Health Determinants at Check-In

Funneling Social Problems into the Exam Room

“Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing but medicine on a large scale.”

—Rudolf Virchow

If you hold someone accountable for something they can’t control, you’re not creating accountability—you’re creating burnout.

This is the 6th & final article in my series, “Healers to Healthkeepers.”

In previous articles, I traced how American healthcare transformed from a system focused on collective public health infrastructure into one centered on individual clinical accountability—from 19th-century sanitation reforms through postwar hospital financing, risk-factor medicine, and quality measurement systems. We’ve not only created the cultural hegemony that doctors are the “keepers of health,” but also built the infrastructure to document & code the healthcare status of the population to report to the financiers of healthcare. E.g., ICD-10 code for diabetes with a CPT-II code to indicate that diabetes is under control.

Since the strongest predictors of health are social, it was only a matter of time before the financiers asked doctors to screen for the Social Determinants of Health (SDOH).

This article looks at how technocratic legitimacy—the use of objective-seeming measures to mask political choices—is transforming social problems into clinical responsibilities.

To be clear: social factors should inform clinical decisions. But, rather than invest in housing, food security, and economic stability, we now demand that doctors screen for their absence. The result is a system that appears accountable on paper while making the actual work of healing harder.

Let’s dive in.

The video version of this article is embedded below and available on my YouTube Channel.

The audio podcast and video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

SDOH Enters the Clinic

For years, global and national public health bodies like the WHO and CDC championed the SDOH framework, but it remained largely in the domain of policy papers and academic conferences. The migration of the SDOH framework into clinical settings accelerated in the 2000s through a convergence of policy, payment reform, and technocratic measurement.

The 2001 Institute of Medicine report, Crossing the Quality Chasm, established the framework by defining quality not just as clinical outcomes, but as care that is “patient-centered.” This term was elastic enough to eventually encompass patients’ entire social context. Initially, “patient-centered” meant respecting patient preferences in treatment decisions. Within a decade, it expanded to include cultural competence, then health literacy, and finally, by the 2010s, addressing patients’ social circumstances. The term’s flexibility made it the perfect vehicle for expanding clinical responsibility.

In 2008, the WHO Commission on Social Determinants of Health formalized what public health had long known: that health is primarily determined by conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age. The question then became — who would be responsible for addressing SDOH?

The answer came with the passage of the ACA in 2010, which created Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs), making doctors financially responsible for the total cost of care (TCOC). Under these contracts, if an ACO’s patients cost more than projected, the physician groups absorb the financial loss—sometimes millions of dollars. Conversely, keeping costs below projections means shared savings. Since unmet social needs drive expensive ER visits and hospitalizations, ACOs have a direct financial incentive to identify and address these social factors.

So, what began as a best practice for safety-net hospitals—screening vulnerable patients for unmet social needs—has become an economic necessity under value-based contracts.

This economic necessity was solidified by the National Academy of Medicine (NAM)1 in 2014. Not only did NAM issue recommendations for the clinical collection of social and behavioral data, but it also framed them as essential data elements for achieving health equity and improving population health.

NAM’s fundamental mistake was operationalizing the data collection process through individual clinical encounters—a setting designed for diagnosing and treating disease, not for redistributing resources or building infrastructure. It’s like asking a firefighter to prevent fires by documenting which neighborhoods lack fire codes, then holding them accountable when those neighborhoods burn.

CMS followed up by developing standardized screening tools called Health Related Social Needs (HRSN). CMS then incorporated these HRSN screening tools into quality measures—first for hospitals (2024), and for outpatient settings (2026). CMS also embedded HRSN performance into Medicare Advantage Star Ratings, tying billions in bonus payments to documentation of patients’ social conditions.

In Value-Based contracts, since patient attribution is based on PCP panels, the documentation burden of collecting and reporting HRSN data has fallen to PCPs.

But how do these policy mandates actually function in clinical encounters? The answer lies in a crucial linguistic transformation that makes social problems appear medical.

The Words That Shift Blame

To operationalize this new SDOH screening policy push, the system needed a standardized language to make complex human suffering “legible” to a bureaucracy.

Some of you may have noticed that I switched from using the term SDOH to HRSN (Health-Related Social Needs) in the prior section! This quiet replacement of SDOH with HRSN makes it possible to shift accountability:

Social Determinants of Health (SDOH): Implies societal responsibility & requires policy solutions.

E.g., “Homelessness increases cardiovascular disease” is an SDOH statement—it points to a policy failure requiring legislative action.

Health-Related Social Needs (HRSN): Implies individual needs & requires clinical assessment and intervention.

E.g,. “Mrs. Jones screens positive for homelessness” is an HRSN statement—it points to an individual problem requiring clinical documentation and referral.

The underlying issue is the same, but there are radically different implications for who is responsible for fixing it. SDOH asks, “What policies have failed?” HRSN asks, “Which patients need help?” The first demands systemic change. The second demands clinical action.

Once the language existed to individualize SDOH as HRSN, the next step was to measure it within a clinical encounter. Enter the ICD-10 Z-codes. These codes have existed for decades, originally intended to capture ‘factors influencing health status’—things like family history or vaccination status. But codes for social conditions (homelessness, food insecurity, inadequate housing) were rarely used because physicians had no financial reason to document them. Under value-based care, that changed. Now, these dormant codes are becoming mandatory screening tools, transforming the purpose of the clinical encounter itself.

Examples include:

Z59.0 - Homelessness

Z59.1 - Inadequate housing

Z59.4 - Food insecurity

Z59.7 - Insufficient social insurance and welfare support

Z60.2 - Problems related to living alone

Z62.8 - Problems related to upbringing (lack of adequate supervision)

Z63.4 - Disappearance or death of a family member

Z65.0 - Conviction in civil and criminal proceedings without imprisonment

The logic of measuring individual HRSN appears compassionate. How can you manage diabetes if your patient has nowhere to store insulin? But, Z-codes don’t create housing or food; they only create documentation of their absence.

Changing the language allows the exam room to become a census bureau for social failure, with physicians as reluctant clerks who record conditions they cannot treat.

Therefore, the language of HRSN and Z-codes provide the technical means to transfer SDOH from the policy domain to the clinical domain. The end result: medicalization of social failure.

Food for thought: Policy vs Clinical Dilemma

This mismatch between SDOH as a political choice vs HRSN as a clinical diagnosis forces a fundamental question about where responsibility should lie:

Should your PCP be responsible for paying for a refrigerator to store insulin to control diabetes?

Should health plans, such as Medicaid (created to pay for healthcare) be paying for housing (e.g., under Medicaid 1115 HRSN waivers)?

This is exactly what we’re building. We’ve just hidden the absurdity behind acronyms: ACO, VBC, SDOH, and HRSN.

Screening Without Solutions

Value-Based Care (VBC) is a concealed effort to build a social safety net inside the only system America is still willing to (reluctantly) fund: medicine.

Having defunded public health and social services for decades, policymakers now use VBC’s financial incentives to force healthcare to absorb these abandoned responsibilities. It is a policy of abdication, and of laundering political failure through the language of “population health.”

This systemic bait-and-switch fundamentally redefines the physician’s role. Value-based care repurposes our clinical expertise for social surveillance. The expectation is no longer just to diagnose hypertension, but to uncover the housing instability driving it, document it to increase the risk score, and then “fix it,” under threat of financial penalties.

PCP Rant of how this looks like in practice:

Mrs. Jones, a 58-year-old woman with diabetes with a HbA1c of 9.2% screens positive for inadequate housing. She does not have a place to store her medications, which is why she cannot take them consistently, leading to uncontrolled diabetes.

In my 15-minute encounter, even if I can find a housing program, help fill out all the referral forms, there is still, on average, a 1-2 year waitlist to get accepted.

However, next quarter, my quality report will flag Mrs. Jones’ uncontrolled diabetes as my performance gap.

And if I have enough patients like Mrs. Jones in my panel, I am financially penalized for not meeting quality measures under VBC contracts, even after doing everything I could.

End Rant

The system creates accountability without capacity, demanding that doctors solve problems that require billions in social investment with referral lists and good intentions. We hold physicians responsible for outcomes they cannot influence, and then wonder why we have difficulty finding doctors!.

Medical Abundance, Social Scarcity

As much as we complain about the cost of healthcare, and even access to healthcare, the fact remains that we have medical abundance coupled with social scarcity. Our system will pay for a 3rd line chemotherapy treatment, which may (or may not) improve life expectancy by a few months,2 but refuses to invest in SDOH.

For example, permanent supportive housing for chronically homeless individuals costs $15,000-20,000 annually and returns a median of $1.8 for every $1 spent through reduced ER visits and hospitalizations.3 Meanwhile, managing the same individual’s health crises through emergency departments costs $40,000-$60,000 annually with no upstream impact.4

This “social-to-clinical” (i.e., SDOH to HRSN) funnel is the direct consequence of a decades-long political choice: to inflate the medical-industrial complex while starving the social safety net.

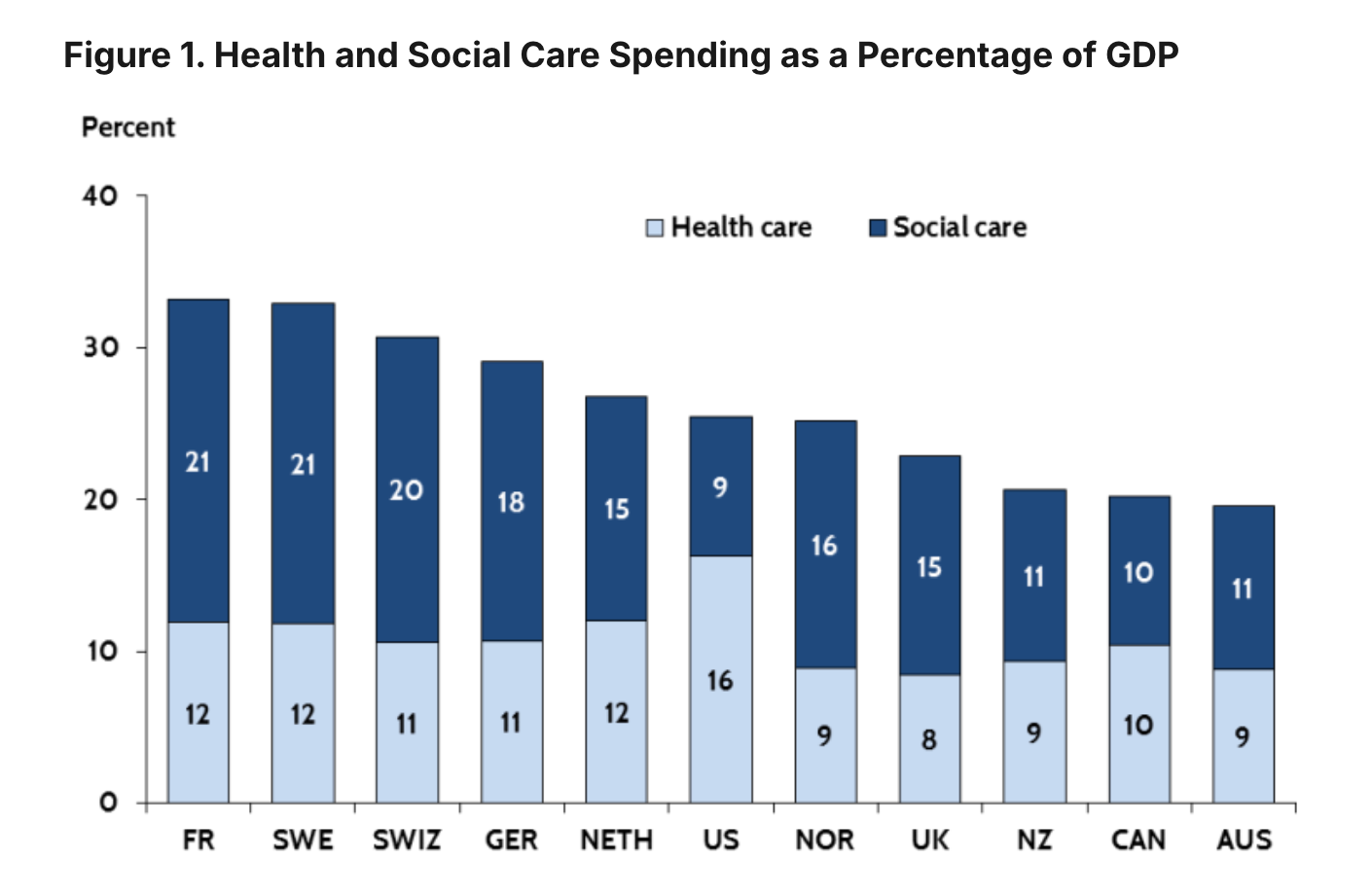

The United States is a global outlier in its spending priorities. We spend over 17% of our GDP on healthcare, nearly double the average of other wealthy nations, yet we achieve worse health outcomes.5 This paradox is explained by what we don’t spend on. While our peer countries spend about $1.70 on social services for every dollar they spend on health, the U.S. spends just 56 cents.6 This difference in spending priorities translates into fundamentally different infrastructure.

For example, the UK employs over 3,500 “social prescribing link workers” who connect patients to housing, food, and social services—outside of clinical visits. When a British patient struggles with housing, they see a navigator, not their GP. Early evidence shows promise: one evaluation found a 40% reduction in GP appointments, and economic analysis suggests a return of £3.42 for every £1 invested. The model works by addressing social determinants through dedicated social infrastructure rather than clinical documentation.7

The UK can afford this approach because of how they allocate resources. The contrast with American spending priorities is stark, as illustrated by the graph below.

Here in America, the cost of SDOH/HRSN in the national balance sheet is written into every clinical encounter. It’s the absurdity of sitting in a technologically advanced clinic, surrounded by medical abundance, while the only tool we have for a patient’s hunger is a Z-code. The system will not only pay tens of thousands for the downstream consequences of social failure (e.g., ER visits, hospitalizations), but under VBC also penalize doctors for failing to document these conditions.

The Choice We Refuse to Make

The root cause of chronic disease is not clinical failure.

It is a policy failure to address clinical symptoms. The irony is that we recognized and fixed similar problems in the 19th century, but are refusing to do it in the 21st.

Instead, we’ve turned the determinants of health into clinical HRSN tasks: screen & document. That’s accountability without authority.

Let’s think about what HRSN accountability looks like in practice:

A chronically homeless patient with COPD cycles through three ER visits and two hospital admissions in six months with a total cost of approx $120,000. During each visit, doctors code his housing instability (Z59.0) and a social worker refers him to a shelter program. Each time, he’s discharged back to the street. Eventually, he qualifies for permanent supportive housing with an approx annual cost of $18,000. His ER visits drop to zero. His COPD stabilizes. We knew this would work. We just made him wait until he was sick enough to justify the investment.

If we want fewer diseases, we have to change what makes people sick: stable housing, living wages, reliable transit, and funded public health infrastructure. Those are legislative choices, not clinical workflows. Until we invest in the health determinants themselves, we’ll keep mistaking documentation for remedy—and the burden of chronic disease will grow, whatever the Z-code.

And, even if HRSN ends up helping people, it will only help after people fall sick. We are back to paying for sickness, instead of keeping people healthy.

Up Next

Going into the new year, I still have plenty of ideas of what else to cover.

In the meantime, I will be taking a few months off. I am planning to get back to publishing sometime in February/March 2026.

Happy Holidays.

The National Academy of Medicine was formerly known as the Institute of Medicine (IOM)

Salas-Vega, S., Iliopoulos, O., & Mossialos, E. (2017). Assessment of Overall Survival, Quality of Life, and Safety Benefits Associated With New Cancer Medicines. JAMA Oncology, 3(3), 382–390. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4166

Jacob, V., Chattopadhyay, S. K., Attipoe-Dorcoo, S., Peng, Y., Hahn, R. A., Finnie, R., Cobb, J., Cuellar, A. E., Emmons, K. M., & Remington, P. L. (2022). Permanent Supportive Housing With Housing First: Findings From a Community Guide Systematic Economic Review. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 62(3), e188–e201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.08.009

Larimer ME, Malone DK, Garner MD, et al. Health Care and Public Service Use and Costs Before and After Provision of Housing for Chronically Homeless Persons With Severe Alcohol Problems. JAMA. 2009;301(13):1349–1357. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.414

Health expenditure per capita: Health at a Glance 2023. (2023, November 7). OECD. https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/health-at-a-glance-2023_7a7afb35-en/full-report/health-expenditure-per-capita_735cda79.html

NHE Fact Sheet | CMS. (n.d.). Retrieved October 21, 2025, from https://www.cms.gov/data-research/statistics-trends-and-reports/national-health-expenditure-data/nhe-fact-sheet

Re-balancing medical and social spending to promote health: Increasing state flexibility to improve health through housing. (n.d.). Brookings. Retrieved October 21, 2025, from https://www.brookings.edu/articles/re-balancing-medical-and-social-spending-to-promote-health-increasing-state-flexibility-to-improve-health-through-housing/

There is another apples-to-oranges comparison of Public health spending between the US and other OECD countries. The US budgets bioterrorism-related spending under Public Health, which is a significant amount. Other OECD countries budget this under defense.

NASP. (n.d.). The future of social prescribing in England—National Academy for Social Prescribing. NASP. Retrieved October 21, 2025, from https://socialprescribingacademy.org.uk/resources/the-future-of-social-prescribing-in-england/

Brilliant framing of the linguistic sleight of hand here. The SDOH to HRSN shift is dunno, almost like renaming "poverty" to "underresourced lifestyle choice" so we can code it. What's wild is that Z-codes basically turn physciains into compliance officers for social policy failure without giving them any actual budget authority or interventiontools.

Really great piece. I’m seeing this in the VBC orgs I work with (where clinics are being asked to operationalize social risk at a depth they were never designed for) I used to think of VBC as a clinical organization with a social care arm, but I’m starting to wonder if the end state is actually a care navigation and social care organization with clinical escalation capacity. It would be much simpler if social care did not need to be veiled in a clinical guise to be seen as legitimate, but given the political stigma around social care in the US, VBC may be the most workable vehicle we have right now to deliver the kind of support people actually need.