Rethinking Quality of Colon Cancer Screening

Balancing hope, fear, and evidence in colorectal cancer prevention

Hope and fear shape the landscape of modern medicine, but those forces are not always benign. Hope drives us to invest in cancer screenings, promising a healthier future. Yet the medical-industrial complex, capitalizing on fear and promoting the specter of death, can skew those efforts towards overdiagnosis and overtreatment in the pursuit of profits, leaving a trail of harm in the wake of progress.

My thoughts, rewritten by ChatGPT

With that introduction, let’s dive into Colorectal Cancer Screening.

(Standard Disclaimer: The information below is NOT medical advice.)

The video version of this article is embedded below and available on my YouTube Channel.

The audio podcast and video versions are also available on the Podcasts Page.

Anatomy of Colorectal Cancer Screening Measure

Quality Measure Description

Percentage of adults 45-75 years of age who had appropriate screening for colorectal cancer.

Denominator

Everyone between Age 46-75 years of age

Numerator

This includes patients with one or more tests to screen for colorectal cancer. Appropriate screenings include:

Fecal occult blood test (FOBT) during the measurement period

Stool DNA (sDNA) with FIT test during the measurement period or the two years prior to the measurement period

Flexible sigmoidoscopy during the measurement period or the four years prior to the measurement period

CT Colonography during the measurement period or the four years prior to the measurement period

Colonoscopy during the measurement period or the nine years prior to the measurement period

Denominator Exclusions

Enrolled in hospice or palliative care

Death during the measurement year

Diagnosis or past history of colorectal cancer.

66 and older and living long-term in a nursing home

66 and older who meet criteria for BOTH Frailty AND advanced illness as defined by specific codes.

Reporting Period

Valid patient encounter between Jan 1 and Dec 31.

Data Sources

CMS has switched to electronic clinical quality measure (eCQM) for colon cancer screening reporting, which uses billing codes (CPT and ICD-10) in the eCQM logic. As far as I know, most eCQMs allow for supplemental data, but how that will work in practice in the 2025 reporting year is up in the air.

I published a primer on eCQM in my prior article, “The Devilish Details of Data Collection.”

Rationale for Quality Measure

The rationale for Colorectal cancer screening QM is based on the 2021 USPSTF guidelines, which recommend screening individuals 45-75 years of age who are at average risk for colorectal cancer.1

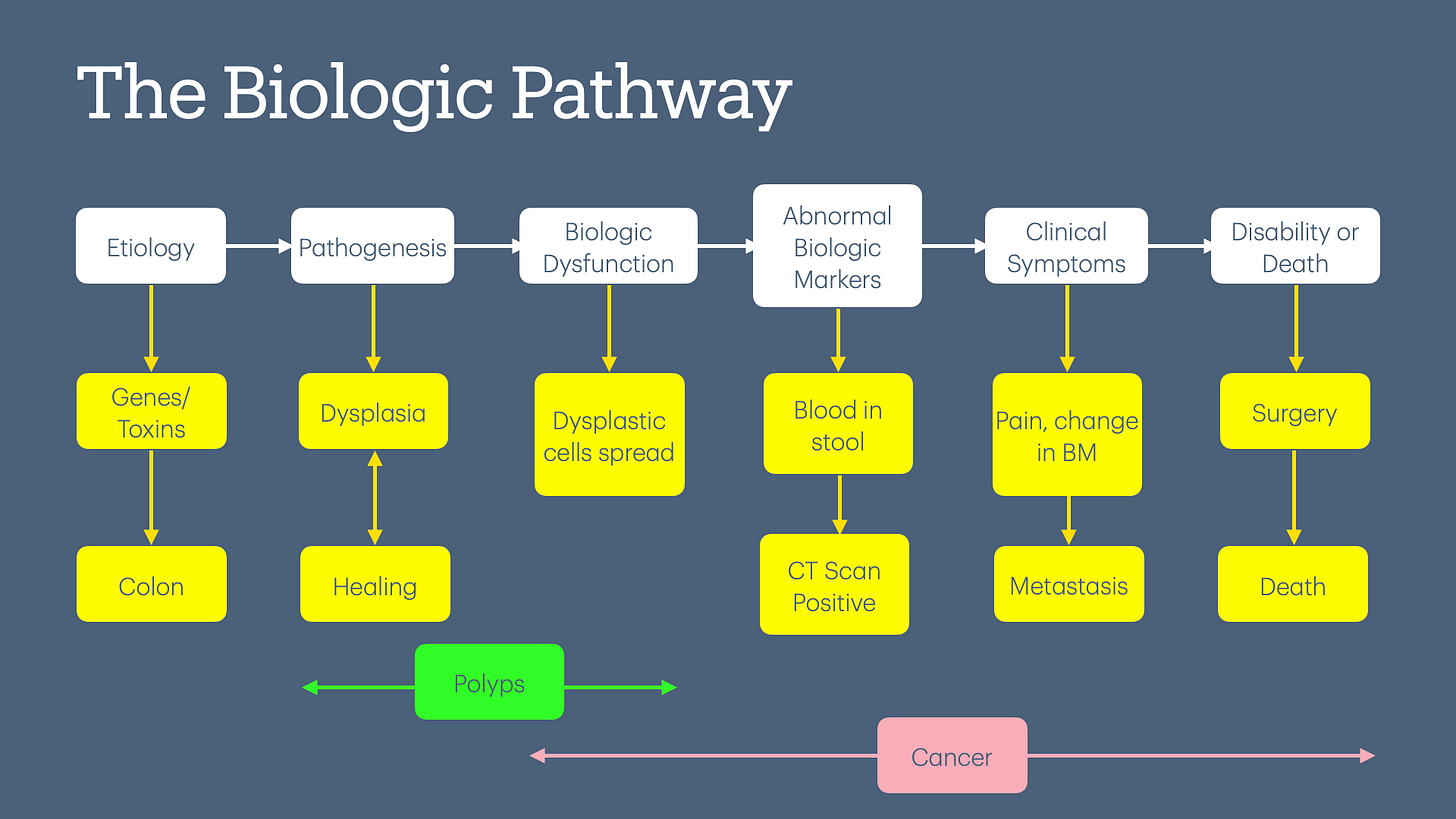

The physiologic basis of colon cancer screening is based on the adenoma-carcinoma sequence. This theory posits that all colon cancers start with a polyp, progress to breach the colon wall, spread to other organs, and eventually cause symptoms, including death.

Interestingly, the guidelines don’t define low risk. Therefore, the way the guidelines are written, everyone needs colon cancer screening unless they are in the denominator exclusion criteria (e.g., already have a diagnosis of colon cancer).

How Do We Define Colorectal Cancer?

Before we look at the data behind colorectal cancer screening, we need to define colorectal cancer. The standard definition of any cancer is “uncontrolled growth of cells,” but that raises the question, “At what point in the lifecycle do we decide that the growth is uncontrolled?”

To make matters more complicated, we can look at this definition from two lenses:

Natural history of progression of disease (backward-looking): If we start with symptomatic metastatic colon cancer, then we will attempt to define any polyp or dysplastic colon cells as either cancerous or pre-cancerous.

Biologic pathway (my preferred and forward-looking term): If we start with normal wear and tear of the colon wall, which leads to the production (and destruction) of dysplastic cells and even polyps, then the definition becomes a lot harder.

Is every polyp going to spread and/or cause symptoms? If they spread, how long will it take the polyp to spread—months, years, or decades?

What level of dysplasia needs to be present to define pre-cancer?

What level of spread should be present to define colon cancer?

How we define colorectal cancer will determine its incidence rate and 5-year survival rates due to lead time bias. In other words, if we define cancer earlier in the pathway, screening tests will appear to save lives!

A Mini-Critical Look at USPSTF Guidelines

The quotes in the sections below are directly from the 2021 USPSTF guidelines, with my thoughts below.

FOBT

Trials that report on colorectal cancer outcomes with high-sensitivity FOBT screening are currently lacking, although several older trials report decreased colorectal cancer mortality with Hemoccult II screening (an older gFOBT no longer commonly used).

Interpretation: The new tests (e.g., FIT) are more sensitive, which increases the chances of a false positive rate.2 This higher false positive rate may erase the benefits of colorectal cancer screening documented in older clinical studies and possibly cause harm.

Sigmoidoscopy

Pooled results from 4 RCTs… on flexible sigmoidoscopy compared with no screening show a significant decrease in colorectal cancer mortality… over 11 to 17 years of follow-up.

Interpretation: Sigmoidoscopy is the only colon cancer screening test that has shown a reduction in both cancer-specific mortality and all-cause mortality3—although after a single sigmoidoscopy.4 The challenge is that most of these trials were approximately 25 years ago, and medical treatment has improved since then. However, this is a moot point for sigmoidoscopies, as no one performs this test today due to insurance reimbursement challenges.5

Stool DNA

A total of zero studies have examined the mortality benefits of stool-based DNA tests for colon cancer screening. These tests have been approved based on their concordance with finding either colon cancer or advanced “pre-cancerous” polyps on colonoscopy. Essentially, these tests tell us the sensitivity/specificity of the test based on the “gold standard colonoscopy.” Those of you who are statistically inclined will realize that the real-world performance of stool-DNA tests depends on incidence and will result in a high false positive rate in low-risk populations.

So, if the studies compare stool DNA tests against the gold standard, colonoscopy, let’s look at what USPFTF says about colonoscopy.

Colonoscopy

Two prospective cohort studies (n = 6,927) in US-based populations reported on colorectal cancer outcomes after colonoscopy screening. One study among health professionals found that, after 22 years of follow-up, colorectal mortality was lower in persons who reported receiving at least one colonoscopy.

…

Another cohort study among Medicare beneficiaries reported that the risk of colorectal cancer was significantly lower in adults aged 70 to 74 years (but not in those aged 75 to 79 years) eight years after receiving a screening colonoscopy.

Interpretation: The USPSTF Grade A recommendation to perform colonoscopies in all adults aged 50-74 is based on the two cohort studies quoted above. The decision to lower the age to 45 was based on CISNET data modeling, i.e., we don’t have any real-world studies in the 45-49 age group about the benefits of colon cancer screening.

And what do we get after all these screenings? Per CISNET modeling:

This finding translates to an estimated 104 to 123 days of life gained per person screened.

The above statement is a statistical generalization as there will be a lucky few people who will live for decades, while in others, colonoscopy will not make any difference.

NordICC Trial

The NordICC Trial6 is the only randomized controlled trial to assess whether colonoscopy saves lives. Let’s look at the conclusion first:

The risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was lower among participants who were invited to undergo screening colonoscopy than among those who were assigned to no screening.

Just reading the conclusion, one might think that colonoscopy saves lives. But let’s dig a little deeper. This is what the authors mean by the above statement:

In intention-to-screen analyses, the risk of colorectal cancer at 10 years was 0.98% in the invited group and 1.20% in the usual-care group, a risk reduction of 18%.

In other words, the absolute risk reduction (ARR) in finding colon cancer was 0.22% (1.20% - 0.98%) in 10 years. However, here is the kicker:

The risk of death from colorectal cancer was 0.28% in the invited group and 0.31% in the usual-care group (risk ratio, 0.90; 95% CI, 0.64 to 1.16).

…

The risk of death from any cause was 11.03% in the invited group and 11.04% in the usual-care group (risk ratio, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.96 to 1.04)

Translation: Colonoscopy offered no benefit either in decreasing colon cancer-specific mortality or all-cause mortality.

While discussing the details of the NORDICC trial is beyond the scope, the American Gastroenterology Association (AGA) published a scathing takedown of the trial,7 and other authors published a scathing takedown of AGA’s position.8 For readers looking to learn more about NordICC trial, I would recommend this excellent breakdown at Sensible Medicine, “Screening Colonoscopy Misses the Mark in its First Real Test.”

Now, we have 2 cohort studies showing benefit (per USPSTF guidelines) vs. 1 RCT showing no benefit of colonoscopy. Furthermore, there are zero good-quality studies showing a reduction in all-cause mortality. The reason we need to measure all-cause mortality is because we fail to capture deaths caused by the screening test itself, as illustrated in the diagram below.

In my opinion, we should offer colonoscopies based on the individual's risk of colon cancer and not conduct population-based screening. This would not only decrease the risk of harm in low-risk people but would also save a boatload of money.9

And, it definitely should NOT be a quality measure because once it becomes a quality measure, Goodheart’s law applies, leading to harm.

(I have omitted data on colorectal cancer screening provided by other American societies and other countries, as including it would exceed the email's length limit.)

Now that we understand the data behind the quality measure, let’s dive into how colon cancer screening quality measures work in real life and how they can cause harm.

Problems with Colon Cancer Screening Quality Measure

In my last article, “False Positives, Real Profits,” I wrote:

There are statistical techniques that can give the appearance of efficacy to a test when, in fact, the test is completely useless.

These techniques include over-diagnosis bias, lead time bias, and length time bias. For an overview of these techniques, please see my previous article (I promise it is not technical or math-heavy). All of these statistical techniques apply to colon cancer screening studies.

Why is everyone at average risk?

The clinical studies showing the benefit of colorectal cancer screening were done predominantly in American Caucasians. However, the United States has a large immigrant population, with many immigrating later in life. Most immigrants have a genetic, cultural, and dietary profile different from the traditional American Caucasian population; therefore, their risk for colorectal cancer is different. For example, many American Indians (the ones who immigrated from India) traditionally are vegetarian and rarely, if ever, eat processed meat—a known carcinogen (I belong to this category). Yet, USPSTF applies the same rules for colorectal cancer screening to everyone!

Furthermore, making colorectal cancer screening a quality measure ensures that most doctors will not discuss individual risks vs. benefits and will, by default, perform screening to meet the quality measure. Essentially, people are no longer given the opportunity for informed consent. This has a bigger impact on doctors who treat immigrant populations and their colorectal cancer screening performance rates.

Imagine immigrating to Japan at age 50, going to a PCP for an Annual Physical, and being told that you need to undergo upper endoscopy every 2-3 years for stomach cancer screening!10

Over-Screening for Colorectal Cancer

The look-back period for someone with a prior colonoscopy to meet the colorectal cancer screening quality measure is 9 years. Many people change doctors, insurance, and/or move to different cities or states. In practice, this makes it challenging to find old colonoscopy reports to prove that the person underwent colon cancer screening.

Generally, most doctors will not order a screening test if the patient informs them that they underwent colon cancer screening within a reasonable time frame. However, if insurance companies (especially Medicare Advantage plans) don’t have the data, they often mail patients a free Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT). Most people don’t possess health literacy and assume that the FIT test will decrease their risk of dying from colon cancer. They will collect and submit the stool sample for the FIT test to the health plan, increasing the health plans’ quality score. FIT tests have very high false positives, leading to unnecessary colonoscopies with a risk of harm, but MA plans still reap higher profits from CMS as they meet the quality target.

This workflow is another example of Charles Perrow’s theory of “Normal Accidents,”11 which I discussed in a prior article, “The Quality of Quality Measurement.”

Resource Allocation & Access to Care

The limited availability of gastroenterologists and colonoscopy suites reduces access to these resources for individuals experiencing symptoms and require diagnostic colonoscopy or endoscopy. Furthermore, health systems in a Value-Based Care contract with significant dollars at risk may prioritize or over-allocate resources to colonoscopy for screening at the expense of diagnostic services. This will result in delays in diagnosing and treating gastrointestinal diseases, including colorectal cancer. For example, in Connecticut, it often takes several months to secure an appointment with a GI specialist.

False Assurance

Aggressive cancers often grow and spread rapidly. Individuals who develop new colorectal symptoms may be reluctant to undergo another colonoscopy if they recently had one for screening. Similarly, many doctors might hesitate to recommend a repeat colonoscopy, which can be further complicated by challenges in obtaining insurance approval. This reluctance can create a bias, potentially leading to false reassurance and delays in diagnosing colorectal cancer.

At the Intersection of Assumption, Advertising & Quality

Many people are unaware of the true risks and benefits of colon cancer screening and often believe it unequivocally saves lives.12 Aggressive advertising from large health organizations reinforces this misconception. This is further compounded by making colon cancer screening a quality measure, which disincentivizes doctors to fully inform patients about the potential risks of screening—as patients who decline colon cancer screening will negatively impact the physician's performance metrics, penalize them in value-based contracts and increase their malpractice risk. This leads to overscreening and, most likely, harm in the long term.

Improving Performance on Colorectal Cancer Screening Quality Measure

CMS has recently switched to electronic Clinical Quality Measures (eCQM) for reporting on colorectal cancer screening quality measures. My understanding is that eCQMs apply to MIPS, Medicare ACO, and Medicare Advantage Plans. Commercial Insurance plans may have more leeway in how they accept data. There are still many unknowns (to me) on how these eCQMs will work when it is time to submit data for the 2025 measurement year.

CPT-I and ICD-10 Codes

The three most common tests in use today are FIT, stool-DNA, and colonoscopy. The CPT codes for these tests are either billed by the lab performing FIT or stool-DNA tests or by the gastroenterologist performing colonoscopy. (Yet, PCP is held liable if these entities send out an incorrect bill.)

The only option here is to send the person for the appropriate screening test, and hope the bill is correct and insurance does not deny the claim.

In order to qualify for the denominator exclusion, doctors (e.g., PCP, oncologist, or surgeon) must bill using appropriate CPT and ICD-10 codes during an office visit in the measurement year (e.g., colorectal cancer, history of colectomy).

CPT-II Codes

CPT-II codes will no longer be accepted under the eCQM logic.

Supplemental Data Submission

Supplemental data is submitted in 2 ways:

Excel or CSV files with the discrete lab value (for FIT or s-DNA), if available, in the format specified by each payor.

Manual collection and submission of lab and/or colonoscopy reports.

This involves tracking down old colonoscopy reports from up to 9 years ago!

Manually collecting and submitting denominator exceptions is a mess, with every plan creating its own rules on what it will/will not accept.

Artificial Intelligence can help find the supplemental data and collate it for submission to the insurance company. However, this benefits larger organizations with a single EHR at the expense of small PCP practices.

Conclusion

Given the information that I described above, we are left with the following:

Colorectal cancer screening probably does not work in average risk and may cause harm in low risk.

Most people believe in colorectal cancer screening and want it.

I think most of you will agree with me that colon cancer screening should be an informed choice by the patient. And a quality measure is not the way to do it.

Up Next

In the following article, I will dissect the breast cancer screening guidelines and quality measure—a topic that has entered the realm of folklore rather than science.

US Preventive Services Task Force, Davidson, K. W., Barry, M. J., Mangione, C. M., Cabana, M., Caughey, A. B., Davis, E. M., Donahue, K. E., Doubeni, C. A., Krist, A. H., Kubik, M., Li, L., Ogedegbe, G., Owens, D. K., Pbert, L., Silverstein, M., Stevermer, J., Tseng, C.-W., & Wong, J. B. (2021). Screening for Colorectal Cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA, 325(19), 1965. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.6238

The biggest reason for false positives is blood in the stool due to hemorrhoids. Newer FIT tests are more sensitive in picking up even smaller amounts of blood in stool.

Swartz, A. W., Eberth, J. M., Josey, M. J., & Strayer, S. M. (2017). Reanalysis of All-Cause Mortality in the U.S. Preventative Services Task Force 2016 Evidence Report on Colorectal Cancer Screening. Annals of Internal Medicine, 167(8), 602–603. https://doi.org/10.7326/M17-0859

The PLCO trial evaluated two rounds of sigmoidoscopy.

Gohagan, J. K., Prorok, P. C., Hayes, R. B., Kramer, B. S., & Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian Cancer Screening Trial Project Team. (2000). The Prostate, Lung, Colorectal and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial of the National Cancer Institute: History, organization, and status. Controlled Clinical Trials, 21(6 Suppl), 251S-272S. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0197-2456(00)00097-0

Lewis, J. D., & Asch, D. A. (1999). Barriers to office-based screening sigmoidoscopy: Does reimbursement cover costs? Annals of Internal Medicine, 130(6), 525–530. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00017

Bretthauer, M., Løberg, M., Wieszczy, P., Kalager, M., Emilsson, L., Garborg, K., Rupinski, M., Dekker, E., Spaander, M., Bugajski, M., Holme, Ø., Zauber, A. G., Pilonis, N. D., Mroz, A., Kuipers, E. J., Shi, J., Hernán, M. A., Adami, H.-O., Regula, J., … Kaminski, M. F. (2022). Effect of Colonoscopy Screening on Risks of Colorectal Cancer and Related Death. New England Journal of Medicine. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2208375

Berg, D. M. N. van den, Lima, P. N. de, Knudsen, A. B., Rutter, C. M., Weinberg, D., Lansdorp-Vogelaar, I., Zauber, A. G., Hahn, A. I., Escudero, F. A., Maerzluft, C. E., Katsara, A., Kuntz, K. M., John, M. I., Collier, N., Ozik, J., Duuren, L. A. van, Puttelaar, R. van den, Harlass, M., Seguin, C. L., … Jonge, L. de. (2023). NordICC Trial Results in Line With Expected Colorectal Cancer Mortality Reduction After Colonoscopy: A Modeling Study. Gastroenterology, 165(4), 1077-1079.e2. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.gastro.2023.06.035

Powell, K., & Prasad, V. (2023). Interpreting the results from the first randomised controlled trial of colonoscopy: Does it save lives? BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine, 28(5), 306–308. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2022-112155

Halpern, M. T., Liu, B., Lowy, D. R., Gupta, S., Croswell, J. M., & Doria-Rose, V. P. (2024). The Annual Cost of Cancer Screening in the United States. Annals of Internal Medicine, 177(9), 1170–1178. https://doi.org/10.7326/M24-0375

Hamashima, C. & Systematic Review Group and Guideline Development Group for Gastric Cancer Screening Guidelines. (2018). Update version of the Japanese Guidelines for Gastric Cancer Screening. Japanese Journal of Clinical Oncology, 48(7), 673–683. https://doi.org/10.1093/jjco/hyy077

Perrow, C. (1999). Normal Accidents: Living with High Risk Technologies - Updated Edition (REV-Revised). Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt7srgf

Scherer, L. D., Valentine, K. D., Patel, N., Baker, S. G., & Fagerlin, A. (2019). A bias for action in cancer screening? Journal of Experimental Psychology. Applied, 25(2), 149–161. https://doi.org/10.1037/xap0000177

Hey Doc! Love your write ups. Extremely informative.