The Ritual of Care

How the Annual Physical Became a Billion Dollar Surveillance Machine

The philosophy of the Annual Physical is simple: vigilance, however modest, can defy the randomness of disease.

This is the 4th article in my “Healers to Healthkeepers” series. In the first four, I discussed how we converted collective problems (e.g., public health) into individual responsibilities, and then measured them as quality metrics to demonstrate progress.

From Sewers to Stethoscopes showed how 19th-century engineers laid the foundations of public health.

The Cathedrals of Modern Medicine explained how postwar financing and the Hill-Burton Act cemented hospitals and insurance as the de facto healthcare system.

Everyone Is Pre-Sick followed the rise of risk-factor medicine and how America successfully transitioned from collective to individual responsibility for health.

The Scorekeepers of American Medicine looked at how quality measures became embedded in healthcare due to our focus on individual responsibility and our 3rd party payment system.

This article looks at how the Annual Physical evolved into a ritual of modern medicine, sitting at the crossroads of prevention, measurement, and cultural symbolism.

Let’s dive in.

The video version of this article is embedded below and available on my YouTube Channel.

The audio podcast and video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

Smoke in the Exam Room

From 2002 to 2004, approximately 44 million Americans underwent annual physical examinations, consuming over $8 billion annually, almost equal to the entire national spending on breast cancer care.1

So, before we dig into the history of the Annual Exam, the central question is, “Do Annual Physical exams even help?” In other words, do they increase our likelihood of living longer? And the answer from available evidence is a minimal benefit at best—at the population level.

Two systematic reviews of randomized controlled trials (the second one involving over 250,000 participants) have shown that annual physical examinations in people without symptoms provide no reduction in total mortality, cardiovascular mortality, or cancer mortality.2 And one meta-analysis of observational studies showed a 45% lower hazard for mortality (highly subject to patient selection and amplification bias).3

As with any research study, these studies are population-based studies. One could argue that many individuals will benefit from the Annual Physical, e.g., by early detection and intervention for hypertension and diabetes. But again, these values speak more to our focus on preventing disease in individuals than in the population.

The paradox of the Annual Physical’s persistence despite a lack of scientific evidence only makes sense once we look at the history of the Annual Physical Exam.

(A good article on the history of the Annual Exam was published in the Annals of Internal Medicine, with links to historical archives.4 )

The Spark of an Idea

In 1861, British physician Horace Dobell published “Lectures on the Germs and Vestiges of Disease, and on the Prevention of the Invasion and Fatality of Disease by Periodical Examinations” (PDF Link). In these lectures, he proposed that disease was not a sudden event but a process, and the highest duty of the physician is to find these processes at their earliest stage and remedy them.

As a chest physician, Dobell’s focus likely stemmed from the challenge of detecting & treating tuberculosis early, which was universally fatal without modern antibiotics (context always matters!).

At the dawn of the 20th century, George Gould urged the American Medical Association (AMA) to adopt “periodic biologic examinations” as a new standard of care. The exam, he argued, would allow doctors to study the early course of disease, protect patients from unseen harm, and elevate medicine’s role in society.5

These early ideas formed the spark for the “Annual Physical.” But this spark needed kindling to become a fire.

Laying the Kindling

At the same time, George Gould was proposing “periodic biologic exams,” Life Insurance companies realized that they could use these exams to screen & exclude policyholders, to boost profits.

Once the “physical exam” gained a foothold to exclude “unhealthy people” from life insurance policies, the next logical step was to keep paying customers alive longer. Life insurance companies began employing doctors to conduct detailed, head-to-toe exams on policyholders in an effort to identify diseases early and intervene to reduce mortality.

By 1923, organizations like the Life Extension Institute, led by Eugene Lyman Fisk, had conducted over 250,000 Annual Physicals, boasting that they lowered mortality among policyholders and generated handsome returns for insurers. In fact, most of the early evidence that “Annual Exams” decreased mortality was the “actuarial analysis” done by life insurance companies (which later turned out to be inaccurate).

Meanwhile, the passage of workers’ compensation legislation in the early 1900s created a need to detect and monitor physical conditions that might predispose employees to injure themselves or others on the job.6 These laws popularized pre-employment and routine occupational exams conducted by a “company doctor” in high-risk industries to document the baseline health status of employees in case of a work-related injury.

By the 1920s, the American Medical Association (AMA) had officially endorsed the periodic health examination and launched campaigns to persuade the public to undergo one annually (e.g., “have a health exam on your birthday”). This was done for several reasons:

The new cadre of scientific-physicians, after publication of the Flexner Report in 1910, believed that they could help people.

It provided recurring revenue.

The emerging health insurance industry used the annual exam to justify premiums.

The combination of annual life insurance exams, “workplace exams,” and AMA campaigns promoting the idea that every American should undergo an annual exam laid the kindling in the early 20th century. This kindling would then ignite into a widespread fire by the mid-20th century.

A Fire Erupts

Building upon the model pioneered by Life Insurance companies, in the early to mid-20th Century, large companies created “Executive Physicals” generally in partnership with local hospitals. These “executive physicals” were comprehensive exams and tests for senior managers and were designed to protect the company from economic catastrophe due to sudden illness or the death of a key leader.

This practice was later expanded to all workers in the form of employee wellness programs as an attempt to reduce absenteeism and improve productivity across the workforce.

The expansion of the “annual exam” also coincided with the rise of risk factor medicine and healthism that I discussed in my previous article, “Everyone is Pre-Sick.” This intersection benefited all parties involved:

Healthism supplied the moral framework and put social pressure on people to undergo an Annual Physical.

Doctors gained a new clinical role by tracking & treating risk factors.

Employers saw a tool to cut absenteeism and improve productivity.

By the late 20th century, the annual physical examination had become firmly established in American culture. It was viewed as a workplace benefit and a moral duty, but it would soon be exploited by health plans eager to demonstrate that they were spending money wisely.

The Inferno of Metrics

From my previous article, “The Scorekeepers of American Medicine:”

As public confidence in HMOs waned in the 1990s, market pressure forced health plans to demonstrate that cost‑cutting didn’t come at the expense of patient care. This credibility gap paved the way for standardized performance measurement. In 1990, the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) emerged, creating the widely used HEDIS measures (Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set) to quantify clinical performance. HEDIS allowed employers (aka purchasers) and consumers to compare plans based on quality, in addition to price.

Since most of the quality measures were based on risk-factor medicine (e.g., Controlling BP, Diabetes Control, BMI measurement, etc), the Annual Physical became the perfect visit to collect and document this data. The Annual Physical provided insurers and regulators with a predictable touchpoint to harvest data at scale, effectively transforming the exam into a reporting exercise rather than a clinical one.

The data collected during an “Annual Physical” was then used to prove to purchasers of health insurance, such as employers that their money was being spent well.

Engulfed in Flames

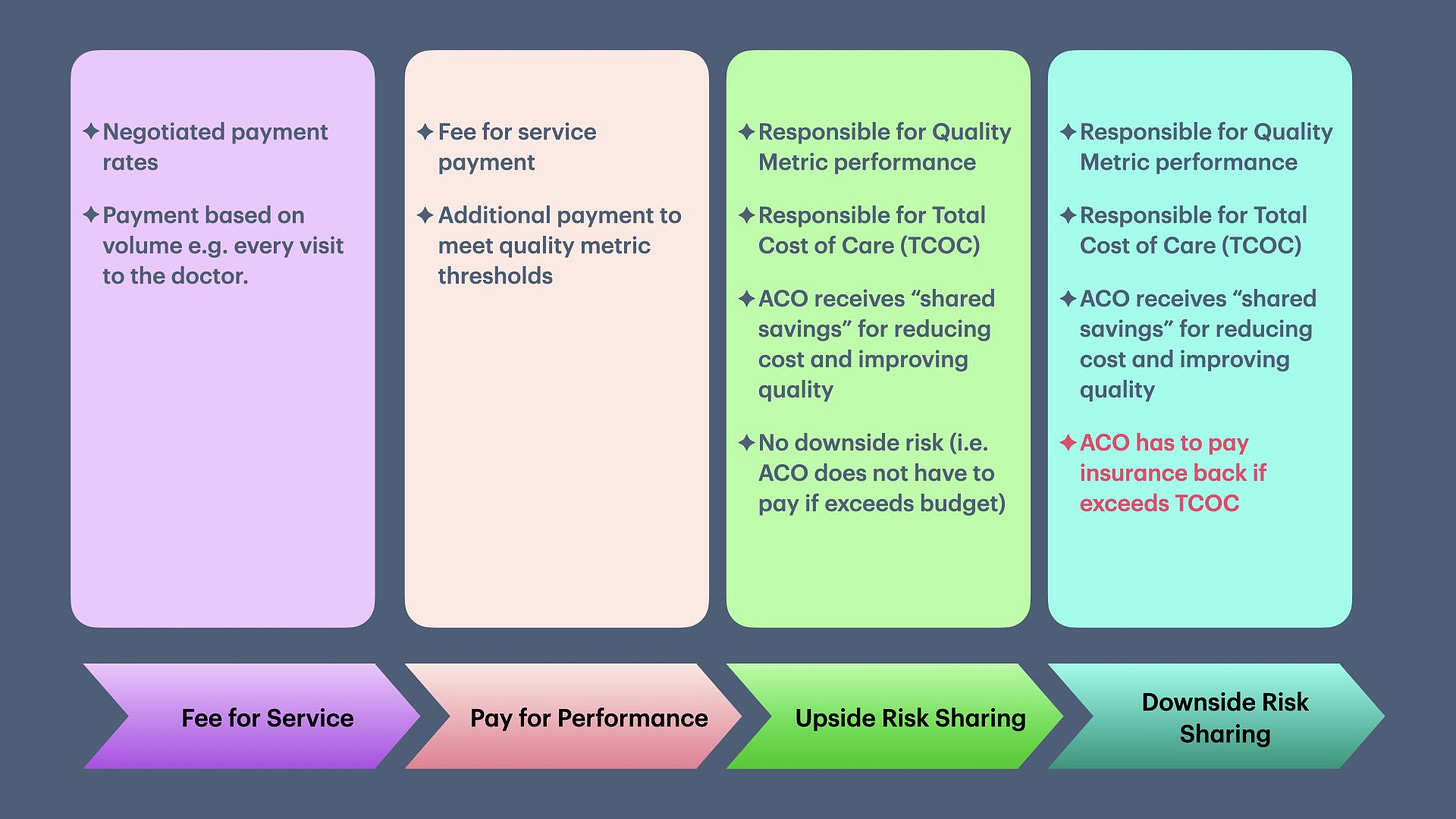

Once collecting data for quality measures became the norm, the next step was to tie quality data to financial incentives, to ensure everyone was getting the best care!

The publication of “To Err is Human”7 and “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century” reframed the U.S. healthcare problem as a failure of quality and accountability. Health plans, employers, and policy makers jumped on the technocratic legitimacy of quality measures and argued that fee-for-service rewarded waste. This manufactured consent paved the way for the Affordable Care Act in 2010.

I covered the history of how quality measurement programs were increasingly tied to financial penalties in my previous article, “Value Based Care & The Illusion of Improvement.” This transformation is summarized in the diagram below.

ACA created Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), and not only tied quality, but also the total cost of care (TCOC) to physician penalties. However, to calculate the TCOC, patients need to be risk-adjusted based on pre-existing conditions and demographics. The Annual Physical, which was already transforming into a “data collection visit” for quality, now also became the vehicle for data collection for actuarial purposes to predict the cost of care.

Even before the passage of the ACA, Pay-for-Performance (P4P) and PQRS in the early 2000s were already starting to strain independent practices. The ACA added fuel to the fire, consuming much of the independent landscape due to the substantial cost and manpower burden of collecting and submitting data. From my prior article, “The Devilish Details of Data Collection:”

To collect and report this data back to insurance companies, PCP offices spent approximately $50,000 in 2014-2015.8 This is why larger organizations with an army of data analysts will always perform better than small medical practices—they have the money and resources to collect and report data.

This burden (along with several others) has pushed many small practices to sell, merge, or close. For physicians, the annual exam became less about patient-physician relationships and more about transferring power from the exam room to corporate data warehouses for profit.

In summary, the Annual Physical has changed the role of the physician from a healer to a diligent record-keeper and risk manager. We have come full circle: the Annual Physical that began as an actuarial analysis for life insurance in the early 20th century has returned to its actuarial analysis roots for Value-Based Care in the 21st.

The Fire Feeds Itself

So, why does the annual exam persist, like a ritual, in the face of minimal evidence? The answer lies at the intersection of medical tradition, cultural expectation, patient psychology, financial incentives, and our litigation-heavy system.

Since the mid-20th century, the annual exam has become a medical tradition and cultural expectation. Doctors recommend the Annual Physical, and patients expect it—we are two peas in the same pod! Not offering Annual Physicals or telling people that these exams have limited benefit is a sure-fire way to lose patients and revenue.

Given our individualistic focus on healthcare, people get a sense of relief when their Annual Physical, with accompanying lab tests are normal. This reassurance carries the weight of science—even if it’s mostly symbolic (technocratic legitimacy).

Next, there are financial incentives, both for doctors and patients. Doctors can bill for the Annual Physical, a recurring income source, while employers offer monetary incentives or penalties to employees for undergoing their yearly physical.

And finally, in our litigation-heavy system, a doctor’s note has become a kind of “get out of jail free card,” transferring risk from the individual/employer to the physician. E.g.:

To call out of work if sick

To apply for FMLA

To prove fitness for work (CDL, police, military)

To join a gym, especially for older people

To keep an emotional-support pet in a no-pet apartment complex

Most of these situations assume the person has an ongoing relationship with a physician who has seen them regularly. In practice, that means having a PCP and showing up for annual visits. Society keeps demanding doctors’ notes, and the easiest way to get one is to maintain the ritual.

Different Cultures, Different Rituals

The United States treats the annual physical as a near-sacred rite. But other wealthy nations have chosen different rituals.

United Kingdom: The NHS offers the NHS Health Check once every five years between ages 40–74, focused narrowly on cardiovascular risk factors. Cancer screenings and immunizations are handled through separate national programs.

Canada: In 1979, the Canadian Task Force on the Periodic Health Examination explicitly recommended against blanket annual exams. Provinces shifted toward “periodic preventive visits” tailored by age and risk, reimbursed every 1–3 years.

Germany: Statutory insurance covers a one-time check-up between ages 18–34, then every three years from age 35. These focus on cardiovascular and metabolic screening, with cancer checks offered separately.

Nordic countries: In Denmark, Sweden, and Finland, there is no culture of annual check-ups for healthy adults. Prevention happens through organized screening programs, child health visits, and opportunistic risk-factor management in primary care. Community-level interventions (diet, smoking, alcohol) are emphasized over yearly exams.

Japan: The outlier. Annual workplace health exams are mandated by law. These exams are exhaustive and include labs and imaging. Yet evidence suggests they generate more utilization than measurable health benefits—a mirror image of the American ritual, but driven by regulation rather than culture.

The Embers of Humanity

For all its flaws, the annual physical is not without value. It offers patients and physicians a chance to talk, get to know each other as human beings, and build trust. Many of the most meaningful conversations in primary care happen not when we are talking about hypertension or diabetes, but about how you spent your weekend. And believe me, these “frivolous” conversations sometimes have a bigger impact on the care we give than your lab values.

But as the Annual Physical becomes more of a data-collection exercise under value-based care, we risk burning away the embers that matter most: the human touch.

Up Next

The American Health system's appetite for data is endless—even if we don’t do anything with it. In the next article, I will look at how & why the system is now set up to force doctors to collect and submit data for the social determinants of health, and then make us accountable for society itself.

Mehrotra, A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Ayanian, J. Z. (2007). Preventive Health Examinations and Preventive Gynecological Examinations in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine, 167(17), 1876–1883. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.167.17.1876

Krogsbøll, L. T., Jørgensen, K. J., & Gøtzsche, P. C. (n.d.). General health checks in adults for reducing morbidity and mortality from disease—Krogsbøll, LT - 2019 | Cochrane Library. Retrieved August 26, 2025, from https://www.cochranelibrary.com/cdsr/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD009009.pub3/full

Krogsbøll, L. T., Jørgensen, K. J., Grønhøj Larsen, C., & Gøtzsche, P. C. (2012). General health checks in adults for reducing morbidity and mortality from disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. The BMJ, 345, e7191. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.e7191

Liss, D. T., Uchida, T., Wilkes, C. L., Radakrishnan, A., & Linder, J. A. (2021). General Health Checks in Adult Primary Care: A Review. JAMA, 325(22), 2294–2306. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.6524

Pathak, R., Giri, S., Aryal, M. R., Karmacharya, P., & Ghimire, S. (2022). Should We Abandon Annual Physical Examination? - A Meta-Analysis of Annual Physical Examination and All-Cause Mortality in Adults Based on Observational Studies. Cureus, 14(7), e26658

Han, P. K. J. (1997). Historical Changes in the Objectives of the Periodic Health Examination. Annals of Internal Medicine, 127(10), 910–917. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-127-10-199711150-00010

Gould, G. M. (1900). A System of Personal Biologic Examinations the Condition of Adequate Medical and Scientific Conduct of Life. Journal of the American Medical Association, XXXV(3), 134–138. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1900.24620290004002

Guyton, G. P. (1999). A Brief History of Workers’ Compensation. The Iowa Orthopaedic Journal, 19, 106–110. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1888620/

Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. (2000). To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System (L. T. Kohn, J. M. Corrigan, & M. S. Donaldson, Eds.). National Academies Press (US). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK225182/

Casalino, L. P., Gans, D., Weber, R., Cea, M., Tuchovsky, A., Bishop, T. F., Miranda, Y., Frankel, B. A., Ziehler, K. B., Wong, M. M., & Evenson, T. B. (2016). US Physician Practices Spend More Than $15.4 Billion Annually To Report Quality Measures. Health Affairs, 35(3), 401–406. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.1258