The Madness of Medication Adherence

The Impossible Mission of Quantifying Medication Compliance

If you hold someone accountable for something they can’t control, you’re not creating accountability—you’re creating burnout.

—My thoughts, rewritten by ChatGPT 40

$100 billion in preventable medical costs per year is attributed to people not taking their medications.1 No wonder many proponents of medication adherence measures argue that if we hold doctors responsible for medication adherence, patient outcomes will improve.

However, as with all quality measures, reality is much more complicated.

Let’s dive in.

The video version of this article is embedded below and available on my YouTube Channel.

The audio podcast and video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

Anatomy Medication Adherence Quality Measures

There are 3 medication adherence quality measures, and they all have the same anatomy:

Measure D08 - Medication Adherence for Diabetes Medications

Measure D09 - Medication Adherence for Hypertension (RAS Antagonists)

Measure D10 -Medication Adherence for Cholesterol (Statins)

The details are in the Medicare 2025 Part C & D Star Ratings Technical Notes PDF document (pages 92-100).

Quality Measure Description

Percent of plan members with a prescription for a medication who fill their prescription often enough to cover 80% or more of the time they are supposed to be taking the medication.

Denominator

Age = 18-75 years

Measure D08 - Prescribed any diabetes medications (except insulin)

Measure D09 - Prescribed RAS antagonists such as ACE inhibitors, Angiotensin Receptor Blockers (ARB), or Direct Renin Inhibitors (DRI)

Measure D10 - Prescribed statins

Numerator

Patients taking the medication for more than 80 percent of the time in the measurement year.

Since people enroll and disenroll in insurance, it is tricky to calculate the measure. Enter the Proportion of Days Covered (PDC), which is calculated as follows (simplified version):

Determine the days’ supply of the medication filled by the patient within the measurement year

This is typically based on prescription refill data.

Determine the total number of days in the measurement period

This is the total number of days in the measurement period, adjusted for insurance coverage, hospitalization, etc.

Apply the formula:

For example, if a patient filled their medication as a 90-day supply, 3 times in the measurement year (i.e., 270 days) with the first fill on Jan 1, then their PDC would be:

Denominator Exclusions

In hospice

ESRD diagnosis or on dialysis

D08 - One or more prescriptions for insulin

D09 - One or more prescriptions for sacubitril/valsartan (Entresto)

Small sample size, i.e., contracts with 30 or fewer enrolled member-years

Reporting Period

Between Jan 1 (or more accurately, the 1st day the patient fills the prescription) and Dec 31.

Data Sources

Prescription Drug Event (PDE) data refers to the records submitted to CMS by Medicare Part D plan sponsors (aka the insurance drug plans) each time a patient fills a prescription.

Rationale for Quality Measure

The rationale is quite obvious—if people don’t take their medications, they are likely to suffer complications from uncontrolled diabetes, hypertension, or high cholesterol, which then will increase the total cost of care.

So, we need to answer the fundamental question: Why don’t people adhere to their medication regimen?

Reasons for Non-Adherence to Medications

Medication adherence is a complex issue with multiple reasons. These reasons can be intentional or non-intentional.2

Intentional Reasons

Patient’s belief system: This can be multifactorial, such as perceived need when the disease is asymptomatic (e.g., hypertension), cultural and/or mistrust in the health system.

Patient choice: E.g., I know it is important, but I am not going to take the medication.

Side effects: Perceived or real side effects. E.g., Fear of erectile dysfunction from beta blockers prescribed after a heart attack.

Cost of medication: This may lead to people not filling prescriptions or skipping days to make the medication last longer

Inconvenience: E.g., working 2 jobs, night shifts, frequent travel

Advertising: People may stop using an older medication (e.g., metformin) as they perceive it to be less effective than new medications (e.g., Jardiance or Ozempic) based on advertising.

Non-Intentional Reasons

Forgetfulness: e.g., dementia, chronic stress

Health literacy: unclear on how to take medication, or getting confused with the medication regimen

Complex medication regimens

Access: Inability to make appointments or no appointments available with physicians for chronic disease management

Poor relationship with provider: e.g., mistrust, communication breakdown

SDOH, including housing instability and food insecurity

The above list is a summary of published literature. If you are a physician, you will quickly realize that many factors are outside your control.

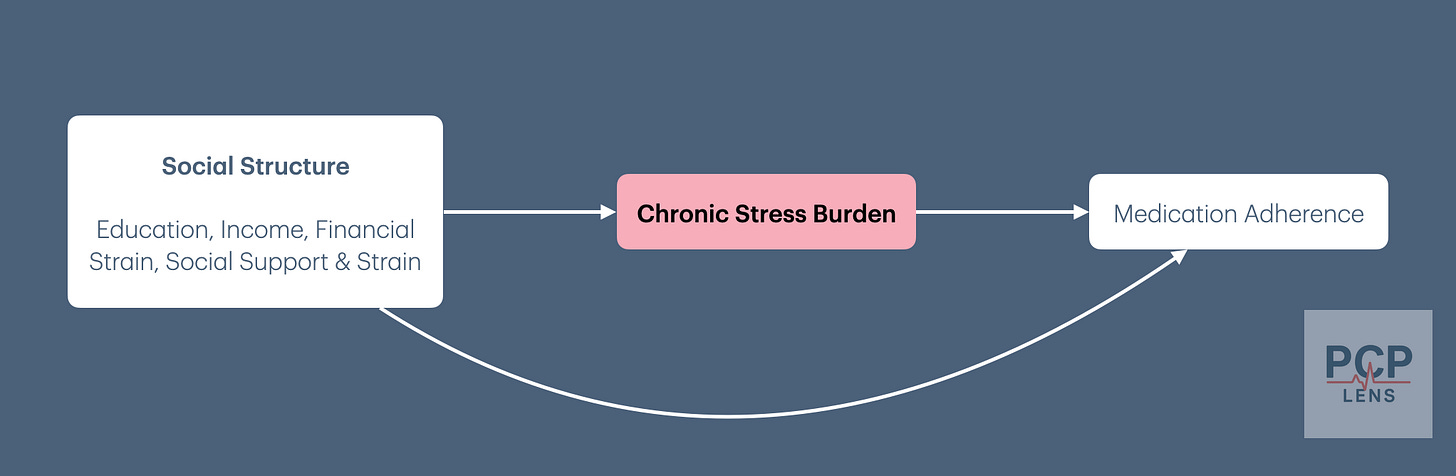

One of the best models for medication non-adherence is the application of “health behavior practiced in a social context.”3 This is illustrated in the diagram below:

The “gold standard” framework for measuring quality is the Donabedian Triad, which looks at three components: Structure, Process, and Outcome. The medication adherence quality measure focuses on the “process”, but the real reason for medication adherence is “structural,” i.e., poor SDOH.4 Creating quality measures under Value-Based Care makes physicians responsible for SDOH, turning doctors into social workers.

Problems With The Quality Measure

Now that we understand the quality measure, let us look at the problems it creates for practicing physicians.

Oversimplification of Complex Human Behavior

Several medical studies assert that medication adherence reduces costs and improves outcomes.5 However, these studies are retrospective and rely on claims data, making them prone to confounding. The most significant confounding factor is that individuals who adhere to their medication regimens are also more likely to follow other treatment plans, which is likely the primary reason for their lower costs and better outcomes.

The reasons why people take or don’t take their prescriptions are complex, as previously mentioned. These quality measures attempt to reclassify human behavior from the complex domain of the Cynefin Framework to the simple domain. Since changing human behavior is hard, most medical institutions rely on gamifying the statistics to improve performance—Goodheart’s Law. The change in workflow to improve the statistic then increases the complexity of medical workflows, making the system more dangerous and prone to errors—Charles Perrow’s theory of Normal Accidents.

Filled Vs Consumed

The Proportion of Days Covered (PDC) measure offers a convenient and readily available metric. However, it operates under the assumption that filled prescription data translates directly to medication consumption.

Under the 2025 CMS Star Measures (PDF Link), over 90% of patients must have a PDC of 80% or higher for a health plan to receive a 5-star rating. That is a high bar.6

The dependence on “fill rate” and massive market/profit opportunity for health plans that achieve 5-star status opens up the measure for gamification under Goodheart’s law. Insurance plans and providers are incentivized to issue longer prescriptions, such as 90-day or, more recently, 100-day refills, to improve prescription fill rates.

E.g., a 100-day prescription with 2 refills (i.e., 300 days) allows health plans to qualify for the numerator.

The incentive to promote longer prescriptions to achieve CMS 5-Star measure has created several unintended consequences for doctors:

Pharmacies and health plans often refuse to fill prescriptions for shorter time frames, e.g., 30 days, when doctors are titrating doses of medications.

This increases the financial burden on patients as they end up paying for medications they don’t need.

Paradoxically, this may delay the titration of medications, leading to worse outcomes.

People are confused as they have extra pill bottles and are unsure which ones they should take, leading to medication errors.

People with extra medications end up sharing (or selling) them with family members, who then don’t fill their medications and appear non-compliant.

These longer prescription requests are not limited to the medications covered by the quality measures, but to all chronic medications. E.g., I generally start an SSRI for 1 month for new onset anxiety/depression and titrate to effect. However, I routinely get requests from pharmacies to convert the 30-day supply to a 90-day supply!

Wastage of unused medication that probably ends up in the water supply.

It is a well-known strategy among doctors to “hold prescriptions hostage” if people don’t come for their scheduled appointments. This is due to several reasons, including:

Ensuring that the medication dose is still appropriate and that chronic diseases are controlled.

Ensuring the patient does not experience side effects, some of which can only be detected through lab tests, such as high potassium from RAS Antagonists or liver failure from Statins.

Fear of medical malpractice—patient or family member suing the doctor as they did not perform due diligence in monitoring chronic disease and medication side effects.

A common strategy is to prescribe a 30-day supply to allow patients to continue medications but give them time to schedule an appointment with the doctor. When health plans require doctors to prescribe a 90-day supply by refusing to cover shorter durations, they impair doctors’ ability to monitor chronic diseases and side effects from medications.

Penalties When Switching Medication Classes

Under these quality measures, physicians are penalized when switching medications from one class to another. For example:

Measure D09: If a blood pressure medication is switched from a RAS antagonist (e.g., lisinopril or valsartan) to a different class (e.g., hydrochlorothiazide or amlodipine), even if the patient's blood pressure improves.

Measure D10: If statins are discontinued due to intolerance or switched to another cholesterol-lowering medication (e.g., ezetimibe).

Cost of Medications

Medication cost is a significant barrier for some people. People may choose to skip doses to try to “make the prescription last longer,” procure medications from family/friends, obtain samples from their doctor, or, if they have the ability, purchase the medicines from a foreign country. For e.g., I have several patients who routinely travel to India and will often purchase their medications there as they are cheaper, but I get dinged on the quality measure!

To make matters worse, sometimes prescription medications are more expensive to buy through insurance than to pay cash outright. These “cash payments” are not captured in the administrative data, which has the unintended (or intended to increase payor profits) effect of forcing patients to buy medications using their insurance.

If people buy their medications without going through insurance (i.e., cash pay) or from another country, the PCP/ACO and health plan are penalized.

Patient Selection Bias

In my last article on “The Pressure to Control Blood Pressure,” I wrote:

The “Controlling Blood Pressure” quality measure penalizes doctors trying to manage populations with poor SDOH, e.g., the homeless, those with low health literacy, or those who distrust the health system, which is the entire reason for creating this quality measure.

The same is true for the medication adherence quality measures. Patients who struggle to take their medications due to SDOH will lead to their PCP looking “worse on paper.” Due to the financial penalties attached to these quality measures, some of these people may end up being discharged from their PCP practices, who may then end up in the ER with complications.

Now that we understand some of the problems with the Medication Adherence Quality Measure, let's consider ways we can increase performance.

Improving Performance On Medication Adherence Quality Measure

A more appropriate title would be, The Futility of Improving Performance Within a Flawed System.

The short answer is—not a whole lot in private practice, where doctors generally already have good relationships with their patients.

The longish answer is:

Educate

Simplify the medication regimen if possible

Use pill boxes or reminder tools

Review refill history in EHR

Create workflows so that prescriptions are filled in a timely fashion when prescribers are on leave

Ask about SDOH, especially if the cost of medication is a problem

If the patient cannot afford medication, have a list of resources to give them so that they can procure medication

This may still penalize the doctor if the “prescription fill” data is not reported to the health plan

Prescribe a 100-day supply with 2 refills if appropriate (i.e. 300-day supply)

Use a pharmacist if you have access to one

Conclusion

As with all quality measures, the unintended consequences of medication adherence quality measures likely outweigh any potential benefits. Furthermore, quality measures are typically part of value-based contracts in which PCPs are forced to participate.

Essentially, we have created a system in which PCPs are asked to control complex human behavior and address SDOH without any resources or tools—under the threat of payments being withheld under value-based care.

Up Next

Every quality measure sounds great as a political slogan, but falls apart on scrutiny. I could keep writing about each individual quality measure, but I would just be beating a dead horse. I will, though, revisit health quality from a different perspective in future articles.

In the interim, if you missed any of the quality articles, you can find them here: PCP Lens Quality Articles.

In the next article, I will discuss a fun little topic—why fax still persists in healthcare, and the monopoly that might replace it.

Kleinsinger, F. (2018). The Unmet Challenge of Medication Nonadherence. The Permanente Journal, 22, 18–033. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/18-033

Hugtenburg, J. G., Timmers, L., Elders, P. J., Vervloet, M., & van Dijk, L. (2013). Definitions, variants, and causes of nonadherence with medication: A challenge for tailored interventions. Patient Preference and Adherence, 7, 675–682. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S29549

Oates, G. R., Juarez, L. D., Hansen, B., Kiefe, C. I., & Shikany, J. M. (2020). Social Risk Factors for Medication Nonadherence: Findings from the CARDIA Study. American Journal of Health Behavior, 44(2), 232–243. https://doi.org/10.5993/AJHB.44.2.10

Adeoye-Olatunde, O. A., Hastings, T. J., Blakely, M. L., Boyd, L., Aina, A. B., & Sherbeny, F. (2025). Social Determinants of Health and Medication Adherence in Older Adults with Prevalent Chronic Conditions in the United States: An Analysis of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2009–2018. Pharmacy, 13(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy13010020

Wilder, M. E., Kulie, P., Jensen, C., Levett, P., Blanchard, J., Dominguez, L. W., Portela, M., Srivastava, A., Li, Y., & McCarthy, M. L. (2021). The Impact of Social Determinants of Health on Medication Adherence: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 36(5), 1359–1370. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-020-06447-0

Campbell, P. J., Axon, D. R., Taylor, A. M., Smith, K., Pickering, M., Black, H., Warholak, T., & Chinthammit, C. (2021). Hypertension, cholesterol and diabetes medication adherence, health care utilization and expenditure in a Medicare Supplemental sample. Medicine, 100(35), e27143. https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000027143

Williams, J. L. S., Walker, R. J., Smalls, B. L., Campbell, J. A., & Egede, L. E. (2014). Effective interventions to improve medication adherence in Type 2 diabetes: A systematic review. Diabetes Management (London, England), 4(1), 29–48. https://doi.org/10.2217/dmt.13.62

Farley, J. F., & Urick, B. Y. (2021). Is it time to replace the star ratings adherence measures? Journal of Managed Care & Specialty Pharmacy, 27(3), 399–404. https://doi.org/10.18553/jmcp.2021.27.3.399