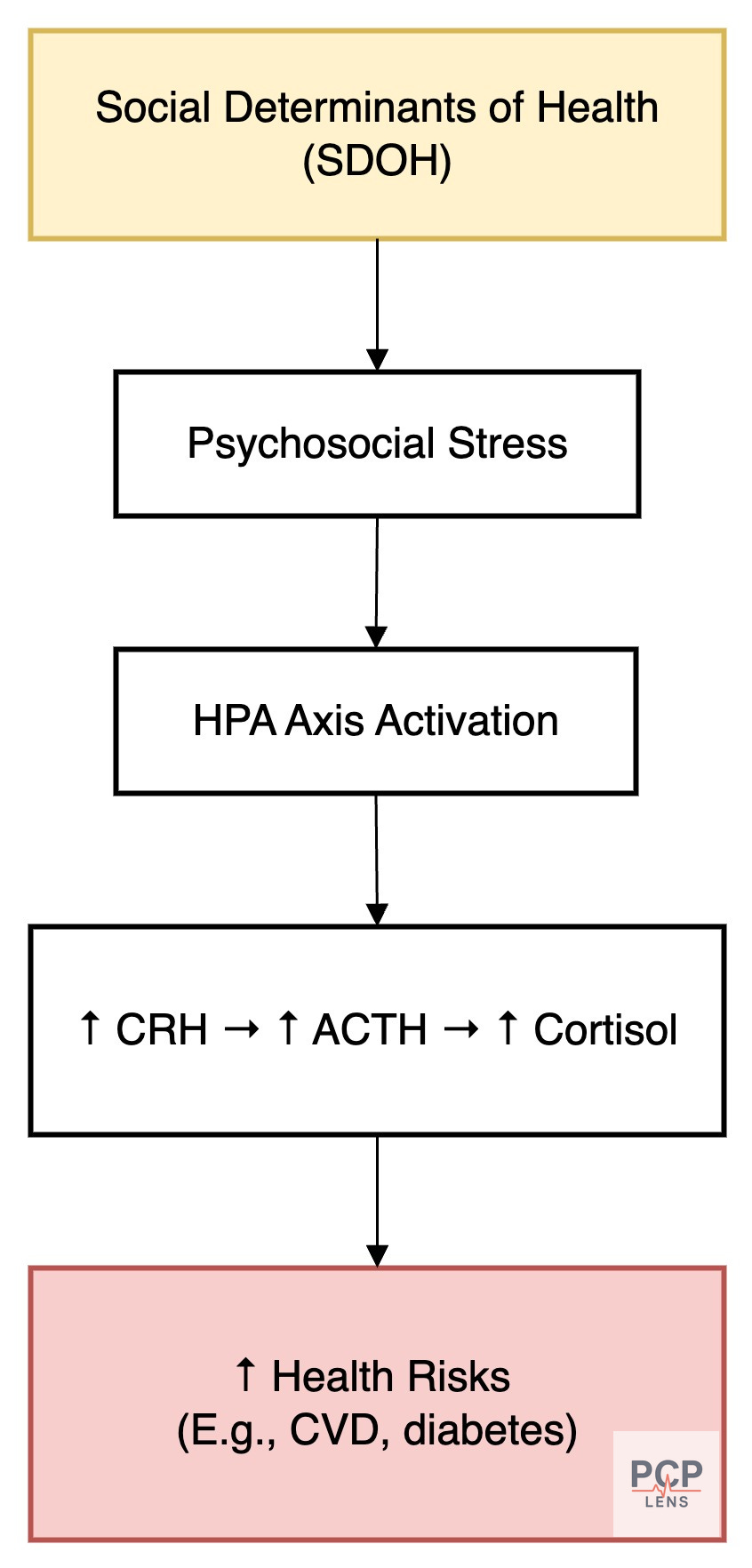

In addition to the risk factors listed above, adverse SDOH conditions deliver a metabolic “one-two punch,” first by shaping unhealthy surroundings, then by activating chronic stress pathways that recalibrate the body’s biology, which further amplifies the risk for obesity.

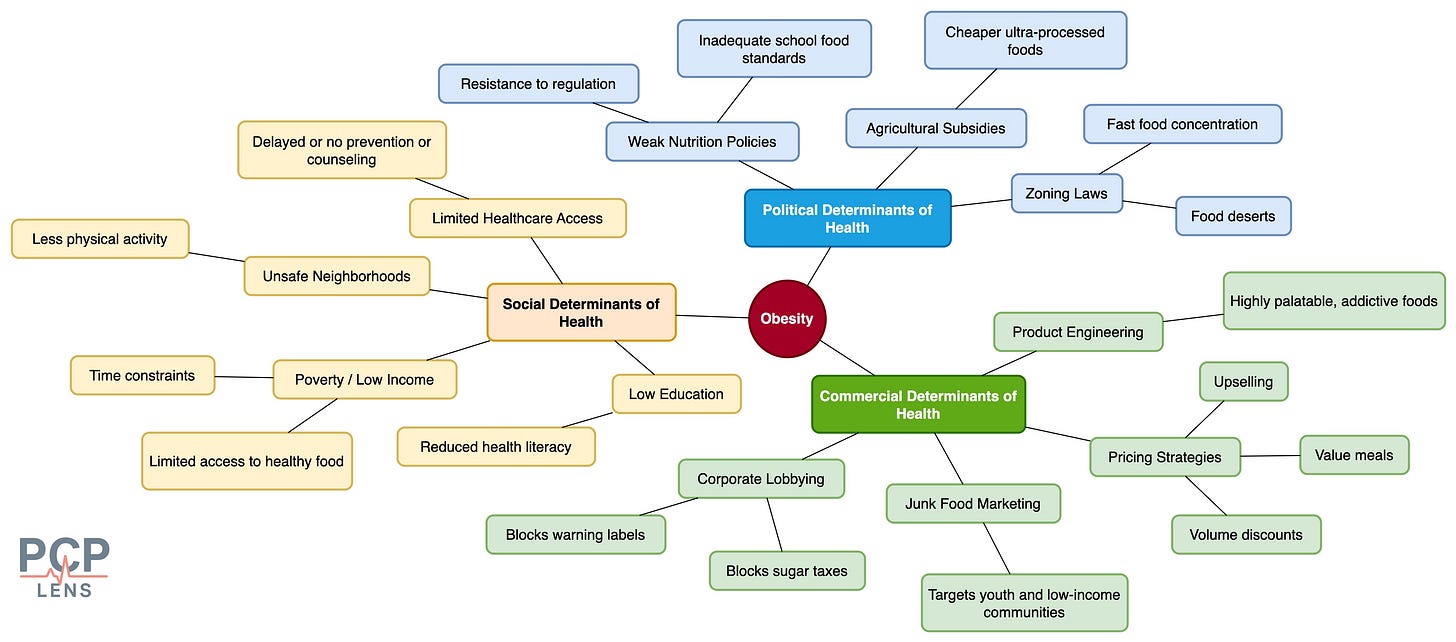

CDOH & Obesity

For an overview of how Commercial Determinants of Health (CDOH) affect health outcomes, please review my prior article, “Chronic Conditions, Corporate Causes.”

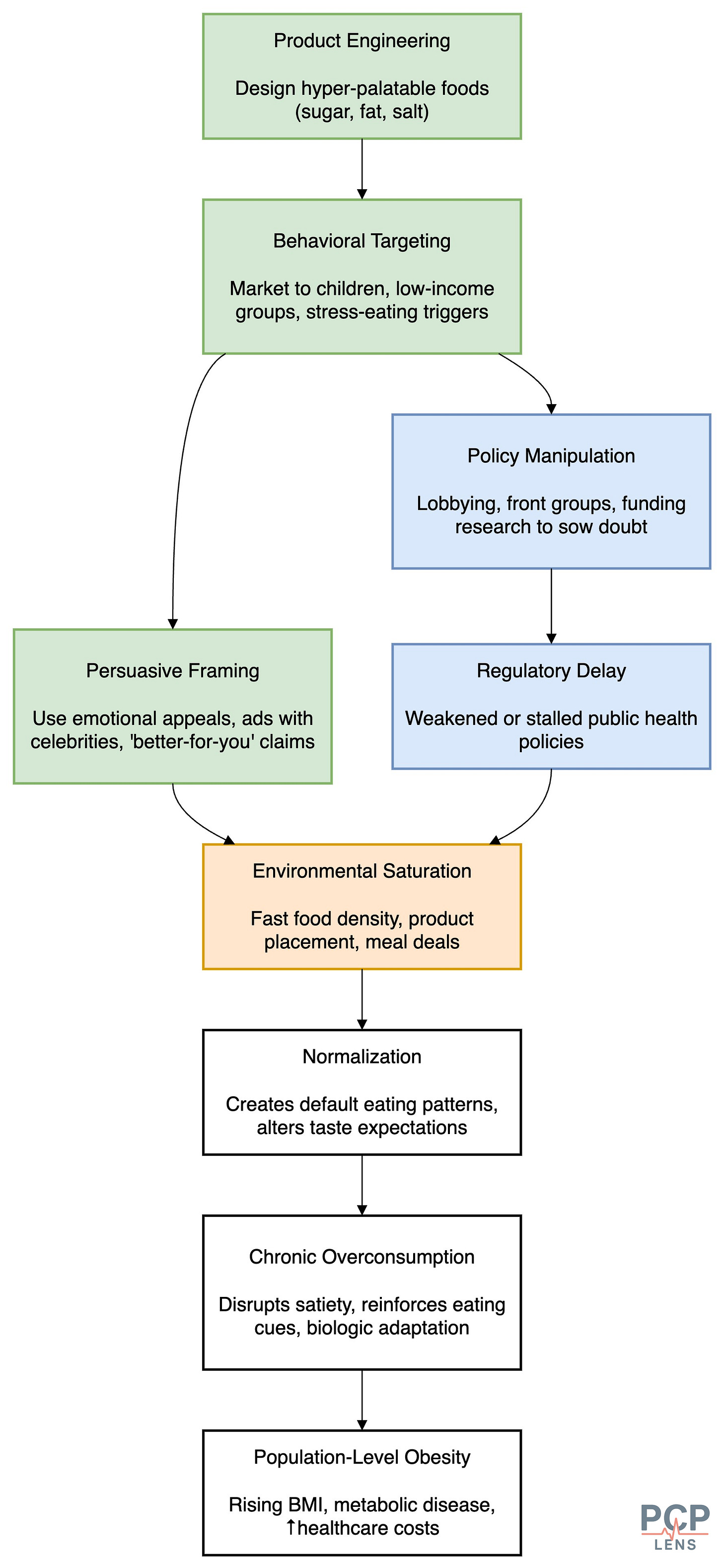

In their pursuit of profit, fast-food industries deliberately design food products to promote overeating. By using high concentrations of sugar, fat, and salt, they create foods that disrupt our natural hunger & satiety mechanisms.6 These “hyper-palatable” foods are engineered to hit a sensory “bliss point,” leading to dopamine-reinforced eating behaviors that mimic neural patterns seen in substance addiction.

For example, in a controlled feeding study, people consumed approximately 500 more calories/day and gained weight when given access to ultra-processed foods, despite reporting similar levels of fullness compared to minimally processed options.7

Next, fast food advertising is a masterclass in behavioral influence, leveraging a sophisticated mix of psychological, economic, and marketing theories to drive consumption, especially among vulnerable populations. These strategies are designed to shape desire, normalize indulgence, and embed fast food into emotional and social rituals. Some of the core frameworks are below:

Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs: Appeals to basic (hunger) and psychological needs (belonging, esteem) by associating fast food with comfort, convenience, and social bonding.

Elaboration Likelihood Model (ELM): Leverages superficial cues, such as attractive visuals, jingles, and celebrity endorsements, rather than rational arguments, making it ideal for low-effort decisions.

AIDA Model (Attention, Interest, Desire, Action): Structures ads to first grab attention (e.g., bold colors), then build interest (food visuals), desire (sizzle sounds, indulgent close-ups), and finally trigger purchase via clear CTAs (call to actions).

Framing Effects: Uses gain-framed (“90% fat-free”) and loss-framed (“don’t miss out”) messages to influence perceptions and urgency without changing actual content.

Emotional and Sensory Branding: Evokes joy, nostalgia, and excitement through sound, imagery, and texture, often overriding nutritional concerns.

Behavioral Economics (Scarcity & Social Proof): Limited-time offers create a sense of urgency (scarcity), while highlighting “fan favorites” and celebrity orders provides social validation (social proof).

Targeting Children and Adolescents: Utilizes cartoons, bright visuals, and rewards to exploit developmental vulnerabilities and establish early brand loyalty (why do you think McDonald's makes its restaurants friendly to kids with small playrooms).

Integrated Marketing Communication (IMC): Ensures consistent brand messaging across TV, apps, social media, and packaging to maintain saturation and coherence.

Data-Driven Personalization: Uses consumer data to tailor ads, promotions, and upsell strategies, maximizing individual-level influence and conversion.

Pricing Strategies: For e.g., corporations use product pricing strategies to promote sugary soda over water. I disucssed this in my previous article, “Chronic Conditions, Corporate Causes.” The flowchart below summarizes this funnel.

And finally, corporate lobbying often blocks or weakens policies such as soda taxes, front-of-pack labeling, and marketing restrictions, i.e., the tools that may help reduce obesity. This political interference prioritizes profit over public health.

Talking about politics, let’s look at the Political Determinants of Health.

PDOH and Obesity

For an overview of how Structural Determinants of Health (StDOH) affect health outcomes, please review my prior article, “When Policy Fails, Medicine Pays.”

Agricultural Subsidy & Supply Chain

Federal subsidies heavily favor commodity crops like corn and soy, which manufacturers use to produce cheap, ultra-processed foods (e.g., high-fructose corn syrup, hydrogenated oils). While economists debate the direct impact of these subsidies on obesity, when coupled with highly efficient supply chains, they distort market pricing, making unhealthy food more affordable and accessible than fresh produce. These cheap foods are then heavily marketed and sold to low-income populations.8

Weak Regulation of Food Marketing and Labeling

Commercial actors using CDOH strategies described above to ensure that they escape regulations, such as sugar taxes, front-of-pack labeling, or restrictions on junk food advertising to children. This regulatory capture ensures that these companies retain and grow their profit margins.

Zoning and Urban Planning Policies

This regulatory capture by commercial entities also applies to zoning laws. These laws often allow clustering of fast food outlets in low-income neighborhoods while restricting supermarkets or green spaces, creating “food deserts” and limiting opportunities for physical activity. People living in such environments are more likely to consume high-calorie foods and have higher rates of obesity.

StDOH and Obesity

For an overview of how Structural Determinants of Health (StDOH) affect health outcomes, please review my prior article, “The Architecture of Illness.”

The Political and Commercial determinants of health create the societal infrastructure and frameworks that lead to the emergence of SDOH.

For example, residential segregation via redlining leads to lower-income people being clustered together. Given that local services, such as schools and parks, are funded via property taxes, these areas are chronically underfunded, leading to lower literacy rates and a lack of spaces for outdoor activities. Since this group of people cannot afford fresh groceries (or don’t have time to cook), fast restaurants proliferate instead of grocery stores.

The table below is a summary of how StDOH affects SDOH, which then, in turn, increases the risk for obesity.

Personal Agency vs Determinants of Health (DOH)

Obesity is often framed as a matter of personal responsibility, i.e., to eat better & move more. And there is some truth to that statement. However, this narrative ignores the role of engineered choice, which is also known as “Manufactured Consent.”

People make decisions, but those decisions are heavily shaped by their environments (StDOH). The reality is that rich and poor people live in different environments. For people with limited income, unhealthy options are often easier, cheaper, and more aggressively marketed to manipulate behavior.

Over time, these external pressures lead to “manufactured consent”; the idea that food & exercise habits reflect true preferences when, in fact, they may reflect limited options. Culture then develops around those constrained choices, and fast food becomes the default meal, and sedentary routines become the norm. This happens, not because of neglect, but because of adaptation. And once a community establishes a culture around these choices, it becomes self-reinforcing, persisting even when the environment improves.

Blaming doctors for obesity prevention is similar to blaming firefighters for the number of house fires in a city, rather than addressing the root causes. This is why obesity prevention, focused on quality metrics and education, has not changed the trajectory of rising obesity rates. As a society, we need to recognize these determinants of health and address their root causes.

Up Next

Now that we have looked at the DOHs (CDOH, PDOH, StDOH, and SDOH) with a couple of examples (fluoride in water and obesity), with the next article, I am embarking on a new series, “Healers to Healthkeepers.”

The goal of this series is to explore how America, over the last century, slowly shifted the narrative of what makes people healthy—from public health infrastructure to doctors!

Ward, Z. J., Bleich, S. N., Cradock, A. L., Barrett, J. L., Giles, C. M., Flax, C., Long, M. W., & Gortmaker, S. L. (2019). Projected U.S. State-Level Prevalence of Adult Obesity and Severe Obesity. New England Journal of Medicine, 381(25), 2440–2450. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1909301

The jury is still out on GLP-1 drugs in reversing societal obesity rates

NAFLD is now called Metabolic Dysfunction-Associated Steatotic Liver Disease (MASLD)

Flegal, K. M., Carroll, M. D., Ogden, C. L., & Curtin, L. R. (2010). Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. JAMA, 303(3), 235–241. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2009.2014

Baez, A. S., Ortiz-Whittingham, L. R., Tarfa, H., Osei Baah, F., Thompson, K., Baumer, Y., & Powell-Wiley, T. M. (2023). Social determinants of health, health disparities, and adiposity. Progress in Cardiovascular Diseases, 78, 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcad.2023.04.011

Fazzino, T. L., Dorling, J. L., Apolzan, J. W., & Martin, C. K. (2021). Meal composition during an ad libitum buffet meal and longitudinal predictions of weight and percent body fat change: The role of hyper-palatable, energy dense, and ultra-processed foods. Appetite, 167, 105592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2021.105592

Hall, K. D., Ayuketah, A., Brychta, R., Cai, H., Cassimatis, T., Chen, K. Y., Chung, S. T., Costa, E., Courville, A., Darcey, V., Fletcher, L. A., Forde, C. G., Gharib, A. M., Guo, J., Howard, R., Joseph, P. V., McGehee, S., Ouwerkerk, R., Raisinger, K., … Zhou, M. (2019). Ultra-Processed Diets Cause Excess Calorie Intake and Weight Gain: An Inpatient Randomized Controlled Trial of Ad Libitum Food Intake. Cell Metabolism, 30(1), 67-77.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmet.2019.05.008

My research on the role of agricultural subsidies showed mixed results on its effect on obesity. I am not sure how much of the research is obscured by industry influence.